By Payal Seth and Palakh Jain

The Shadow Pandemic Of Corruption And Its Impact On The Healthcare Delivery

Corruption in healthcare became even more relevant during COVID-19 as embezzlement of health care funds, using expired vaccines, fraudulent health contracts, etc have life-or-death consequences

Corruption is defined as dishonesty or criminal offence undertaken by a public official or organisation, who have been entrusted in the position of authority, to attain illicit benefits for their personal gain. Corruption in healthcare became even more relevant during COVID-19 as embezzlement of health care funds, using expired vaccines, fraudulent health contracts, etc have life-or-death consequences. It would not be inaccurate to term COVID-19 as a corruption pandemic as citizens across the globe have reported a widespread rise in corruption post-pandemic (Transparency International, 2020a). It is in this context that we discuss the heterogeneity in healthcare response to the pandemic in the light of varying levels of corruption across the nations.

Our oped analyses corruption through two channels: first, corruption has been shown to alter the spending structure of the governments through siphoning off the funds from education, health and social services to rent seeking sectors like fuel and energy, defence, public services, etc. In terms of corruption, these are the sectors that have a higher scope for rent seeking. The second channel through which corruption might impact the COVID-19 health care protocol is by undermining the institution of democracy. For example, budget transparency in public health spending is the key to handling the emergency response during a global pandemic and this becomes difficult to enforce in the presence of corruption. More corrupt nations might disrupt parliamentary proceedings that might be analysing the government’s measures or impose bans on the freedom of the press.

We use the corruption perception index (CPI) 2020 from Transparency International. The score ranges from 0 to 100 (with 0 being most corrupt and 100 as highly clean). We also use the world bank statistics for the public sector spending on healthcare as a percentage of GDP (2019, the latest available). To measure the changes in democratic institutions, we use information from Pandemic Backsliding Project by the University of Gothenburg. Specifically, we use the Pandemic Democratic Violations Index (PanDem Score). This dataset tracks the extent to which the government’s responses during the pandemic violated democracy between March- December 2020. The score ranges from 0 to 1; with 0 capturing the least violations of democracy and 1 as the most violations.

We explore the cross-country association between the CPI score and public sector health spending, and second, the CPI score and the PanDem Score. I describe instances from across the world elaborating on the association.

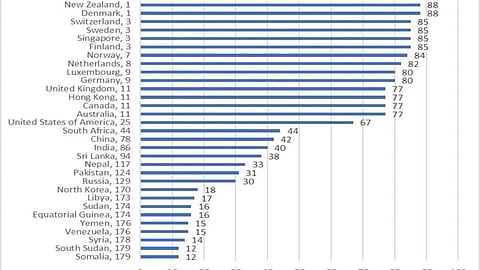

CPI Descriptives

Denmark and New Zealand shared the first rank in 2020 with a CPI score of 88. These countries were followed by Switzerland, Sweden, Singapore, Finland, Norway, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany, United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Canada and Australia. The USA and South Africa were ranked 25 and 44 respectively. Coming to the developing countries, China ranked 78 with a CPI score of 42 followed by India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Pakistan and Russia. The countries with the least CPI score were North Korea, Libya, Sudan, Equatorial Guinea, Yemen, Venezuela, Syria, South Sudan, and Somalia.

Association Between CPI Score and Public Health Expenditure

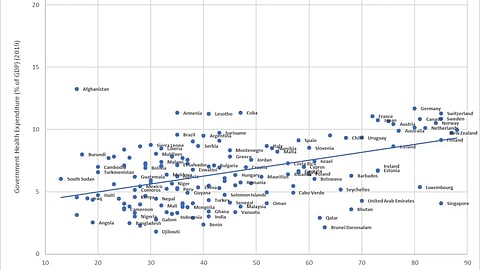

Figure 2: Cross-country association between CPI scores and public health spending for the year 2019 for 156 countries. The blue line is the fit along with the scatter plot.

Figure2 depicts that there is a positive association between the CPI score and public spending in health care (as a percentage of the GDP). This implies that the higher the CPI score or the least corrupt the country is, the more the government is spending on healthcare.

I now discuss some countries to illustrate the relationship between corruption and public health expenditure. Romania has a CPI score of 47 (a persistently more corrupt country than the other European nations) and also has a lower expenditure on health care than the average European countries. This translated to medical personnel shortages during COVID-19 (Salceanu, 2020). Moving to Uruguay, this country has a CPI score of 70 – the highest in Latin America and the government spending is also the highest among all the countries in similar regions. The country was well-prepared for a pandemic like COVID-19 with its state of the are epidemiological surveillance system (DW, 2020). Similarly coming to a low CPI score country – Bangladesh (26) – one notices that it is one of the worst performers among other countries in Asia. The government’s investment in healthcare is also abysmal relative to other Asian countries. After the pandemic, reports of misappropriation of relief aid as well as bribery in health clinics have surfaced (Lata, 2020).

Association Between CPI Score and PanDem Score

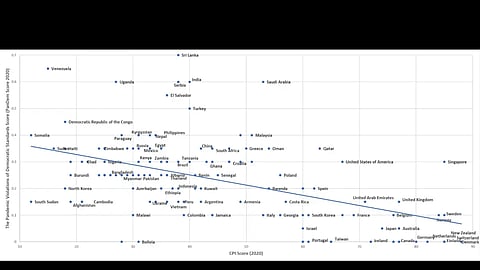

Figure 3: Cross-country association between CPI scores and the PanDem score for the year 2020 for 135 countries. The blue line is the fit along the scatter plot.

Figure 3 suggests that there is a negative association between the CPI score and the pandemic violations of democratic standards score. This implies that the more corrupt the country is the more it is likely to commit violations of the democratic code. The figure suggests that the violation of democracy occurred differently in various regions of the world. Sub-Saharan African countries were worst affected due to media censorship and the spread of misinformation. Likewise, Central Asia and Eastern Europe imposed restrictions on movement without any time limit.

I now elaborate on this relationship by focussing on some countries. Consider the United States. It has a CPI score of 67 and an uncharacteristically high PanDem score of 0.3 in 2020. The violation of the US’s long-standing pride of democratic institution occurred when corruption challenges arose regarding the oversight of the US $1 trillion package (Qing, 2020). Philippines has a CPI score of 34 and a high PanDem score of 0.4. The government’s response to the pandemic was characterised by human rights violation, a ban on the freedom of the press and abusive enforcement of lockdown measures (Human Rights Watch, 2020; Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, 2020). Moving to New Zealand, this country has a CPI score of 88 and 0 as its PanDem score. This can explain the country’s exceptional efforts undertaken during the pandemic. The government was communicative about the lockdown measures and this helped the citizens to develop trust in following the leaders (BBC News, 2020).

Through this oped, we urge the governments to undertake transparent contracts for procuring medicines and share truthful information about the pandemic in a timely manner. Further, the governments can improve access to the data from clinical trials, which will help the scientist learn from the previous limitations, instead of starting from scratch and making the same mistakes. More

importantly, the government should protect whistle-blowers to save countless lives. Finally, even though the participation of the private sector is important to expedite the recovery from the pandemic, the interests of the citizens must be protected at all costs. It is crucial to strengthen the outreach of anti-corruption institutions to ensure that the limited resources are allocated in a fair and equitable manner.

Payal Seth is a PhD Scholar and Palakh Jain is an Associate Professor at Bennett University