The year 2021 was the worst for Rajeev Roy (name changed on request). The private sector employee lost his job in Pune towards the end of 2020 after his company laid off employees to combat the economic cost of the pandemic.

Why Household Gold Is Becoming A Loan Trap

Once seen as source of financial security, families are finding it tough to release pawned jewellery from gold loan companies, which resort to auctioning. Muthoot Finance recently brought a public notice in national newspapers for auction of 33,000 gold articles. Policy watchers point out that the rush to encash domestic gold articles is symptomatic of an economy under duress.

He returned to his home state West Bengal and started looking for a job, but the deadly second wave of Covid-19 in 2021 ravaged his family. After both his parents tested positive, the medical expenses towards saving them brought the family to its knees. “Before falling sick, she (mother) made me swear that if she fell sick, her gold jewellery would be put to use,” recalls Roy.

Unfortunately none of the parents survived the deadly disease. “I had thought that losing my job was the worst thing to have happened to me. But, I was orphaned within a year. My mother’s jewellery could not save either of their lives. I am still without a job. How would I repay the loan?” he asks, choking.

Roy is not an outlier. He is part of a larger section that has added to the trend of increasing demand for gold loans due to financial stress caused by the economic situation in the country.

Data Validation of Distress

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data on sectoral deployment of bank credit shows a growing trend in loans against gold jewellery. On November 22, 2019, it was Rs 29,514 crore, which rose to Rs 33,451 crore by March 27, 2020 and stood at Rs 65,630 crore on November 19, 2021.

“In the past two years, due to many small businesses coming under stress, the demand for gold loans has been rising. A year ago, loan against gold as a product at Shriram City Union Finance was 10 per cent of our AUM (assets under management). By September 2021, it had risen to 14 per cent of our book,” Y.S. Chakravarti, MD and CEO, Shriram City Union Finance, told Outlook Business.

The distress, however, predates the pandemic. Policy watchers point out that the rush to encash domestic gold articles is symptomatic of an economy under duress and impacting different sections of society differently. The beneficiaries of a robust small and medium enterprises (SMEs) sector have been affected the most through a series of events, like demonitisation, the shock introduced by inefficient implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) and then the Covid-induced lockdowns.

“Debt is a bad thing as per the Indian ethos. Taking loan against gold is the worst, sentimentally. This is primarily happening because households are stressed because a lot of people have lost their jobs and have not managed to get them back. Those who managed to retain jobs have been subjected to salary cuts. Those who were laid off, even if they managed to get another job, mostly got one at a lower salary level. So, gold is the last resort for them,” says Devendra Kumar Pant, chief economist, India Ratings and Research.

Beneath the robust consumption story of India’s middle class that fuelled growth in the second decade of the 21st century was the hidden truth of mounting debt on households — something that nobody was willing to address when it was building up. Dipti Deshpande, principal economist, CRISIL, said that in the period between 2006 and 2017, private final consumption expenditure grew at a healthy pace of 7 per cent on an average. “This story somewhat changed in fiscal 2018 when consumption growth started somewhat decelerating as income growth slowed (proxied by lower GDP growth). The average Indian, however, supported some part of the consumption by dipping into savings as well as taking on somewhat higher leverage,” she told Outlook Business.

India’s household financial savings, which averaged 13 per cent of the GDP up to 2014-15, came down to 11 per cent by 2019-20. By the December quarter of 2020-21, household savings dropped to a dismal 8.2 per cent of the GDP. According to the All India Debt and Investment Survey conducted by the National Statistical Office, between 2012 and 2018, the average debt of the country’s rural households shot up nearly 84 per cent to Rs 59,748 by June 2018 from Rs 32,522 in 2012. In the case of urban households, it increased by 42 per cent to around Rs 1,20,000 in the same period.

Unemployment, Uncertainty, Loans

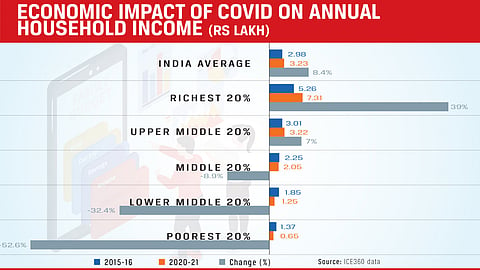

The acute distress in the Indian economy has been caught in the latest ICE360 Survey 2021 of think tank People Research on India’s Consumer Economy. It found that the annual income of India’s poorest 20 per cent households fell by 53 per cent in 2020-21 from their 2015-16 levels. In the same period, the richest 20 per cent of India’s households saw their income grow by 39 per cent.

