Our family comes from a little town called Karad where my grandfather began his life in a humble manner — walking 10 miles every day to collect letters for a rich zamindar. But thanks to his entrepreneurial zeal, from a scratchy start in the early 1900s he went on to become the turmeric king of the Sangli market. However, after my grandfather died in 1954, my father closed down the trading business as it proved to be too risky and instead focused on building the sugar cooperative movement in Maharashtra.

Around the same time, in the early 1960s, the Kirloskars were running their business from Kirloskarwadi, which was 18 miles from where we lived. Since my father enjoyed a good relationship with SL Kirloskar, he encouraged my father to set up a unit that could supply forging crankshafts for engines made at their Pune plant. That’s the genesis of Bharat Forge. In 1964, my father started construction of the unit and by 1966 we began commercial production.

It was no mean feat, given that my father did not have a legacy of riches. Our only family asset back then was a 40-acre sugarcane field that yielded a profit of about Rs.1 lakh in a good year. My father invested his entire savings of Rs.5 lakh towards the share capital of the company and got two or three acquaintances to put in equivalent sums. He raised the balance capital from small farmers across the sugarcane belt of Maharashtra, some of whom are still shareholders in Bharat Forge.

Taking over

When I joined the company in 1972, we were clocking a turnover of Rs.3.75 crore but the company was loss-making. I turned around the business by just being on the shop floor and being hands-on, taking multiple decisions at every level. Forging machines are self-destructive by nature as they are run under harsh conditions, which is why you need a high level of technical discipline. That does not come unless you get the technology right, improve technical processes and constantly train people. By the beginning of the 1980s, we were a relatively stable and strong organisation.

Though the forgings industry was as nascent as the automotive industry, in those days there were close to 30 forging companies, including MNCs such as a British company called GKN in Kolkata, and US-based Wyman Gordon Forgings, which operated out of Mumbai. By the 1980s we had surpassed them in size because we became technically smarter and faster in our ability to work. While we used to compete on similar cost structure, we were preferred suppliers because we were nimble-footed in meeting our client demands by customising products to suit their needs.

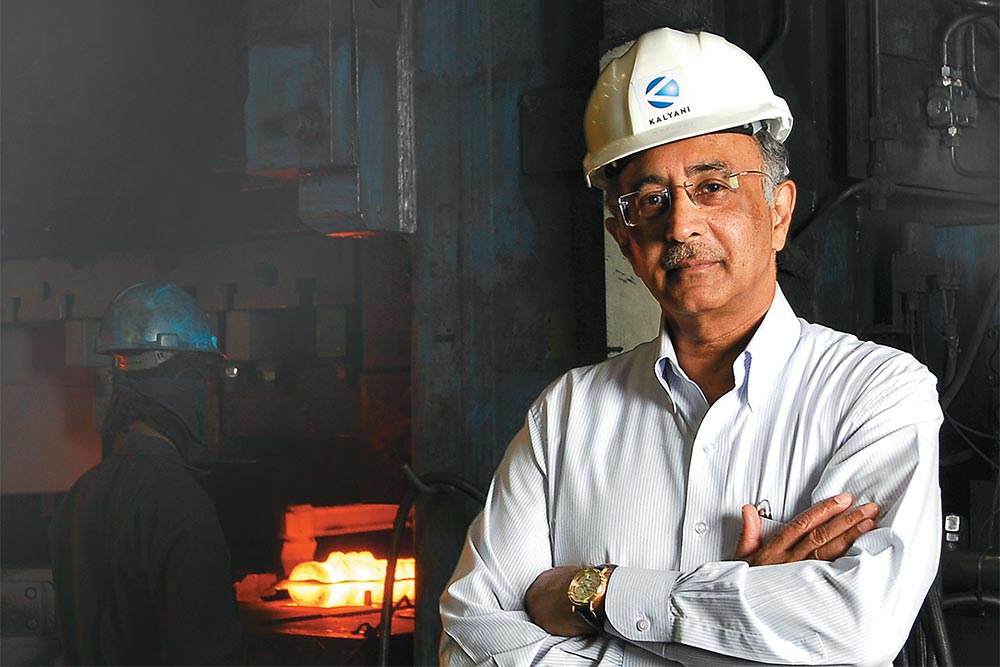

But our biggest problem those days was getting good quality steel since there were only two suppliers — Visvesvaraya Iron and Steel Plant and an alloy steel plant in Durgapur, both of which are now part of SAIL. We were not getting the right quality, so my idea was to set up a steel alloy plant. In 1974, the government came out with a policy allowing private industry to set up steel units, provided the investment in plant and equipment was under Rs.1 crore. We decided to go ahead and in 1975 our first steel alloy plant, Kalyani Steel, was born right here in Pune. Here again we managed the whole technology part on our own.

In the 1980s we looked at the value addition, as a whole new generation of trucks was coming up and so was Maruti. So, we got into the brake line business for passenger vehicles and driveline and axles for trucks. All these required forgings and, hence, it was a value addition for Bharat Forge. But getting the technology was a big challenge. It took a lot of effort and time convincing our tech partners (Bendix for brake line and Rockwell International for trucks) to come to India, but the biggest challenge was getting past their legal department! Tech transfer contracts are a lot simpler today than they were back then.

