The visuals were shocking. Thousands of young women sitting or lying on pavements, railway stations and overbridges across Mumbai. All biding their time for the physical examination of the city police’s recruitment drive early last month. Over 1 lakh had applied for 1,257 posts of constables and drivers.

In June, Maharashtra Police received nearly 18 lakh applications for 17,471 junior posts.

In Ankleshwar, Gujarat, headhunters from Thermax, a Pune-based engineering conglomerate, were in for a surprise. Close to 1,000 candidates had queued up to fill just 44 vacancies leading to a stampede-like situation in July.

Something similar was observed in Mumbai’s Kalina when Air India Airport Services conducted a recruitment drive on July 16. More than 25,000 people showed up for 2,216 handyman positions, causing a near-stampede.

India’s jobs conundrum is a complex, hydra-headed challenge. Not only are the country’s youth desperate to get jobs, there are also questions of skills shortage, a fetish for sarkari jobs and policy bungling by successive governments that moved the focus away from manufacturing to services among other pain points.

Plugging the Hole

Union finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman announced a slew of initiatives while presenting the 2024–25 Budget aimed at tackling issues of skilling and job generation. The schemes, with an outlay of Rs 2 lakh crore for a five-year period, qualify as an acknowledgment of the job crisis, but are not a single solution to the country’s biggest issue.

Besides lack of jobs, there are also questions of skills shortage, a fetish for sarkari jobs and policy bungling by successive governments

The inability to tame this demon is visible in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) even after having secured a third consecutive term at the Centre. “What is clear from the recent elections is that there is a lot of concern about jobs. It can be seen in any data including the millions applying for public sector jobs,” says Raghuram Rajan, former governor of the Reserve Bank of India (see interview).

What has reignited this legacy issue was the India Employment Report 2024, released jointly by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the Institute of Human Development (IHD), before the Lok Sabha elections. According to the report, the share of youths in India’s total unemployed population in 2022 was nearly 83%. Those with secondary-level or higher education accounted for 65.7% of this population, up from 54.2% in 2000.

These numbers deeply resonated with the 1.8 crore first-time voters in the country leading to BJP’s underwhelming electoral performance this year. The Sheikh Hasina government in Bangladesh was not that lucky, though. The issue of reservation and unemployment led to the uprooting of the Hasina government within weeks.

Drawing from its earlier attempt with the production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes to boost manufacturing, the Centre has now introduced employment-linked incentive (ELI) schemes aimed at spurring job creation in the formal sector. The idea is simple—incentivise employers to hire more people. But will these initiatives be enough to make a real impact?

Pronab Sen, former chief statistician of India, is not so sure. “The schemes announced with regards to employment will barely scratch the surface and not go deeper into the issue. It is natural for companies to hire according to their requirement, so it is doubtful if there will be any addition,” he says, alluding to the twin problems of skill gap and muted growth prospects of companies.

Contrary to popular belief, the scarcity of employment opportunities in India’s formal sector is not due to a lack of jobs. In fact, several industries are grappling with a shortage of skilled labour. Sectors like information technology (IT) and financial services are already sounding the alarm over this growing skills gap.

In June, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) reported an inability to fill 80,000 positions due to lack of qualified candidates, highlighting a broader skills gap in the IT industry. As demand for expertise in disruptive technologies soars, the sector faces a shortfall of 6 lakh skilled professionals, according to Nasscom, the sectoral trade body.

The financial services sector is similarly challenged, with 18 lakh vacancies left unfilled last year out of the 46.86 lakh jobs created, as per data from the National Career Services portal.

It’s Complicated

The root of this issue is laid bare in the Economic Survey 2023-24. Despite 65% of India’s population being under the age of 35, many lack the skills needed for today’s economy. “Estimates show that only about 51.25% of the youth are deemed employable. In other words, one in two young people are not yet ready for the workforce straight out of college,” notes the survey, authored by V Anantha Nageswaran, chief economic adviser (CEA) to the Government of India.

“A business which was not planning to hire would not change its mind because one month out of 12 is paid for [a guarantee of one of the schemes]. But if a firm was looking to hire 12 people it might hire one more. Subsidies in the two other schemes are larger over a two-year period. But given that these are through provident fund contributions, the major push would be on turning informal workers into formal ones...Workforce formalisation is rising, and these schemes can help accelerate the process,” says Neelkanth Mishra, Axis Bank’s chief economist and part-time member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister—EAC–PM (see interview).

