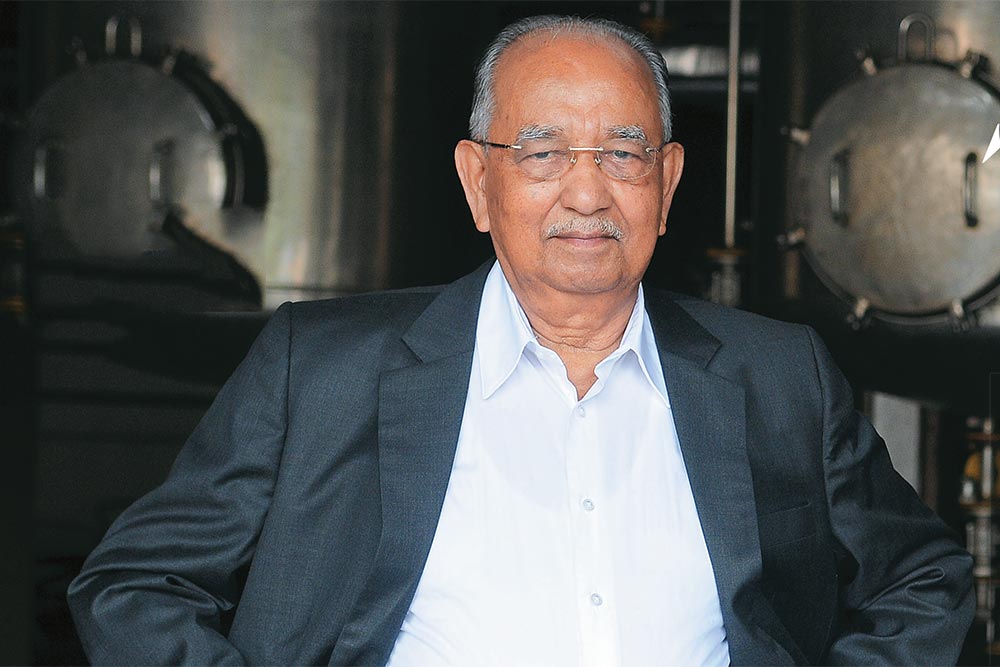

The city of Korla, in China’s central Xinjiang province, was at one time an important stop on the ancient Silk Route. The region, bordering Pakistan, is now known for its fragrant pears that are exported worldwide, and is home to extensive paprika farming. A little-known Indian company made news last year, when it set up shop here. In one move, the Kolenchery, Kerala-based Synthite made the leap from a regional player to a global one. The move was crucial for the ₹1,002-crore maker of oleoresins — flavour extracts of ground spices and herbs that contain essential oils and resin. “The region is the top producer of paprika in the country, which is an important raw material for us,” says Synthite’s chairman CV Jacob.

Indian oleoresin manufacturers account for 60% of the global oleoresins trade. One third of this comes from an oleoresin derived from paprika. The Xinjiang expansion gives Synthite a leg up in sourcing high quality paprika at better prices, and tapping the China market. This has catapulted the firm into a new league, and its strategy is now the subject of an ISB and Harvard Business School case study.

Synthite’s journey began in 1972 from Kolenchery, Jacob’s hometown in Kerala’s Ernakulam district. Around that time, the Central Food Technological Research Institute (CFTRI) in Mysore had developed a method for isolating active ingredients in spices using steam distillation and solvent extraction processes. This held the promise of opening up new markets for Kerala’s abundant produce of cardamom and black pepper. “It seemed like a tremendous opportunity in the making,” recalls Jacob, who started Synthite with ₹10 lakh of his savings, and a ₹30-lakh loan from Union Bank of India.

The formative years were bumpy. The CFTRI technology was primitive, with limited applications for commercial use. Jacob and his R&D team worked to improve upon it, but seasoning and flavouring companies in the US and Europe were not convinced about Synthite’s ability to manufacture quality products and deliver them on time. It took four years of persistent product development before Synthite’s products got established in the business. Today, it has five processing and extraction units in India and one in China, plus an additional unit for the spice business with a total capacity of 15,000 tonne.

Among Synthite’s key overseas customers are seasoning and flavouring firms like Givaudan, IFF, Griffith Laboratories and Kerry Group companies based in the US, UK and Germany are large buyers, but with saturation in these markets, the action has been shifting to China, Indonesia and Vietnam.

Unlocking flavours

Synthite has two oleoresin divisions — bio ingredients and spices. Its five bio ingredient units with a combined capacity of 275 tonne a day, convert raw spices (chilli, pepper, turmeric, cardamom) into oleoresins. These are supplied to flavouring and seasoning firms and they, in turn, sell seasonings and flavourings to food processing companies. Synthite has three institutional brands in the bio ingredients space — Eezee Spice, Necol and Neox — and one consumer brand, Natxtra.

At its spice division, which came up in 2006, spices are crushed and granulated and then steam-sterilised for supply to seasoning companies, — including Synthite’s subsidiary Symega, which sources 30% of its requirements from the parent — hotels, catering businesses and large canteens. Its premier brand here is Kitchen Threshers, which along with Natxtra, is sold in the consumer market.

