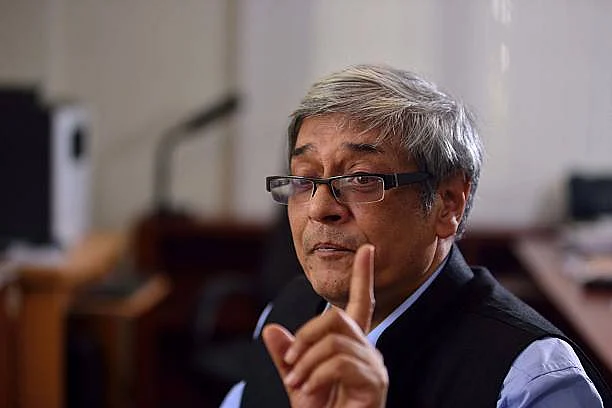

India needs to create 8 million jobs a year, and not 10-12 million, according to Bibek Debroy, chairman of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council.

Amid Lok Sabha elections, Debroy, in a no holds barred interview with Outlook Business spoke about all the things going right with the Indian economy and all the things going wrong.

He says income inequality is not scary just yet, the government should do away with all income tax exemptions, and the argument of southern states over the devolution policy is not justified.

Edited Excerpts

Do you think the current growth momentum, at around 7 per cent, can be sustained till 2030 without a significant boost to demand and consumption? The government has spent a lot, but private investment is still not broad based.

What happens to India in the aggregate is a function of what is happening at the level of states. The Indian government is really a sigma of state GSDP [gross state domestic product] with the exception of things like defense, railways and national highways. A lot of states today are performing far below potential; there is a lot of slack. Government expenditure cannot just mean Union government expenditure, it should also mean state government expenditure. The Union government is very clear about not deviating much from the fiscal consolidation path. Whatever expenditure has been done has mostly been in the nature of capital expenditure.

The growth drivers have to be consumption and private investments. One of the problems of saying anything about the Indian economy is that there are time lags in data. But my reading is investments and consumption are showing signs of recovery. I am reasonably confident that in the next five years, we will have a growth rate of 7 per cent. In all probability, it may be a little bit higher. Some die-hard critics would say India is on a growth band of 6.5–7.5 per cent. We can quibble about it. But on average, we will have 7 per cent in the next five years.

Since you agree growth drivers going forward have to be consumption and private investment, do you not think it is time for India to lower income taxes and remove exemptions to boost consumption?

Whenever I try to reduce taxes to boost consumption, I am doing two different things: firstly, I am creating discretion because I am not reducing it across the board, so there are distortions; and secondly, all resources have opportunity costs—this means whenever I am cutting taxes, I cannot spend that money on something else.

Broadly speaking, there are multiplier effects from cutting taxes, increasing revenue expenditure and capital expenditure. The multiplier effects, theoretically as well as empirically, are greater for capital expenditure, lower for revenue expenditure and lowest for cutting taxes. One reason why I think we have done relatively well post COVID, and lockdown compared to some countries in the West is because we have not cut taxes.

On the thrust of the main question, we need reforms on direct taxes. The reforms are, as you rightly said, the removal of all exemptions. Even today, there are two channels. One channel is with fewer exemptions and [the] other with exemptions for both personal income tax and corporate. The trouble today is not too many people have opted for the fewer exemptions channel. So, the challenge is the new budget will be to incentivise this.

I see no particular reason why taxes for those who are availing exemptions should go down.

You have said in the past that the government is losing revenue because the average goods and services tax (GST) rate is low and suggested it should be at 17 per cent. When you say this, are you concerned about India’s fiscal deficit, especially the debt burden?

We should broadly agree that the GST rate should be the same as the revenue neutral rate. 17 per cent is not my figure, it was the figure calculated by the previous chief economic advisor Arvind Subramanian. There are other estimates of revenue neutral rate as well.

One should recognise that all products are not part of GST today, an ideal GST includes everything. Also, GST has too many rates, I would personally prefer a single GST rate. Most economists do not want a single GST rate. They will say products of mass consumption should have 6 per cent and those for elitist consumption should have 18 per cent.

For the sake of argument, let us take 6, 12 and 18 per cent. In that case, we will spend all our time trying to decide whether an object belongs to 6, 12 or 18. There will be litigation, complications, etc. Today, we do not have only three rates, but six. We must rationalise and harmonise them.

The trouble is everyone who advocates GST reforms wants the 28 per cent to come down, but no one wants the 0 per cent to go up. This is the reason we go round and round.

On what should be the average: Today, the average of the products that are part of GST is less than 11.5 per cent—it is 11.4 per cent. Whether you believe the revenue neutral rate should be 17 per cent or not, I think there is no argument that 11.5 per cent is below it. On average, the GST rate should go up. This is indeed critical for fiscal consolidation.

