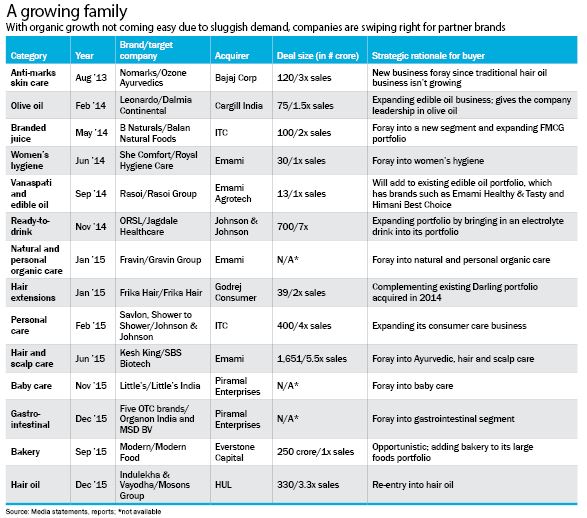

Very often, carefully named concepts fail to live up to their own once-suitable monikers down the years. A case in point would be the domestic fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector, which has seen an unprecedented slowdown in recent years, right down to a big dip in demand. Of course, this is not something that Bajaj Corp MD Sumit Malhotra has witnessed for the first time in his 30-year career. “We have seen several periods of low demand offtake in the past as well, but never for more than two quarters at a stretch. This time around, it has lasted nine quarters,” he says. Although 2015 has not been an easy year for Indian industry in general, what with the disappointing rainfall and slow growth, FMCG companies seem to be more than a little worse for wear. And their attempts to firefight this situation are clear — a majority are slashing prices or increasing their advertising spend, and some have even taken the risky decision of expanding through acquisitions. Given that sales are growing at their slowest pace in 13 quarters, Malhotra says he is only too nervous thinking about how long this period will last. Given that he handles the Rs.857-crore Bajaj Corp, a key player in the light hair oil business, Malhotra says he is hoping that “consumers start spending, which is the only thing that will make a difference.” He has a point: for the third quarter of FY16, the hair oil industry has grown by just 0.7% compared with a 6% growth in 2014-15. As companies head to the market to make their picks for inorganic growth, a lot of serious money is being spent on brand acquisitions, which are mostly in categories new to acquirers. The hope, of course, continues to be that one of these buys plays out, and in a big way. But are the companies biting off more than they can chew?

The best acquisition targets, of course, are brands operating in niche categories, since these tend to be strong in a particular market or segment. Historically, these are the kind of companies that have demonstrated high growth rates. Since both buyers and sellers are acutely aware of the fact that larger companies have found the acquisition game slippery and that big-ticket brands are in short supply, buyers are willing to do almost anything to convey their interest. In fact, the reality is that many expensive buyouts in the FMCG sector have come a cropper in the past. But despite the desperation in the air — or rather, because of it — there is a marked difference between the acquisitions made in the recent past, as compared with those in 2011-12.

According to Abhishek Khosla, vice-president, MAPE Advisory Group, the domestic story back then was characterised by high-profile deals such as Reckitt Benckiser acquiring Paras Pharma’s portfolio, the buyout of Wockhardt’s nutrition business by Danone or Jyothy Laboratories taking over Henkel India’s brands. “However, over the past two to three years, the focus of both domestic majors and MNCs has been on filling product or brand gaps — for instance, HUL acquiring Indulekha Bringha Hair Oil or ITC buying Savlon — instead of making a diversified play or just boosting distribution,” Khosla points out. Besides, there have been very few outbound deals by domestic players. “The interest here has diminished and most companies have focused on managing existing businesses and exploiting domestic opportunities,” he adds.

The tough get going

Take the case of Piramal Enterprises, which owns brands such as Saridon, Lacto Calamine, i-pill, Jungle Magic and Caladryl. “We look at ourselves as a player in the self-care market, positioned between pharmaceuticals and FMCGs. Our strength is our distribution reach — nearly four lakh chemists — and any brand acquisition will play to that,” says Kedar Rajadnye, the company’s COO, consumer products division. Two of the company’s most recent buyouts have been about filling the gaps in its portfolio. Piramal’s expertise in this business comes in no small measure from the fact that the group ran a successful domestic formulations business before selling it in mid-2010 to Abbott for $3.72 billion.

In November 2015, Piramal Enterprises bought out Little’s India, a babycare brand, for Rs.73 crore. This was in part so that the company could reach out to the 0-4 age group, since Piramal’s Jungle Magic brand only caters to the 5-10 age group. “There was an opportunity to build a babycare range in the absence of a player with a national presence. Again, we are looking at ways to exploit our large chemist network,” explains Rajadnye. He says the reason for taking the inorganic route for expansion was the company’s limited success with new product launches. “Today, the success rate in the sector is less than 15%. Besides, the cost of launching a product has at least doubled over the past three years, which makes the process extremely difficult,” he adds.

