Akasa Air had a dream debut year in the Indian market after it commenced its domestic operations on 7 August 2022. In a space that has historically been difficult to crack for newcomers, the young low-cost airline bagged 5 per cent market share within just 11 months of flying. As it inched closer to its one-year anniversary, the carrier inducted its 20th aircraft into its fleet, becoming eligible to apply for international operations.

On the surface, things seemed to be going fine for the novice airline that was led by Vinay Dube—an industry veteran with years of experience at multiple American and Indian airlines. On 4 August 2023, the airline sought approval from the Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) to operate on international routes. Once the nod was given, Akasa would become the youngest Indian airline to be permitted to fly over foreign skies.

But, around the same time, the airline was running from pillar to post to fix a dangerous mutiny brewing within its ranks. The problem struck right where it hurts the most for any airline: inside its cockpit.

Fight and Flight

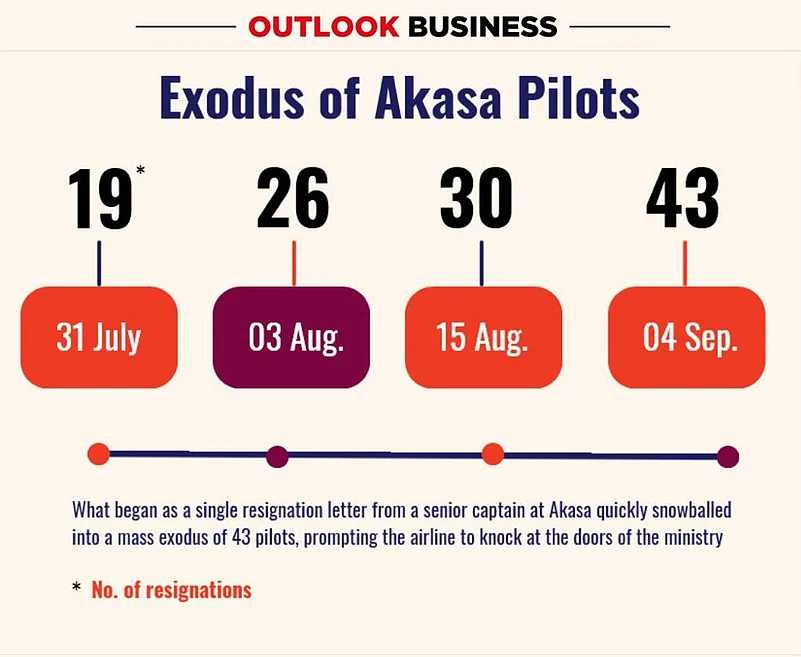

On 3 August, Akasa wrote to the director general at DGCA, seeking the aviation regulator’s intervention in a mass resignation crisis it was facing from its pilots. By then, the airline’s representatives had already met the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) chief, as well as the civil aviation minister and the secretary at MoCA, to inform them of Akasa’s cause of worry. Twenty-six pilots at the airline had tendered their resignations in the past 30 days and none of them were willing to serve their notice periods.

According to the employment agreement signed between the airline and its pilots, a resigning pilot is required to serve a six-month notice period. A similar, if not more demanding, mandate is also set by the civil aviation regulations (CAR) issued by the DGCA although the regulator’s guidelines are now under judicial consideration.

The pilot exodus began on 3 July and the airline, on its part, stated to the regulator that it had disbursed July salaries of the pilots who resigned despite none of them showing up for duty during their supposed notice period. For violating the employment agreement and CAR guidelines, Akasa requested that the regulator debar the pilots who quit suddenly under Rule 39A (2) of the Aircraft Rules (1937).

Akasa also sent a letter to the Bureau of Civil Aviation Security (BCAS) the same day it wrote to DGCA. In this one, the airline highlighted that the pilots not serving their notice period were still in possession of their Aerodrome Entry Permits (AEPs) and that they did not convey any willingness to return them. Calling the continued retention of the permits by the pilots unauthorised, Akasa asked the security regulator to place the pilots who resigned in its ‘Stop-List’ for violation of AEP guidelines.

The letters and meetings with DGCA officials did not do much and the outflow of pilots continued at Akasa Air. On 18 August, the low-cost airline wrote another letter to Jyotiraditya Scindia, the minister of civil aviation, after having met him the previous day. By then, the number of pilot resignations at Akasa had gone beyond 30.

In the letter, the airline suggested to the minister that competing airlines should not get into the practice of hiring pilots who have not served their notice period. This would set a poor precedent that could potentially result in foreign airlines poaching pilots from Indian carriers, thereby resulting in instability for the domestic aviation sector, Akasa argued. The airline also submitted that the sudden exodus of pilots has had an adverse impact on their operations, causing inconvenience to passengers and harming the airline’s reputation.

