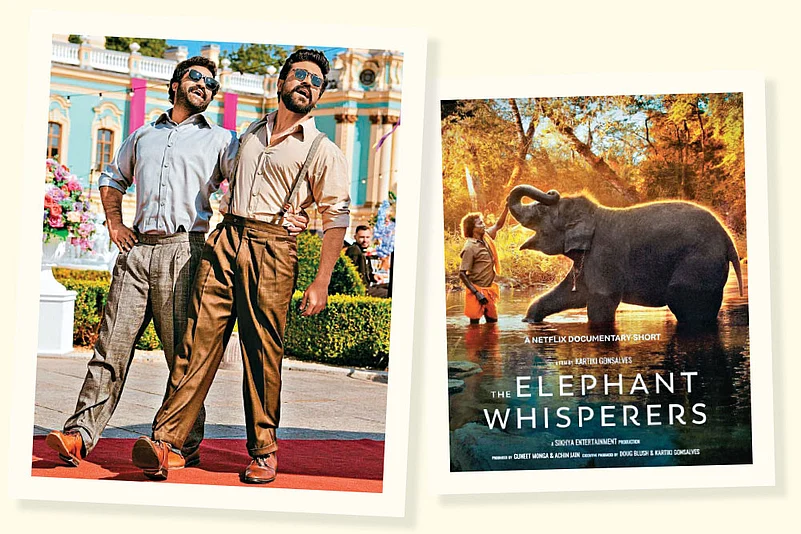

Naatu Naatu from Telugu film RRR has attained a cult status worldwide—going by the frenzy around it, it would not be an exaggeration to say that. Written by Chandrabose and composed by M.M. Keeravani, the song, which has Telugu actors Jr NTR and Ram Charan showing off their dancing skills, pulled off what no previous film song from India, or for that matter, any other country from Asia, has been able to do so far—winning the Oscar, in the “Best Original Song” category. Within 24 hours of the announcement at the 95th Academy Awards ceremony in Los Angeles on March 13, the song garnered eight million views on official YouTube channels, according to a Times of India report, which cited data from Lahari Recording Company, owner of the film’s world music rights.

In a country desperately waiting for decades for the Oscar—universally deemed to be more prestigious than any other international cinema award—the success of Naatu Naatu has put the growing power of Indian cinema at the global level in sharp focus.

Down the years, the Western cinema universe, especially Hollywood, had been rather dismissive of Indian cinema, known collectively as Bollywood, primarily for its colourful and musical song-and-dance routine. Ironically, Naatu Naatu is a song as dramatic as any other typical Bollywood number that has left an otherwise squeamish West singing hosannas to it. It has not only elicited unstinting praise from many Hollywood greats but also pipped global singing sensations like Rihanna and Lady Gaga, who were nominated in the same category, to the post.

A Long Wait

Not everyone back home had pinned high hopes on Naatu Naatu after it was nominated for the Oscars. Doubting Thomases remained sceptical even after it won the prestigious Golden Globe award in January and followed it up with the Los Angeles Film Critics Association award. Such recognitions were summarily brushed aside as mere flashes in the pan. It took an Oscar award to finally silence the carping critics.

For the Indian film industry, it is no longer a dream. After all, an Oscar is widely considered to be the ultimate yardstick for judging any film at the international level.

Curiously, many critics did not think Naatu Naatu to be worthy of an international award, let alone an Oscar or a Golden Globe. Some of them contended that it is not even as catchy as composer A.R. Rahman and lyricist Gulzar’s popular song Jai Ho from British filmmaker Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire (2008), which had won the Academy Award in the same category. Naatu Naatu, at best, sounded to them like a passable composition, hardly deserving all the accolades that the West was liberally showering on it.

Nonetheless, what they all seemed to have conveniently forgotten is the fact that the decades-long yawning gap between the Western and Indian cinema has bridged considerably in the digital era. The advent of global OTT platforms has almost blurred what was once the great divide between India and the West. Today, the latter has given up on its contemptuous attitude towards Bollywood, especially its mainstream films.

Barring rare exceptions like Satyajit Ray who was conferred with the lifetime achievement award by the Academy in 1992, Indian cinema, especially Bollywood, was generally mocked at by the West as being overtly melodramatic, replete with nonsensical songs and dances. With the ultimate honour bestowed on Naatu Naatu by the Academy, it seems the West has either mellowed or become worldly-wise in its evaluation of Indian cinema.