At Piramal, the portfolio-building process is not limited to the babycare segment. The company saw another sliver of opportunity in the domestic self-care market, which is worth Rs.14,000 crore in size and is growing at 13-14% each year, with the biggest players being Reckitt, Dabur and GSK. Given that barely 30% of the market is addressed, the trick here is to constantly look at products for new growth areas. A month after the Little’s deal, Piramal Enterprises bought five over-the-counter (OTC) brands from Merck for Rs.92 crore. “Our portfolio had a gap in the gastrointestinal segment and that is why we went for the deal,” says Rajadnye. He adds that the reasons behind such buyouts are not purely financial. “Some brands provide a strategic opening and one may have to pay a higher price for that opportunity. The way we look at it, each acquisition should provide a higher return than the cost of capital and the opportunity cost for that capital.” Former Marico CFO, Milind Sarwate, who founded his own consultancy Increate Value Advisors, offers another perspective. “What we are seeing today is no different from the gold rush.” According to him, the slowdown in the sector is more about smaller and regional players eating into the market share of larger players.

“Two years ago, a company like Patanjali did not even exist. New players are basically trying to expand the periphery of the consumer universe.” In a scenario like this, larger players have little option but to acquire these small-but-strong players, even if it comes at a high cost. “Large players realise that building a brand is a competitive exercise. In most product categories, the opportunity is in the potential move from the unbranded to branded segment,” Sarwate adds. Malhotra himself admits to taking a look at at least eight buyout opportunities each year in the domestic market and over 20 from outside India. “Apart from helping you grow faster and adding an existing brand to your portfolio, acquisitions ensure that you do not have to start from scratch,” he says.

Fishing for gold

In mid-2013, Bajaj Corp acquired the Nomarks anti-marks skincare brand, the first time ever that the company took the inorganic route. At a price tag of Rs.120 crore, industry trackers say the deal was struck at 3x sales. If you thought Nomarks was far removed from the light hair oil segment that Bajaj Corp has historically been present in, Malhotra has a valid defence, pointing out that hair oil has a 92% penetration in India, leaving no scope for growth. “We wanted to look at a segment that was underpenetrated and offered high margins. Low levels of usage in the anti-marks skincare business seemed like a big opportunity,” he adds. For any acquisition in the FMCG industry, the thumb rule for payback, according to Malhotra, is seven to eight years. The decision to take the inorganic route, in fact, was made as far back as 2009. “We came very close to two buyouts; those brands have still not been acquired,” he smiles. Sarwate points out that the RoCE for an FMCG buyout needs to be at least 40% for it to work out. He refers to Emami’s buyout of hair and scalp care company Kesh King in June 2015, which at that RoCE would call for a profit before tax of around Rs.700 crore. “That means Kesh King would need to clock an operating profit of Rs.900 crore and sales of at least Rs.2,500 crore,” he explains. From today’s sales figure of Rs.300 crore, that is a very long way to go (Emami paid Rs.1,651 crore for the brand).

“In a stormy sector like FMCG, it is very difficult to deliver on a high-cost acquisition. The fact is that at least half the buyouts in this sector do not work out,” Sarwate insists. On the issue of valuation, Harsh Agarwal, director, Emami, insists, “The reality of the situation is that nothing comes cheap today. The supply of good assets is limited and the demand for them continues to soar. But Kesh King offers high margins (reportedly 80% at the gross level) and that is why we are convinced about its potential,” he says. According to him, the environment has been challenging for at least a year now. “We are banking on growth taking off this year and that is why we have made this acquisition. Only inorganic growth can replace the need for organic growth. And that approach comes at a price. For us, however, a strategic fit is more important. We were already in the hair oil business with Navratna Oil, which is why Kesh King was a good fit.” He thinks there is enough scope for growth in the segment and that customer acquisition won’t be challenging.

That confidence is not necessarily backed by the numbers, however. In November 2015, less than six months after the Kesh King buyout, the Emami management revealed to the public that seller SBS Biotech had under-reported inventory levels. This fact was not disclosed at the time of the deal and raised serious questions about the due diligence carried out.

But it is not just in India that FMCG majors have looked for greener pastures. Godrej Consumer Products, acquired Frika, a hair extension brand that sells synthetic weaves, wigs and braids, early last year. This was preceded by the purchase of a majority stake in Darling Group Holdings, a company that sold hair extension products in 14 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, in mid-2011. “The Frika deal gives us a broader portfolio of offerings and reaches more market segments. The company has more premium offerings and a stronger presence in the western cape region of South Africa, where Darling has a smaller presence,” says Adi Godrej, chairman, Godrej Group. While he admits that it could have been possible for Darling to expand its portfolio to meet Frika’s product reach, it would have taken a while. “Therefore, an acquisition where the company had complementary strengths enabled us to meet our objectives faster.”