But all these pleas seemed to fall on deaf ears as Akasa failed to receive any positive response from either the DGCA or the MoCA. “It’s not surprising that the DGCA or the ministry did not take any action. Akasa wanted remedies under the provisions of CAR 2017 which is presently challenged in a court of law. If the matter is sub-judice, what can the regulator do? The answer has to come from a court,” says an industry executive, who does not wish to be named. As the mass resignations continued, and the airline started to bleed financially due to operational difficulties, Akasa turned to the judiciary.

Akasa Flight - Taking to The Court

By the time Akasa filed civil suits at the Bombay High Court against the pilots who quit without serving notice, the number of pilots who quit the airline became 43. For an airline with 20 planes in its fleet, this is a worrying number.

The pilots’ refusal to come to duty for serving notice resulted in several delayed and cancelled flights for Akasa in the month of August. Although the airline tried to prepare for the operational exigencies that were to be caused by pilot exits, its forecast fell short. On 1 August, the airline estimated that 382 of its flights would get cancelled in the coming month. The actual number of flight cancellations for Akasa in that month was 632. For September, Akasa had earlier estimated that it will have to cancel around 600-800 flights but now the airline fears that it may far exceed that number.

As part of the civil suit, Akasa was seeking compensation from the resigned pilots for the revenue drop and reputational harm caused by flight cancellations, delays and rescheduling. According to estimates submitted by the airline at the court, a pilot not serving a notice period of six months results in a drop of Rs 6,96,00,000 in the airline’s operational profit. On top of that, Akasa also claimed that it is eligible for compensation for reputational loss amounting to Rs 14,28,00,000 from each pilot.

Akasa had moved the Bombay HC to prevent the pilots who’d resigned from taking up jobs at any other competing carriers. But the airline was subjected to a rude shock in the courtroom: many of the pilots who submitted their resignation letter in the last one month had already joined a competitor airline.

It is at this juncture that the low-cost carrier decided to take the DGCA and MoCA to the Delhi High Court, seeking the judiciary’s help in getting the aviation authorities to take necessary action against the pilots who refused to serve their notice period. An Akasa representative said in court the airline is now in a state of crisis due to the increasing number of cancelled flights.

Increased cancellations harm the airline in multiple ways. While losing out on revenue that could have been earned, the airline also has to pay for its fixed costs such as airport fees, ground staff renumeration, parking charges, etc. In addition to this, the airline also has to refund ticket amounts and sometimes even book alternate flight tickets from other operators for customers who have been kept hanging because of last-minute cancellations. In the Bombay HC civil suit, Akasa noted that between July and August, booking of alternate flights with competing airlines increased ten times. There was also an increase in customer complaints registered in this period.

The ongoing hearing at the Delhi HC is critical for Akasa because it would be made clear whether the DGCA can take action against the pilots who exited. It would also take into account the long-standing dispute that pilots’ groups have with present notice period requirements as mandated by DGCA. Currently, the aviation regulator stays away from taking any punitive measures under CAR, 2017 because its validity was challenged in the Delhi HC by various pilot organisations. Regarding this, the court had issued interim orders in 2018 and 2019, directing the DGCA to not invoke any coercive action under CAR, 2017 provided the pilots are compliant with their contractual obligations with their employer.

Getting Back on Track

In an internal memo shared with Akasa employees earlier this week, CEO Vinay Dube said that the current turbulence experienced by the airline is caused due to a small set of pilots who abandoned their duties. He also made it clear that it is a choice made by the airline to fly less and give up market share while it tides over ‘short-term constraints’.

Akasa’s trouble is not something new in the Indian market. Other airlines have, in the past, faced trouble from pilots leaving en masse. “I would assume that maybe Akasa would be hiring foreign pilots as an interim action. Getting talent and retaining talent in a market where airline captains are in short supply is a challenge that everybody has to work around,” says Vinamra Longani, a Delhi-based aviation expert.

It might be reassuring for Akasa that its founder Vinay Dube and Aditya Ghosh have faced similar challenges before. Longani adds, “Aditya has dealt with this at IndiGo before and Vinay faced a similar situation when he was CEO at Jet Airways. In fact, Jet had faced hundreds of pilots leaving at once so compared to that this is just a blip for Akasa.”

Since Akasa first moved the Bombay HC seeking injunctions against pilots who quit, there have not been any further resignations. For the airline, which secured its international flying permit from MoCA on Wednesday, the ongoing hearing at the Delhi HC will be important. While the airline is in the process of securing bilateral flying rights, and even placing a three-digit aircraft order before end of the year, it will have to quickly sort out its cockpit struggle.

Further worsening of the crisis, in terms of more cancellations or flight groundings, can have an adverse impact on not just the airline’s financial outlook but also on the reputation it has built over the past one year. Akasa has already taken note of the rising user complaints and negative reviews on online portals. Whether the pilots who quit without serving notice face any coercive action or not, it is critical for Akasa to regain customer trust as the airline sets its eyes on commencing international operations soon.