While the axles business is still part of the group, we sold off Kalyani Brakes as passenger vehicle technologies began changing and nobody would part with their technology unless you gave them a majority stake in the business. For us, it didn’t make sense to stay on as a minority partner, so we sold out to Bosch in the 1990s.

In fact, the early years of liberalisation were not exactly a purple streak for the company as it was facing a sluggish domestic market. It was around this time we felt that unless we modernised and went in for exports, there was no way to survive. At that time, people didn’t believe we would be successful; the industry and markets were both critical of our strategy terming us a “white elephant”. It was a time when the belief was Indians could not create technology and that relying on technical support from advanced nations was the only way to succeed. But I believed that creating your own technology was a better option because relying on partners would have meant restrictions on doing business in markets where they were present.

Through borrowings, we invested a large amount (Rs.140 crore) on modernisation. We created a facility that helped us to get orders from companies in the US and that’s how our export business started scaling up in the 1990s. What gave us the confidence was that whatever we had achieved was on the basis of our technological strength and not an outcome of labour arbitrage.

Sprint to the top

Because of our success in exports we said, why not look at being among the top five forging companies in the world? In 2000, we just had four-five export customers. The big question was, how do we get a crack at the Daimlers, GMs and Fords of the world? That’s when we created a strategy of externalising ourselves, beginning with our first buyout of a small company (Dana Kirkstall) in the UK in 2000 for a relatively small amount. The buyout gave us a multi-million dollar order-book. But more importantly, from four customers we got an additional 10 European OEMs.

That fired us up to take larger bets in Europe. Soon we had four companies under our belt. It was a clear strategy to position ourself as a preferred supplier across markets. Since we were completely absent in the high-performance cars segment, we made our acquisition in Germany by buying Carl Dan Pedinghaus, which was in the bankruptcy court. Our next buyout was Imatra Kilsta, a forgings company in Sweden, after which we bought a company in the US and later entered China through a joint venture with FAW Corporation. The idea was to create a worldwide footprint and between 2000 and 2008, we did manage that and grew 10-fold.

However, 2008 changed the world for manufacturing companies dramatically. It was especially traumatic for the US auto industry, which went into bankruptcy. It was difficult to predict what could have happened. I was in Peoria, Illinois, when the financial crisis hit in late 2008 and I saw Caterpillar’s sales fall 75% in one month: such was the impact on the manufacturing industry. It was a difficult patch for us and we, too, had to quickly downsize operations.

But what helped our cause was that most EU companies had seen such events in the past. So, there was no question of non-acceptance from the labour force as they realised that we weren’t any different from others who were going through similar pain. Today, all our buyouts are profitable, barring North America. But the problem here is that analysts don’t understand that in Europe you have a certain cost structure. Suppliers in Europe make 7-8% EBITDA margin and in India Bharat Forge is doing 25%. So, they expect you to make similar numbers in the EU… you have to see the financial numbers of other EU companies to understand the reality.

But we are happy that our acquisitions have helped develop a link between Indian manufacturing and overseas customers. We were unable to convince large OEMs that as an Indian company we could supply critical equipment to them on an on-going basis. So, we had to own these entities and the rub-off effect is that we have increased exports from Bharat Forge as well. Today, there is not one auto component supplier who has a client list like ours (Daimler, BMW, Audi, Volkswagen and Volvo, to name a few) or even the export content that we have.

The reason is simple — they don’t have a strategy that allows them to do this. We invested about €100 million (Rs.600-odd crore) on our acquisitions, which every year generate a cash flow of Rs.60-70 crore. Our only unfortunate experience is in the US, which we would term as bad luck as the entire auto industry in that country went down. That’s life… everything may not work out as per your plans.

But the key factor that differentiates us is the kind of sophisticated labour force that we have today. When we began modernising in early 1991, the first thing that hit us was that nobody in the plant was equipped enough to handle automation. The first six months was a complete failure as nobody understood robotics and we realised that we needed a different HR model. In the 1990s, our 3,000-odd workforce was largely (2,500) blue-collared and the rest was managerial.

Today, it’s the other way around: we have over 2,000 engineers. While most workers opted for VRS, others were trained on campus in our engineering college, exclusively for the company. We have 45 seats every year and 600 applicants! It’s free for employees and is run by BITS Pilani. The kicker is that you get a BITS degree, which motivates you to do well. That’s why we call it our internal talent factory.

While I am not a major votary of business management, my philosophy is that if ‘’you” have a vision, it has to become “everyone’s” vision and that’s what leadership is all about. Secondly, empower people in the real sense of the term by allowing them to implement good ideas and, more importantly, give credit where it’s due. That instills a sense of pride and belonging. We had a vision to be among the top five global companies, but today we are the largest forgings company in the world. It’s a tough act to follow but then that’s what challenges are all about — if there risks are aplenty, there are rewards galore, too.