Among the numerous initiatives, the finance minister has also introduced schemes to enhance the quality of the force. However, this is not the BJP government’s first attempt to address the need for skilling India’s workforce. The much-touted Skill India mission, launched in 2015, delivered lacklustre results. Its flagship programme, the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY), is largely deemed to be a failure, with dismal placement rates of 18.4% for PMKVY 1.0, 23.4% and just 10.1% for version 2.0 and 3.0, respectively.

In the latest avatar of the skills mission, the Centre’s plan involves India’s top 500 companies each taking 4,000 interns and providing them with training. The government is optimistic that this initiative will yield positive results.

In a post-Budget interview to Outlook Business TV Somanathan, Union finance secretary had said though “challenging” the initiative was “doable”.

Yet, when Kartik Narayan, chief executive (staffing) at TeamLease Services, a human resource services company, analyses the shortage in India, he explains why these schemes would not be the proverbial silver bullet. There are over 30 crore jobs for which there are no takers.

“Several factors contribute to India’s shortage, including the prevalence of informal employees, wage issues, educational system constraints, insufficient skill development, migration to other sectors and social stigma associated with manufacturing jobs,” he says.

Compounding the issue, many of the workers who do possess the necessary skills prefer to go abroad, where better pay and opportunities await. In 2020, according to the Ministry of External Affairs, 1.6 crore Indians were living abroad as migrants, with over 80 lakh of them working in West Asia alone. Migration is not necessarily bad for an economy, but the trend shows how the country is unable to retain its talent at a time when domestic industries are desperately seeking skilled labour.

Different Takes

While budgetary measures only focus on the private sector, the public sector too is grappling with vacancies.

In the run-up to the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, the Congress claimed that there were 30 lakh vacant posts in various government departments. The BJP did not contest the number.

Yet, Nageswaran, the CEA, emphasised that it is incorrect to think that the government alone can tame the hydra-headed demon of unemployment.

To this effect the Narendra Modi administration is actively encouraging the youth to broaden their career aspirations beyond government jobs. Sanjeev Sanyal, a member of the Economic Advisory Council (EAC) to the Prime Minister, is advocating for young Indians to pursue careers in creative industries rather than solely aiming for civil service positions.

“While a section of the youth may be stuck in traditional paths like UPSC [Union Public Service Commission] or public sector, many young Indians are taking extraordinary risks. For the first time, we are seeing Indians pursuing sports as a vocation, the emergence of a large number of start-ups and individuals entering completely new professions like social media or artificial intelligence,” he says (see interview).

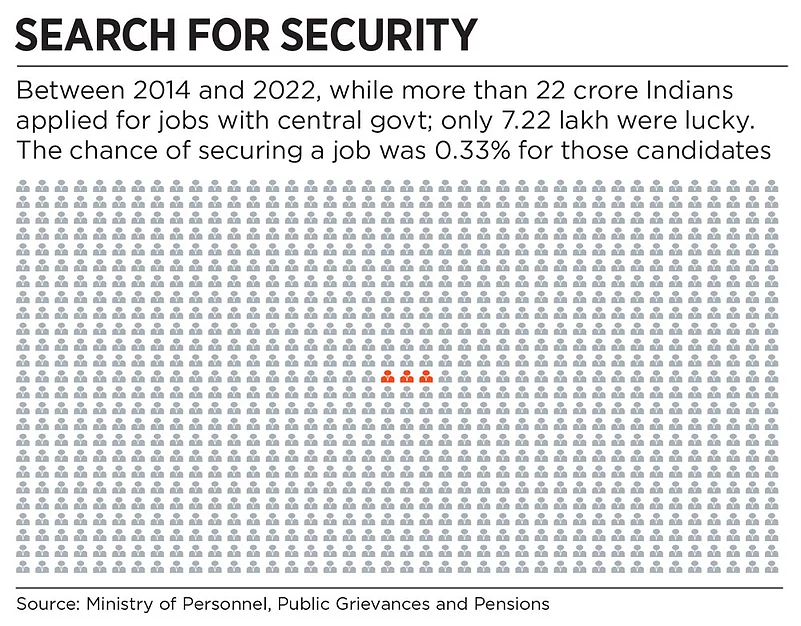

In a striking revelation, the Centre disclosed that between 2014 and 2022, a staggering 22.05 crore job applications were submitted for positions in various central government departments. Yet only a mere 7.22 lakh candidates, or just 0.33%, were actually selected. The intensity of this competition was further highlighted in 2023 when nearly 13 lakh hopefuls sat for the UPSC prelims, all vying for just 1,255 coveted positions.

