It was in the year 1990 that 19-year-old Virendra Mhaiskar joined his family’s construction business. Today, he is sitting pretty with a personal net worth of over Rs.5,000 crore, what with IRB Infrastructure Developers emerging as the country’s most dominant highway construction company and clocking revenues of over Rs.5,000 crore from 18 states. While there have been several firsts associated with Mhaiskar’s company, IRB has added yet another feather to its cap by emerging as India’s first infrastructure company to float an infrastructure investment trust (InvIT).

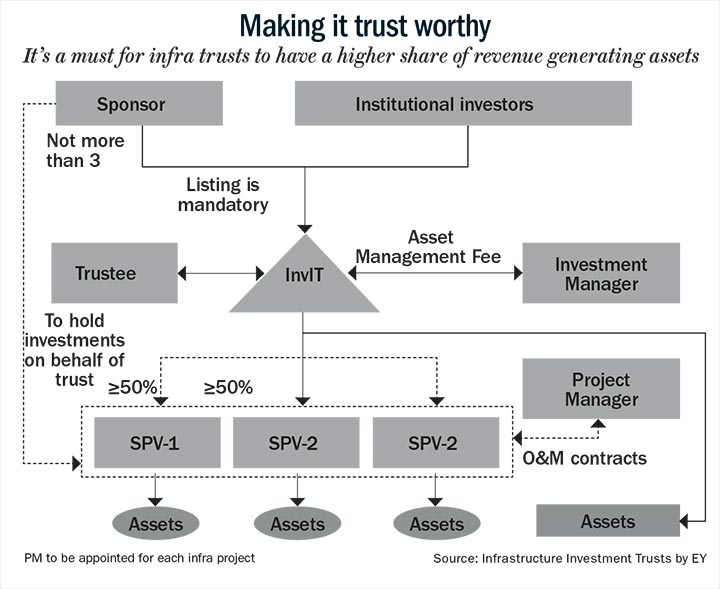

Simply put, InvIT is a vehicle through which leveraged infrastructure companies, listed and unlisted, can hive off some of their assets to the trust, in which the sponsor or the company promoting the trust will hold 25%. The regulations allow infra companies to float two types of InvITs: one which will house completed and revenue-generating infrastructure projects, and the other which has the flexibility to invest in both completed and under-construction projects. While the former can make a public offer of its units, the latter can only opt for a private placement of its units. The units will be listed on the stock exchanges, thus enabling one to trade or invest in them at market determined prices. In a typical InvIT structure, investors will get units equivalent to their equity contribution in these projects held under the trust.

The InvIT regulations stipulate that, firstly, debt cannot exceed 49% of the value of InvIT assets. That is, if the capital employed in the total value of the projects under the SPVs is Rs.100, the debt should not cross Rs.49. Secondly, they will have to invest more than 80% in the revenue-generating projects, which is again kept to eliminate the execution risks (see: Making it trust worthy). Thirdly, 90% of the distributable cash that is generated from these assets needs to be distributed in the form of dividends. Besides dividend and interest payouts, InvIT can also engage in buybacks, thus offering an option for investors looking for an exit. If an investor does not tender units, unutilised proceeds would be distributed as dividend. This notwithstanding, there is a three-year lock-in period from the date of listing, where sponsors or promoters cannot sell their equity. Importantly, the minimum limit is kept at Rs.10 lakh to discourage retail investments in these products.

The prime advantage of InvIT is that it gives the promoting company a chance to reduce the debt burden of its balance sheet, and it gives investors a chance to invest in a smaller and concentrated portfolio of revenue generating infra assets. S. Subramanian, MD and head – investment banking of Axis Capital, says, “InvITs are by and large considered safe since the investment will be made in operational assets and 90% of the cash will be distributed to unit holders.” Importantly, to make it attractive for investors, real estate investment trusts and InvITs have been exempted from dividend distribution tax.

Anshu Kapoor, head private wealth management, Edelweiss Global Wealth Management believes that there is an appetite for such instruments from sophisticated investors such as family offices and institutions and ultra HNIs who are looking for a long-term stable stream of cash flow. “Moreover, unlike a debt instrument, InvITs will also come with some component of capital appreciation. Capital appreciation can happen because of the change in overall interest rates in the economy. Furthermore, let’s say for a road project, if there is increase in traffic, change in credit rating of the issuer, if the trust acquires a new asset or there are any hidden values in these assets—these will naturally have an impact on the price, leading to scope for capital appreciation apart from the dividend income,” adds Kapoor.

Given that infrastructure accounts for the largest share at 33% (Rs.1.98 lakh crore) of the overall banking NPAs as of June 2016, InvIT is being viewed as a vehicle that will bring relief both to the infrastructure player as well as the lender. Mhaiskar believes that in the absence of a robust bond market, InvIT could free up large amounts of bank debt stuck in long-term infra projects.

Mukund Sapre, executive director, IL&FS Transportation Networks (ITNL) believes that the risk profile of InvIT could be far superior to the risk profile of the sponsor company. “An InvIT will mostly have good operational assets. In that case, the companies will be able to refinance debt at lower rates, which will again add to the overall IRR (internal rate of return) of asset under the InvIT,” he says.

The advantage for an ordinary shareholder in a leveraged parent that is the sponsor of the trust is that the money raised through the issue can be redeployed in high-yield projects to reward the shareholders in the main company willing to take a little more risk. Given that the sponsor company will still hold minimum 25% equity in the trust, existing investors will benefit from the economic interest in these projects to the extent of equity participation of the parent company.

Unsurprisingly, a whole bunch of infra companies is now looking at exploring the option. IRB, Sterlite, ITNL, Reliance Infrastructure, GMR and others have lined up their InvIT offerings (see: What’s up for grabs). IRB is the first company to hit the road running.

This is the first of a two-part series. You can read part two here.