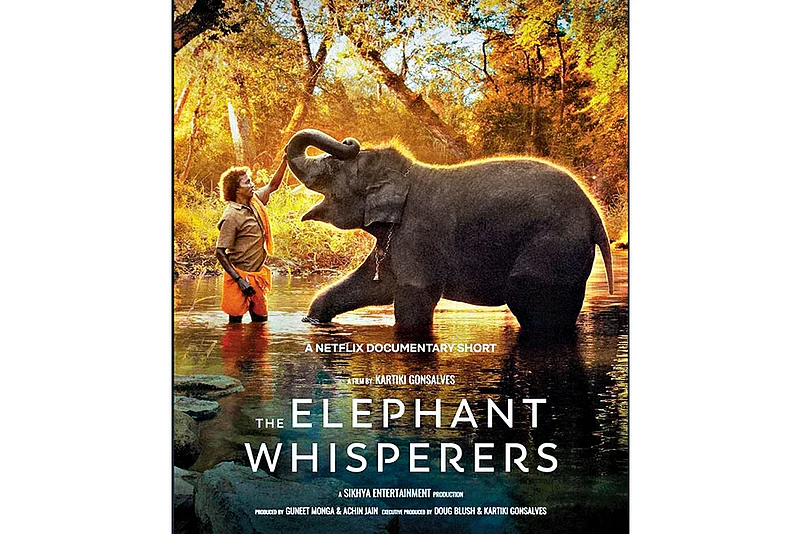

In fact, this year’s Academy Awards brought double delights for India as The Elephant Whisperers also bagged the best short documentary award. It became the first film produced in India to win in the “Documentary Short Film” category. Producer Guneet Monga and director Kartiki Gonsalves, who helmed this docu-short feature created history by becoming the first Indian producer and director to achieve this recognition.

It is not as though an Oscar award had always eluded an Indian talent. Besides Rahman and Gulzar, Resul Pookutty bagged an Oscar for Slumdog Millionaire—under the “Best Sound Mixing” category. Earlier, Bhanu Athaiya won the award for “Best Costume Design” in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982). But then, both films were made by British filmmakers.

The success of RRR is, therefore, unique in the sense that it is an indigenous feature film made in the country, that too written and produced in Telugu. In this context, the success of Naatu Naatu becomes even bigger. Much of its credit, of course, goes to director Rajamouli for the way it was picturised on the screen. While most Indian filmmakers would have been content with shooting the song in the backdrop of an artificial set of a palace created at Film City in Mumbai or in the sprawling Ramoji Studios in Hyderabad, Rajamouli took the entire unit to shoot in front of the majestic presidential palace in Ukraine. Thankfully, it happened just a few months before the country was pushed into a war with Russia. The picturisation looked splendid on screen, and apparently cast a spell on the jury of all international awards, including the Oscars.

Now Awaited: Best Film Oscar

Historically, a few films made by Indian filmmakers—Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar (1946) and Mehboob Khan’s Mother India (1957) to Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay (1988) and Shekhar Kapur’s Bandit Queen (1994), to name a few—received international acclaim, but none of them could ever win an Oscar. Will that be a possibility now?

On the face of it, Indian cinema still has to travel a long distance in spite of the success of Naatu Naatu. When it comes to producing quality cinema, there is no denying the fact that it lags behind small countries such as South Korea, Israel, Turkey or Iran that are making excellent films by the dozen. Bollywood or any of our regional language films are no patch on them in terms of quality.

However, this year’s successes at the Oscars have raised the expectations from Indian cinema. In the past two decades, India has emerged as an important hub for global cinema, primarily because of its ever-expanding cinema market.

Back in the early 1990s, the opening up of the Indian markets in the post-liberalisation era saw the country’s emergence as a huge market waiting to be tapped by international filmmakers. It also led to the rise of a huge Indian diaspora, not only in the US and Europe but also in Asian countries such as China and Japan. It subsequently fuelled the demand for Bollywood movies across the world and turned a young star like Shah Rukh Khan into a “demigod” of the box office. The overseas collections at the ticket counters often exceeded the total production budget of his films.

The arrival of the global OTT platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video and Disney-Hotstar in the past few years also proved to be a win-win situation for both sides—the makers and the viewers.

Rise of the Asians

All these factors have ensured that the Western film studios or OTT platforms can no longer ignore Indian films. But then, it is not only Indian cinema but the whole of Asian cinema that has emerged big on the global centre-stage. This year, at the Oscars, Michelle Yeoh became the first woman of Asian descent to win the “Best Actress” award for her performance in Everything Everywhere All At Once. Three years ago, a Korean film Parasite created a stir by winning the “Best Picture” award at the Oscars. This is not happening simply because India, or Asia, has emerged as a big market but also because the entire region has started proving itself to be a superpower in filmmaking. Only India must catch up with countries like South Korea and Iran.

Bollywood’s movie moguls will have to understand that there are no iron curtains between their films and the Oscars now.

RRR has shown the way and others too can hope to reach the Academy Awards stage. Naatu Naatu has proved the mettle of Indian film music but the complete script of success in the international arena cannot be written until the industry makes a Parasite of its own that can bring the “Best Film” Oscar award home.