Seller’s market

The sellers, on their part, are having a field day, what with valuations hitting stratospheric levels. For instance, at Rs.1,651 crore, Emami’s Kesh King buyout came at a whopping 5.5x the brand’s sales. Then there is Girish Patel, founder, Paras Pharma, who sold his company to Reckitt Benckiser in late 2010 for a big sum of Rs.3,260 crore. For the buyer, it was a chance to acquire successful OTC brands such as Moov, Krack, Dermicool, Set Wet and Itchguard. Given that the first three today are growing at just 10% per annum, it is difficult to justify their valuation of over 8x sales, which enabled Patel to and make a huge profit on his 30% holding. Today, he talks about having considered getting his company listed. “I would have liked that, but with just a 30% holding, it was always going to be more than a little difficult,” he explains. As much as 63% of Paras was held by private equity major Actis, which had invested in the company in 2006. This deal yielded a profit of at least 3x. “Actis was at the end of the investment cycle and this was a very good opportunity to exit. Besides, it was looking to raise its next fund and Paras was a showcase investment the fund could speak of,” says Patel.

In his modest office in Mumbai’s business district of Nariman Point, Darshan Deora says the decision to sell his brand, Little’s, was one that was both emotional and economic. “We owned this brand since 1980 and had put a lot of effort into it. At the time when we decided to sell, we had a presence in 25,000 outlets, compared with Piramal’s 4 lakh outlets,” he says. According to him, replicating Piramal’s distribution was “next to impossible”. As a brand, Little’s, says Deora, grew at a CAGR of 30% over the past decade. “There is no doubt that the brand has a lot of potential and babycare is still a very nascent industry. The brand was important and it fits nicely into the Piramal portfolio,” he maintains. Of course, the temptation of a high valuation is hard to resist, although most sellers fail to admit this. “Brands cashing out today is the result of high valuations and nothing else. In the process, the market scenario has become quite difficult to navigate, although growth is not an issue,” says Harsh Mariwala, chairman, Marico.

Buyer beware

That’s not always true, though: growth has become a problem with several brands. One-and-a-half years after Reckitt acquired Paras, the company disposed of the personal care category in the portfolio — Livon, Set Wet and Zatak — to Marico for Rs.600 crore, or 4x sales. And Marico itself has not had it easy with serums (Livon) and hair gels (Set Wet), with the market size for each being not more than Rs.300 crore. The real concern has been the deodorants category, where Set Wet and Zatak operate, with Fogg being the biggest disruptor. Launched in 2011 by Vini Cosmetics and positioned as a long-lasting deodorant, this brand has notched up a market share of 17%, with ITC brand Engage taking the second position. Consequently, HUL brand Axe is now third in the pecking order, from its erstwhile No.1 spot. “Competition in this segment was much higher than what we anticipated at the time of the buyout,” concedes Mariwala. Today, Marico with its two brands has a market share of barely 5% in the deodorants market.

A change in market dynamics can, then, prove to be extremely detrimental to a brand, especially when it changes hands. Prateek Srivastava, co-founder, ChapterFive Brand Solutions, a brand consultancy, points to certain symptoms that show up when a brand owner is bracing for an exit. “The owner will then start milking the brand and one will see a lot of consumer promotions, launch of smaller SKUs and massive ad spend. The clear objective is to increase the top line at any cost,” he says. Srivastava cites the instances of Moov, a brand owned by Paras Pharma, which launched smaller pack sizes, or Set Wet, which entered the deodorants market from its primary hair gel business. “This causes significant damage to the brand and its equity gets diluted very quickly. By the time the buyer steps in, too much has already taken place with the brand.”

HUL’s acquisition of Modern Foods was a waste of both time and money. It finally sold the company to Everstone Capital for Rs.250 crore at a multiple of 1x sales. HUL had struggled with Modern from the time it bought it from the government in 2000. Modern, whose portfolio was mostly focused on bread, faced stiff competition from local players and was unable to derive synergies from its own distribution system. “Often, large companies like HUL find it difficult to deal with a small brand and Modern is just a case in point. It just did not fit into HUL’s portfolio,” says Srivastava.

Mariwala says that it is better to buy “strong brands for a higher price instead of buying weak brands just because they are affordable.” He says companies need to be clear about why they are acquiring brands — is it for technology, distribution or market share? “If a buyout can strongly justify any of these, a high valuation may still be worth it.” A case in point is Nihar, which Marico acquired from HUL in 2006 at 2x sales. While competition considered hair oil a dying business, Mariwala says he persisted because there was a ‘geographical need’ in the segment in east India and he wanted only the brand, keeping his strategy asset-light. That bet has paid off, with the brand bringing in Rs.500 crore combined.

These kinds of acquisitions, however, are few and far between. But despite being a costly affair, acquisitions in the consumer space are unlikely to die because the purpose is not just to augment growth prospects, but also about keeping smaller, nimble-footed players from becoming bigger threats in the future. When it’s a question of protecting your home turf, price is not something companies care about too much. After all, who cares if they make a little less profit in future?