This relentless pursuit of a limited number of government jobs, despite the overwhelming odds, is what Sanyal describes as a “poverty of aspirations” gripping the nation.

While he identifies the root of this issue in the mindset of these aspirants, the youth have tangible reasons for aggressively pursuing government jobs. Even after more than 75 years of independence, in the absence of state-backed social security schemes they perceive government positions as far more lucrative than those in the private sector.

Course Correction

The problem of joblessness is systemic and goes back decades. In 1991, the central government, led by PV Narasimha Rao, swiftly dismantled India’s socialist policies, opening the economy to market-driven reforms. This shift presented a significant opportunity for the over 70% of the population engaged at that time in agriculture to transition to better-paying jobs in the private sector. The shift to formalisation of jobs began but the manufacturing sector, which was expected to absorb a large portion of this workforce, did not pick up the slack.

According to the India Employment Report 2024, the share of youths in India’s total unemployed population in 2022 was nearly 83%

Instead, India’s economic trajectory favoured the services sector over manufacturing, leaving millions unable to benefit from this transition. When the BJP came to power in 2014 with a promise to eradicate unemployment, Modi vowed to make a historic course correction, aiming to revitalise manufacturing and create jobs at a scale which had been long overdue. His government set an ambitious target to increase the manufacturing sector’s share in gross domestic product (GDP) from the stagnated level of around 16% to 25% by 2025.

Ten years on, although the 25% target remains elusive, the pursuit of this goal has set India’s manufacturing sector on a stronger growth trajectory. A report by analytics company Crisil projects that India’s average manufacturing growth, which hovered around 6% from 1980–91 through 2023–24, is expected to rise significantly to 9.1% between 2024–25 and 2030–31. This uptick suggests that the manufacturing sector could reach a 20% share of GDP for the first time by 2031.

“Manufacturing basically needs land, labour, capital and logistics as inputs. Now, on many of those inputs, the markets continue to remain distorted. We have not done as many reforms in land. For instance, our labour legislation has been passed but subordinate legislation has still not been passed,” says Krishnamurthy Subramanian, former CEA and India’s executive director at the International Monetary Fund (see interview).

He calls for states to take the onus and create land parcels and support the central government with labour codes. “States need to recognise that instead of just focusing on reservation, which is just slicing the pie in different ways, you have to work on growing the overall pie,” he says.

Politics of Allocation

The political sensitivity surrounding land and labour reforms continued after 1991. Successive governments have shied away from taking bold steps due to intense opposition from key voter bases and influential groups like trade unions. Former industry secretary Ajay Dua calls it “the price you pay in a democracy”. The business-oriented BJP, however, was determined to push through these reforms, confident that it could achieve them in its third term. Yet, it may now have to retreat, as evident from the silence on these matters after the elections.

With roadblocks to such necessary reforms, economists believe the Indian economy could only depend on services. “We need to capture every manufacturing job available across the spectrum. But, as a relatively poor country, India has limited resources. The real question is whether we should allocate Rs 75,000 crore to incentives for the chip industry, which will create few jobs and require substantial subsidies to be globally competitive, or invest in stronger engineering colleges and labs that could broaden our technological participation and open up a wider range of opportunities,” says Rajan indicating that his suggestion would go a long way in resolving the issue of skill-gap and mean more employment for India’s IT-focused educated youth.

The Modi government’s budgetary allocation shows that it is not in agreement with Rajan. To promote manufacturing, the Union Budget has increased the allocation for infrastructure projects by a mammoth 333.6% from Rs 2.56 lakh crore in 2014–15 to Rs 11.1 lakh crore in 2024–25. On top of it, the government has earmarked Rs 1.97 lakh crore for 14 PLI schemes since 2021–22—a figure that surpasses the Rs 1.48 lakh crore allocated for education.

But on-ground reality vindicates Rajan.

A large section of the workforce does not have access to enough productive manufacturing jobs, nor the skills needed for white-collar positions in the formal sector. Disillusioned, many are now either fixated on government jobs as their only hope, or reluctantly returning to agriculture after the Covid-19 lockdown. The government’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) confirms this trend of reverse migration, revealing that the share of agriculture in employment increased from 42.5% in 2018–19 to 45.8% in 2022–23.