Spice-based oleoresins give a uniform flavour and aroma and are used in food products such as processed meat, noodles, beverages, sauces, canned meat, soup powders, and confectionery items. India accounts for 50% of the world oleoresin output of 18,000 tonne. Synthite is the big daddy here, accounting for 48% of India’s oleoresin exports and 25% of global trade in the product. The next big four of the industry are Kancor Ingredients, Plant Lipids, a breakaway from Synthite run by one of Jacob’s nephews (both in Kochi), Kalsec Natural Ingredients and Naturex, both foreign players. Worldwide, the top 10 companies account for 80% of the market.

A bulk of Synthite’s sales come from exports to the US, Europe and the Far East, where the processed food business is well developed. “Synthite has invested heavily in R&D and process and product development and this has helped it bring down the cost of the products it sells,” says Giridhar Rao, director, global spice network, at Griffith Laboratories, an international seasoning company, which is also a customer of Synthite. In 2006, Synthite entered into a JV with Austria-based Omega Food Technology to form the ₹67.1-crore Symega Savoury Technology.

Symega makes seasonings and savoury ingredients that are used in snack foods, processed cheese, convenience foods and processed meats. And to gain a foothold in the confectionery flavouring segment, Synthite entered into a 50:50 JV with Aromco of the UK in 1997, making products for the bakery, beverage, confectionery, dairy, pharma and food processing sectors, including names like Nestlé and HUL. However, it plans to buy out Aromco’s 50% shareholding in the Indian venture by October 2013, since the UK parent has been acquired by an Israeli company.

New recipe

All along, Synthite’s main challenge has been professionalising its management as it scales up operations. Jacob informs that apart from inducting professionals into leadership roles, it has tied up with IIM-Ahmedabad to conduct leadership programs for its mid- and senior-level executives. The most unique experience so far has been setting up Synthite (Xinjiang) Biotech, the new Chinese entity. Language was, of course, a stiff cultural barrier. Finding a place to set up the office proved even more difficult — until the local municipal body helpfully vacated its 1,000 sq ft office, providing Synthite

with free electricity, telephone and wi-fi connections.

The new work culture threw up some unique challenges, and adapting took time. “The Chinese are extremely hierarchical, with a strong sense of loyalty,” says Jacob. In a crisis, workers there would rather listen to their Chinese manager than a more senior Indian with greater expertise. The Korla unit has 60 Chinese employees and only three Indians. Key managers from both countries are regularly sent on exchange programmes for technical and language training. Currently 300,000 tonne of paprika is being grown here. Synthite plans to develop its Korla facilities as a major export hub, and grow other raw materials like lavender, tomato and grapes there as well.

While 93% of Synthite’s turnover comes from its spice and bio ingredients divisions, the company has, over the years, also ventured into other areas such as hospitality, real estate, wind energy, farm technology and fragrances.

Taste results

Synthite has set a rather ambitious target of tripling its turnover to ₹ 3,000 crore by 2020. This involves increasing volume growth and adding 24,500 metric tonne of capacity along the way. Sunil Chopra, IBM distinguished professor of operations management at Kellogg Northwestern University, who co-wrote a case study on the company in March 2013, says, “The processed food industry is set to grow exponentially in emerging markets like India.” He points to the company’s operational efficiency and decentralisation in decision-making, so ideas and innovations come from all levels and are accepted. This is a big plus in Synthite’s favour going forward, he adds.

Rao of Griffith Labs also feels it is a plausible target. “Prices of spices have increased dramatically over the past 10 years. So, companies are seeing a four-fold jump in turnover without any significant volume growth. All Synthite has to do to achieve the target is double its volumes till 2020. Untapped markets in South and Central America, Africa and Asia offer it an opportunity to do so,” he says.

Raw materials make up 68% of Synthite’s costs, and Jacob plans to buy them cheaper and process them faster. Its farm technology initiative where it is able to procure higher quality raw materials through contract farming, is an advantage. Jacob also expects the combined turnover of Symega and Aromco to multiply to ₹500 crore by 2020 — currently the figure stands at #72 crore — by selling spices and value added seasonings to retail consumers.

But Synthite’s speeding juggernaut could face a few potholes before it reaches its final destination. Responding to increased demand from emerging markets will be a challenge and the company has ramped up capacity in both its bio ingredients and spice divisions. But this capacity needs to be effectively utilised. Chopra says Synthite seems to have over-invested in augmenting capacity, making its underlying cost structure higher.

And while the company is looking to enter geographies such as China, Sri Lanka and Indonesia due to their abundant supply of key raw materials, quality is not assured by mere presence, says Rao. “They will have to work closely with farmers to assure quality,” he says. “Yields are also quite low in these countries.” Rao adds that seasoning and flavouring firms in Europe are looking to continuously reduce their working capital budgets. For Synthite, selling products on credit will in turn impact its cash flows.

There are some factors going in the company’s favour too. Its new product development and research unit has been working on replacing synthetic colours with natural ones for the dairy industry. This emphasis on using natural ingredients is in line with a global shift: the US FDA and the Food Safety Standards Authority of India are both revamping their rules in favour of natural ingredients. Jacob also points to the significant growth opportunity in the size of the market. “Per capita consumption of flavourings and seasonings is $80 in the United States, $8 in Korea, Taiwan and Australia and just $1 in India and China. This can only grow in the future.”