In March of this year, the Punjab government, facing desperate circumstances, decided to shut down the internet for nearly a week. Their goal was to control the law and order situation in the state, sparked by an extensive police search operation aimed at arresting separatist leader Amrit Pal Singh. While the internet blackout proved effective in thwarting miscreants and preserving order, it brought the lives of common people to an abrupt standstill.

The ramifications of this shutdown were profound. It disrupted education and halted cab services across the state. However, when viewed in the context of preventing mass-scale violence that could result in loss of life and property, these inconveniences seemed a small price to pay.

But beneath the surface of these shutdowns lies a darker truth. Not long ago, a video depicting horrific sexual violence from strife-torn Manipur went viral across India. While the shocking nature of the crime rattled the nation's conscience, another disturbing fact emerged – the video reached the public eye two months after the actual incident had occurred. During that intervening period, Manipur was under an internet shutdown. It was only after a public outcry that the state government and the central authorities took notice. One can only imagine how many similar horror stories may have been silenced during those periods when the internet was inaccessible in the state.

For a vast country like India, internet shutdowns have become a common tactic employed by governments to maintain control during volatile conditions. According to a report by the global non-profit Internet Society, the economic cost of internet shutdowns in India during the first half of 2023 amounted to a staggering $1.9 billion, following last year's figure of $2.3 billion.

A 2023 report by global internet advocacy group Access Now noted that out of the 187 internet shutdowns across the world in the previous year, India accounted for 84 of them. This made India the world leader in issuing internet shutdowns for the fifth consecutive year. Critics say that the unrestraint use of internet shutdowns does not bode well with the country’s achievements in developing indigenous digital infrastructure for its public in sectors like instant payments and e-governance.

Government’s Dilemma on Internet Shutdowns in India

A landmark judgment in January 2020 by the Supreme Court in the case of Anuradha Bhasin vs. Union of India ruled that any internet restriction must adhere to the principle of proportionality and must not extend beyond the necessary duration.

To find a more effective alternative to blanket bans, the Standing Committee on Communications and Information Technology presented a series of recommendations to the DoT in 2021. Among these was a suggestion to selectively restrict certain online services instead of imposing complete internet bans.

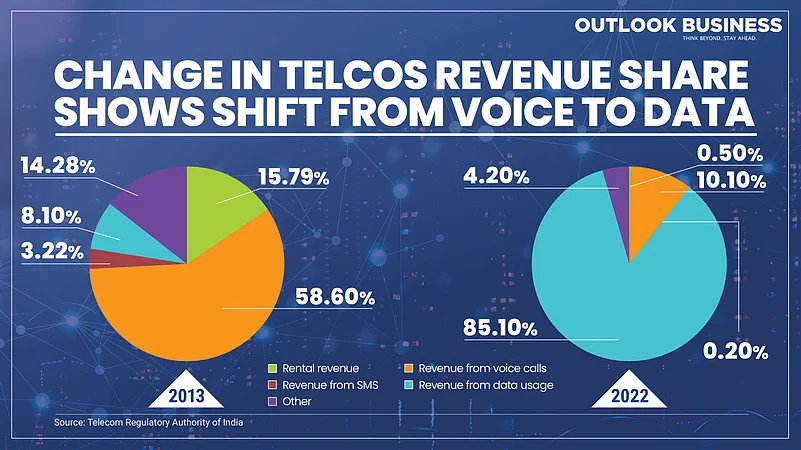

The government acknowledges the cost blanket bans inflict on the economy and its citizens. Presently, following a request from the DoT, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) is soliciting comments from stakeholders on how to implement selective bans on over-the-top (OTT) apps used for communication, such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and Signal.

However, the implementation of selective ban across specific geographies poses significant technical and privacy challenges, notwithstanding whether the ban is implemented from the OTT platform’s end, or from the telecom service providers’ (TSP) / internet service providers’ (ISP) end.

“Selective banning is a technically infeasible solution, and it has grave privacy implications. If done at the OTT level itself, it’s through GPS or location tracking and this is a privacy-invasive mechanism,” says Shruti Shreya, senior programme manager at The Dialogue, a New Delhi-based tech policy think-tank.

If a specific OTT communications service such as WhatsApp or Telegram is asked by the government to make itself unavailable to users within a specific geography, it cannot be achieved without tracking the users’ location data. Such data collection goes against the principles of the recently enacted Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, which calls for minimal data collection.