Arun Kumar, a professor at the Institute of Social Sciences, uses the example of Delhi to explain disparity in household incomes. “The Delhi socio-economic survey of 2018 showed that 90 per cent of Delhi households spent less than Rs 25,000, 98 per cent spent less than Rs 50,000 and 47 per cent spent less than Rs 10,000 each month. Delhi’s per capita income is 2.5 times the national per capita income. If we divide these figures by 2.5, then 90 per cent households spend less than Rs 10,000 and 98 per cent spend less than Rs 25,000 a month. One could say that 90 per cent of India is poor, if not extremely poor.”

Since this survey was conducted, the state of the poor and lower middle class has become more precarious. Take the case of Narayani Devi. She ran a small food stall in one of Noida’s busiest office areas. Her sales would partly go in repaying the loan she had taken to set up the stall. Her husband worked as a security guard at an office in Delhi. Their combined incomes would sustain a family of three in Delhi. Then the pandemic struck.

“Everything was over in 2020. My shop has been closed since then. All offices are closed. How will I repay my loan?” asks Devi. Her husband lost his regular job and, since then, has been doing odd jobs to sustain the family. “His situation is uncertain. He gets work one day and loses it the next day. I cook in houses. You cannot run a house with one person’s income,” she adds.

Devi’s mother-in-law had refused to part with the little gold she had when Devi needed money to start her business. But this time, she had no other option but to offer it for a loan for some money in hand. Now, Devi carries the burden of two loans that haunt her every day.

Brisk Business Trap

In Indian families, gold is seen as the ultimate financial security owing to its sentimental value. At the same time, gold loans are generally believed to be a credit trap. When gold is taken to a pawnshop, the loan amount is calculated on the basis of the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, which generally falls in the range of 75 per cent to 90 per cent. It means that the lender gives up to 90 per cent of pledged gold value. But, the catch is—the higher the LTV, the higher is the interest charged. For the borrower, this increases the cost of borrowing. In August 2020, the RBI increased the permissible LTV ratio for loans against the pledge of gold ornaments and jewellery for non-agricultural purposes from 75 per cent to 90 per cent.

Gold loan companies are doing brisk business now, a trend well captured in the RBI data given above. Muthoot Finance, one of the industry leaders in gold loans, says that gold loan companies aggressively marketed their products and leveraged the available opportunity as gold prices were at an all-time high around July-August 2020. “We saw good traction in FY21. Our consolidated AUM grew by 24 per cent and consolidated net profit grew by 21 per cent in this period,” Alexander George Muthoot, joint managing director, The Muthoot Group, tells Outlook Business. The momentum gained by the company during last financial year is likely to sustain in the current year, too, and the company is expecting a gold loan book growth of 15 per cent in the current financial year, he adds. (Read more here)

The other side of this growing business is that when the economy is not doing well, its clients cannot repay loans on time. Earlier this month, Muthoot Finance brought a public notice in national newspapers for auction of 33,000 gold articles. IIFL Finance issued a similar notice around the same time. “There certainly have been concerns about repayments across the board, and it is due to a combination of reasons. General sluggishness in the economy due to Covid-19 has led to reduced economic activity. This has impacted repayments in some ways. Additionally, the reduction in gold prices have also impacted repayment patterns to some extent,” says George Muthoot.

Trapped In The Middle

Rishi Verma, a gold trader in Delhi’s Chandni Chowk, says that the lockdown and restrictions have led to high levels of unemployment. “A lot of people come to us asking for money against gold. My work is on the wholesale side of making jewellery and giving out loans is not my area of work. It shows that people are not earning now the kind of money they used to earn five to six years back,” he says.

Kumar breaks down the class economy of gold loan industry. He says that it is not the rich who loan against gold. It is generally the middle class. “I would imagine that gold is not held by the bottom 60 per cent to 70 per cent of the population. They do not have any savings to buy gold. It is the next 20 per cent to 30 per cent who are pawning the gold. They are the people in trouble,” he adds.

In the second wave, many of the middle-class and lower middle-class families lost most of their savings because of the rising health costs. The pandemic pauperised families that had to deal with illness. “The majority of the people in this category of the population is employed in the unorganised sector or is self-employed. So when they lost income, they would be in need of funds and liquidity. And gold, in Indian households, is a safety mechanism for troubled times,” Kumar explains.

The likes of Roy are the clients of gold loan companies, who tend to figure in industry data. With the companies now resorting to auctioning of pawned gold articles, their distress becomes the subject matter of policy papers. The likes of Devi, on the other hand, are at the bottom of economic hierarchy, whose gold loans will feature only in the anecdotes of social distress.