Narratives at War

The problem appears to have intensified in recent years. In July, Modi, citing a report by the RBI, attempted to counter critics of his administration’s employment policies. “The RBI recently published a report on employment. According to the report, around eight crore new jobs were created in the past three to four years. This figure has silenced those spreading fake narratives on jobs,” he said at an event in Mumbai.

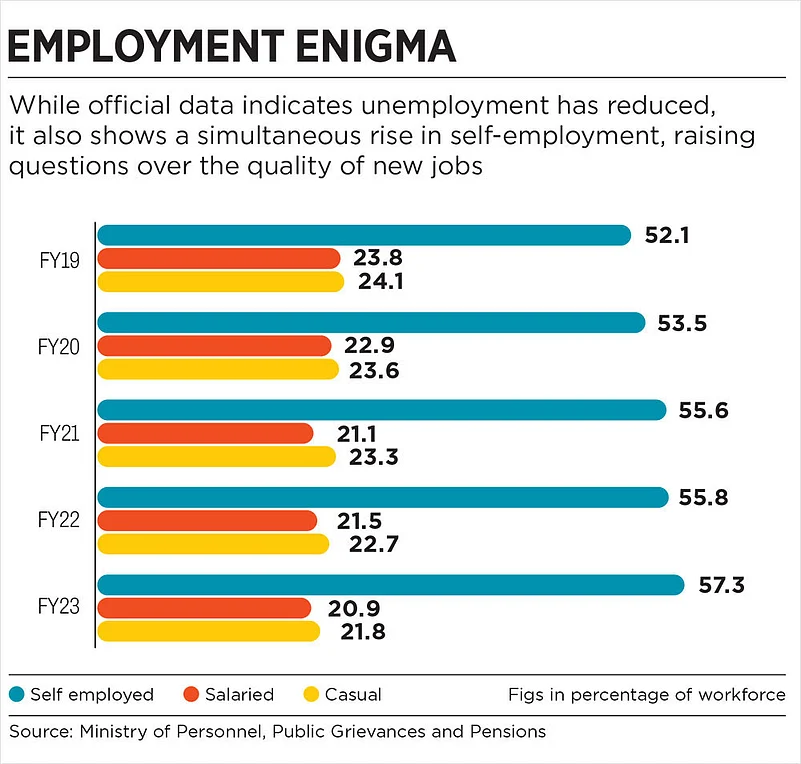

Sen, the former chief statistician, contends that the claim of eight crore new jobs is misleading. He points out that the RBI report shows a significant rise in employment within agriculture and allied activities, construction, health and social welfare—sectors where much of the employment growth is attributed to self-employment rather than stable, formal jobs. Hence, this is not a case of eight crore jobs created in the economy.

Both the Centre and the opposition have been at odds over how to tackle unemployment in India. The Congress, in its manifesto, had championed the micro-, small- and medium-enterprises (MSMEs): “…the MSME sector is the creator of the largest number of jobs, especially for workers with average education and average skills”.

The MSME sector, contributing about 27% to India’s GDP, stands as the country’s second-largest employer after agriculture. The BJP, however, has placed its bet on corporate India for high growth and productivity. So, it has tried to support India Inc with tax reliefs, while some of its policies like the demonetisation and goods and services tax (GST) turned out to be detrimental to small businesses.

Union minister for MSMEs, Jitan Ram Manjhi, recently told the Lok Sabha that nearly 50,000 small businesses have shut down over the past decade.

Through credit support, the Budget has now attempted to offset the damage inflicted on the MSME sector. But Sen says it is not enough. “There is a lot of lip service to MSMEs, but no material support has been offered yet. This shows that there is no integrated plan; instead, there are fragmented efforts, each addressing only what is perceived as a problem,” he says.

On the other hand, Bibek Debroy, chairman of the EAC–PM, questions the quality of jobs the MSMEs will produce. “If the MSMEs are in bad shape because they cannot survive after becoming part of GST, it is too bad. If MSMEs were producing sub-standard and fake drugs in garages and if we are now insisting on good manufacturing practices because of which they have to close down, then again, too bad,” he had said in an earlier interview to Outlook Business.