Although telecom companies can utilise cell carrier tower data to track a connected device’s location, there are other challenges to selectively banning apps from the TSPs’ end. Lt. Gen. S.P. Kochhar, director general at the Cell Operators’ Association of India (COAI), says, “The barring through TSPs can only be implemented at network levels and selective and geographical barring has many difficulties, like overriding using a VPN, changing URLs, dynamically changing IPs, etc.”

Virtual private networks (VPNs) refer to encrypted internet connections that allow users to disguise their online identity. Using this mechanism, internet users can change their virtual location and gain access to content that may be restricted in their actual geographical location.

Internet service providers can also restrict the services of OTT applications by blocking the IP address used by the app. However, OTT apps with tens of thousands of users often do not rely on a single IP address and instead continuously shift between multiple IP addresses, a practice known as dynamic IP. Mandating OTTs to switch to static IPs, as opposed to dynamic ones, could potentially create cybersecurity vulnerabilities for these services.

The central question in the discussion around selective app banning revolves around what constitutes a communication service app. With the proliferation of apps like WhatsApp and Telegram, which offer both communication and other services, defining the boundaries becomes challenging.

Rahil Chatterjee, senior associate at Ikigai Law, points out that there is a blurred line, as applications can serve multiple functions, including communication. For instance, apps like Google Pay or Paytm, primarily designed for financial services, also enable users to exchange messages. Regulating such apps as communication apps or requiring all communication service providers to obtain specific licenses introduces additional compliance burdens for app providers.

Any regulation that approves of such selective banning will be unfair to the OTT app industry, feels Chatterjee. He says, “Making the OTT apps comply with such a framework disincentivises the entire OTT industry that caters to evolving consumer needs. Not to mention the compliance costs and technical challenges this will entail while the main issue remains unaddressed because users migrate to a competing app that is not banned.”

The fundamental question that remains unaddressed is whether restrictions on communication can effectively combat the spread of misinformation during sensitive times. Often, the administration cites 'public safety' as a reason for executing restrictive measures on the internet, such as blocking objectionable content under Section 69A of the IT Act. Even in the proposed selective OTT ban, there’s lack of clear definitions.

“One criterion of legality that tends to get abused or misused is the one of public order. That is a term that gets used extremely loosely. And it’s been used by the executive in too many ways to restrict or block content,” points out Prateek Waghre, policy director at Internet Freedom Foundation. He emphasises that the onus is on the executive to demonstrate how blocking or restricting communication apps can effectively combat dangerous misinformation.

Out Of Jurisdiction

It is important to note that the TRAI paper does not mention anywhere that the possible selective banning of OTT apps is a replacement for blanket internet shutdowns. In fact, there is a lack of clarity regarding why the DoT and TRAI are delving into this matter when the Ministry of Electronics and IT (MeitY) already carries out content blocking over OTT platforms.

Shruti Shreya underscores the concerns associated with TRAI's involvement in OTT services, stating that it falls outside the purview of TRAI's responsibilities. “So, when a government institution delves into something which is not their prerogative, it not just leads to legal implications but also causes disharmony. It can lead to regulatory uncertainties and an increase in unnecessary burden for the [OTT] companies,” she says.

Currently, OTT platforms face regulation from MeitY, DoT, and the Ministry of Broadcast and Information (MIB), resulting in significant pressure on these platforms. However, before imposing further rules on implementing communication lockdowns, there is a need to assess the actual impact of such measures.

Experts argue that there is no existing evidence to demonstrate that communication restrictions effectively improve situations during law-and-order crises. It is also worth noting that the standing committee which recommended the idea of selective OTT bans had also suggested an assessment of the impact of communication shutdowns on law and order. While the former has received attention, the latter remains unaddressed.

In addition to studying the impact of communication curbs, there is a need to establish a uniform set of standard operating procedures (SOPs) and guidelines that help states avoid unwarranted shutdowns, as suggested by the Committee. Without accurate data justifying these restrictions, the rush to selectively ban OTT apps during sensitive times would contradict the vision of 'Digital India’.

Waghre highlights the ongoing push for digitalisation of services, which increasingly relies on the internet. “We are now pushing for more and more services to be digitalised. Essentially, we are moving large parts of the government service delivery layer to the internet. In such cases, to have the internet shut down or to have restricted connectivity is antithetical to the government which wants to digitalise more and more,” he says.

Incidents from Manipur and elsewhere have demonstrated that communication blockades can have disastrous consequences. Given the technical and regulatory challenges surrounding selective OTT bans, hasty regulation in this regard would only increase compliance burdens on OTT service providers. Deciding whether selective bans can serve any purpose or not should be based on a comprehensive national study of the impact of internet shutdowns.