What do you have to say about the argument put forward by southern states that they are being fleeced by the Centre just to fund the eastern belt?

I think the South versus North issue is grossly simplified. In economic terms, it is not a South versus North issue. Particularly, if it is Tamil Nadu, it is more a political issue.

The economic issue is [that] there are two channels of funding available from the Union government. One is through the finance commission which has two kinds of things: First is, how much of the divisible pool are the states getting in the aggregate, and second is, how it is distributed among states.

As far as the debate is concerned, it is more around the 14th finance commission. Has the Union government deviated from its commitments? It has not. In fact, the 14th finance commission suggested a dramatic increase from 37 per cent to 42 per cent.

So there, I do not see what the argument is.

There is a 7th schedule in the Constitution under which certain subjects are topics for the Union and the states. As a country, do we want [the] Union government to spend [money] on health? I think it is a question all the chief ministers of the south should answer. Today, the Union government does spend on health, but where is health? It is a state subject.

Similarly, two states want the Union government to spend on defence. If they do, should it not be the responsibility of every state to contribute to that? All states get an opportunity to make their representations before the finance commission on both vertical and horizontal counts.

On vertical [count], the Union finance commission sort of gauges the responsibilities of the Union government and local governments, and then arrives at a figure. And then on that, it has a certain formula, which varies from finance commission to finance commission.

If I am unhappy on either of those counts, it means I have not been able to advance my arguments convincingly before the finance commission. This means either there is a problem with the content of my argument or with the way I am communicating it. The forum for addressing this is not the public domain unless you can prove the Union government has not implemented the recommendation of the finance commission.

The second part is centrally sponsored schemes. There are central schemes that are 100 per cent funded by the Union government, and then there are schemes that have a matching grant.

The argument made by the 14th finance commission to increase [devolution share] from 37 per cent to 42 per cent was that most of the centrally sponsored schemes are in social sectors. We have increased your share of the un-tied 42 percent.

Central social sector schemes are tied because we have to do it for this; you have to do it for that. So, you are complaining about the tying part. Since these are in social sectors, I have increased it from 37 to 42, now what is your problem?

The third argument is about borrowing limits. Just for the sake of argument, suppose state government X differs. Can you actually contemplate a situation where state X defaults and goes bankrupt? No. What will happen is that the Union government will bail it out.

So, if the Union government we all acknowledge will bail out the state government, then the Union government through RBI (Reserve Bank of India) should have some mechanism for controlling how much you are going to borrow.

We should scrutinise much more what state governments are spending and what they have done with the recommendations of the state finance commissions. If we ask them, then we will discover that the reason state governments are in a mess despite GST revenue having been good for them is because they are spending on the short term rather than long term.

Since the day the International Labour Organization (ILO) report came out, the issue of unemployment is once again being discussed. Why are we not able to create sufficient jobs, especially for the youth, even after growing at this rate?

I would begin with a clear admission that the quality of our data on labour employment leaves a lot to be desired. If the quality of the data is not good enough, then every researcher tries to make assumptions. The ILO report has also made such assumptions. In the sense, it has spliced the PLFS [Periodic Labor Force Survey] with the NSS and their assumptions are completely different, so I should not be splicing the two particularly if I am doing a time series. But what can you possibly do because PLFS did not exist before 2017. So, let us get that out of the way.

There are problems with the ILO report, but if I were to try to do a time series, I would have done no different because of the quality of our data. If we are growing at 7 per cent, some jobs must be created unless I assume that productivity is also growing at 7 per cent.

Let us not argue that no jobs are being created and recognise something which is not recognised quite often—that the rate of population growth in India has dropped to about 0.8 per cent. It is no longer 1.3 per cent or 1.5 per cent. The number of children in the 0 to 15 age group has declined since 2019, not only as a share, but in absolute numbers.

If you look up an old record of the former planning commission, whether of the SP Gupta Committee or the Montek Singh Ahluwalia committee, and you say we need to create 10 to 12 million jobs a year, then that is wrong. We do not need that many. How many jobs do we need to create a year? How does one know? But I am guessing about 8 million. Growing at 7 per cent, are we creating 8 million jobs a year, is that my claim?

No. But to say we are creating zero jobs is also not correct. I think we are creating 4 to 5 million jobs a year, but we should be creating about 8 [million]. The employment elasticity of growth has declined. It has not declined since 2014, it has been declining since 1999–2000. It has been continuously declining down the years.

So, it is a fact that not enough jobs are being created.

But I should also say this: I do not think it is an all-India issue, because you will find states in India where people are saying we do not get people. You will find states in India where people are clamouring for a few jobs in the railways. You have both things happening at the same time.

When the ILO report came out, the chief economic advisor made an interesting statement that the government cannot solve issues like unemployment.