Debroy added, “We know MSMEs have not been doing too well, and I agree that they are labour-intensive. But the key question is what the competitive advantage of MSMEs is. Unless we answer that and define what MSMEs are, I do not think it leads to any policy conclusion. We recognise that there are economies of scale, if not in production, certainly in distribution. So, what is that the MSMEs bring to the market?”

By prioritising the corporate sector, the BJP government has indeed delivered the economic growth India has long pursued. Between 2014 and 2022, India achieved an average compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.6%. In comparison, a group of 14 other major developing economies recorded an average CAGR of 3.8% during the same period. However, as highlighted by the Economic Survey, this growth has not translated into sufficient job creation and much of India’s demographic dividend remains untapped. The Economic Survey blames industries’ fascination with AI and competitiveness for this situation. However, in a globalised world, it would be hard to expect companies to prefer job creation over improving margins.

Threat to Viksit Bharat

In Ramayana, it took just one well-aimed arrow for Rama to bring down the 10-headed Ravana. Modi has a far more complex challenge when addressing the many faces of unemployment in India. His party’s ambitious vision of Viksit Bharat, a promise to elevate India to a developed nation, has road bumps ahead.

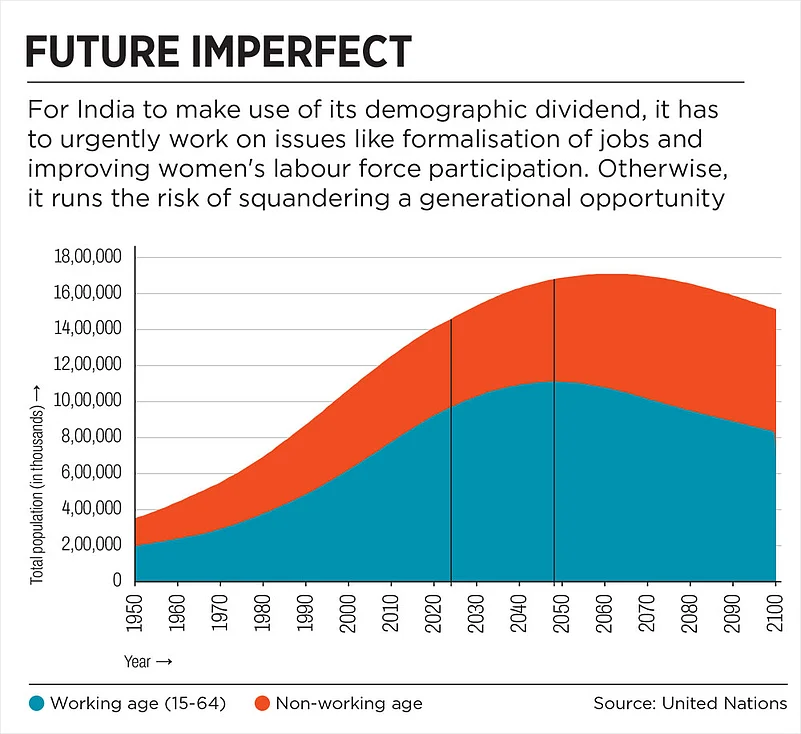

India is, in fact, running out of time to capitalise on its demographic advantage, says a 2022 report by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). Between 2020 and 2030, the country is set to add 10.1 crore people to its working-age population, but this number will drop to 6.1 crore in the following decade, and further to just 2.1 crore thereafter (see graphic above).

If enough jobs are not created and workers are not adequately prepared, this demographic dividend could turn into a liability. Neighbouring Bangladesh provides a stark example of the blows unemployed youth deal to the stability of a country. Any ruling administration must be concerned about the potential for youth protests to escalate into violence, posing significant challenges for the government.

Rajan also strikes a cautionary note in this regard. “If we are not taking advantage of the period where we have a lot of young people coming to the labour force, then we will not get the kind of growth which will propel us into Viksit Bharat status,” he says.

The early signs of these warnings are already visible in the flashy GDP numbers of recent quarters. A glaring gap has emerged between headline growth and consumption. While the country grew at 8.2% in the previous financial year, the private final consumption expenditure (PFCE)—a measure of household consumption—rose by a mere 4%.

With aspirations of transforming India into a developed nation by 2047, one might have expected the Centre to address these issues head-on back in 2014, rather than wait for the current moment of reckoning.

Just one email a week

Just one email a week