I think [the] media is guilty of using mischievous headlines. I am sure his intention was to make it clear that jobs cannot be created by the government, and it can only create an environment for jobs. Out of our total workforce of 480 million, only 20 million [people] work for the government.

But would we not be creating many more jobs had the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) sector not been affected the way it was by the pandemic and reforms like GST and demonetisation?

Maybe yes or maybe no. The average MSME employs 1.5 people. It includes the service sector. There are large MSMEs—about 25,000 of them—and then there are the smaller ones. If the MSMEs are in bad shape because they cannot survive after becoming part of GST, it is too bad. If MSMEs were producing sub-standard and fake drugs in garages and if we are now insisting on good manufacturing practices for which they have to close down, then again, too bad.

We know MSMEs have not been doing too well, and I agree that they are in labour-intensive sectors. But the key question is what the competitive advantage of MSMEs are. Unless we answer that and define what MSMEs are, I do not think it leads to any policy conclusion. We recognise that there are economies of scale, if not in production, certainly in distribution. So, what is it that the MSMEs bring to the market?

A recent report by French economist Thomas Piketty has argued that income inequality in India today is far worse than the British-colonial period. The report has been severely criticised by Indian economists—but even if we keep this report aside, do you not think the inequality is indeed continuously increasing?

Suppose I want to get a worker. Somewhere in Bihar, I can get that worker for Rs 15,000 a month. Will I get a worker for Rs 15,000 a month in Delhi? I would not. He [the worker] will have to spend Rs 10,000 on rent in Delhi, which will not be the case in Bihar. So, before we jump up and down about wages in urban and rural [areas], let us recognise there are two factors, which make [the] cost of living in urban [areas], particularly metros, very high. One is housing, and [the] second is transport.

Before I make any assertions about this kind of wage differential, I need to correct for these, which is not easy to do by the way. We do not collect data on income. We never have. We collect data on consumption distributions. And all estimates of inequality in India have been based on consumption distribution. The problem is that we do not have any NSS [National Sample Survey] consumption expenditure after 2011–12. If I do not have data, people will make this and that assumption.

The consumption data we have is from PLFS [Periodic Labour Force Survey]. The consumption of the poor, meaning the lower 10 per cent, has been going up, so has that of the higher 10 per cent. In a relative sense, people who are suffering are not the bottom 20 per cent, but the middle is getting squeezed. This is not happening in rural, but in urban areas. And empirically there are studies, that when an economy grows fast, inequality goes up. [The] question is has it shot up to alarming levels? Our study shows no.

The section that has got squeezed is those of fixed-salary earners (middle class). This makes sense because the government has done a lot for the poor.

Some critics argue India should focus on strengthening its services sector instead of investing on creating a balance by increasing manufacturing’s share of GDP.

Why does it have to be either-or? Every large country has had both manufacturing and services grow. It is a different matter that for a long time we were not part of the global supply chain. Now, for the first time in several years, thanks to PLI and partly through other initiatives, India is now becoming part of the global supply chain. Manufacturing is doing well. One should not use [the] share of GDP as an indicator, because if [the] share of GDP has to grow, it can only be at the expense of something else.

There have been several discussions about India’s statistics system. Numerous economists have questioned the reliability of GDP numbers and delays in important surveys. How big is this concern for India’s policymakers and by when can it be addressed?

Anyone who seriously suggests the Indian government is consciously fudging data is being very irresponsible. No government ever in India, not just this government, consciously fudges data. Of course, there are problems with data. Everything does not come into the public domain, but the government and the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation are trying to improve the system. Criticism of the statistical system has not only been coming from outside the government, but also within the government.

Given the current geopolitical scenario, do you think we will be able to become a $5 trillion economy by 2026–27? And since we are at around $3.5 trillion from $2.8 trillion in 2019–19, when this target was aspired, and the dollar has also depreciated 10% in the meanwhile, does it mean that we are at the same place where we began?

Whenever I have a dollar figure, it depends on the real growth rate, inflation rate and exchange rate. It was an aspirational target made with certain assumptions about all these and economic surveys of the time. So, it is not like we would not get there, but we have lost three years in the process.

Over a period of time, no one knows how the exchange rate will behave. As a trend, when an economy does well, the exchange rate tends to appreciate. Depreciation also depends on different rates of inflation. Our rates of inflation are still high compared to the West. I think the bottom line is that India is growing.

When the Economic Survey at the time did its computation, it worked out that [for] India to achieve $5 trillion it needed to grow at 8.5 per cent, which has not been the case. That is how one should look at this target.

The present CEA [chief economic advisor] and IMF [International Monetary Fund] have made some assertions. I think both say 2026–27. But the concern should be more about becoming a developed economy by 2047.