In 1976, Bruce Henderson, the celebrated founder of global management consulting firm Boston Consulting Group (BCG), wrote in a memorandum to BCG Partners: “It would be nice to say that I foresaw the future and planned it as it eventually turned out. But at the beginning, for every firm, the overriding question is: Can you survive?” Henderson sensed way back in 1976 that it was not as difficult to reach the top as it was to stay there—strong and committed.

India is home to multiple enterprises that have redefined strength and commitment in their path of survival. They are not only older than the Indian democracy, but stories of their resilience spread through the landscape of 200 years of subjugation under imperial England. Take the case of the Wadia Group. Founded even before the Battle of Plassey, it was established through imperial benevolence as a marine construction company but during the freedom movement placed itself firmly against its benefactors. This is a trajectory that many other old groups, such as the Tatas, also followed. Juxtaposed with these conglomerates are a few, such as the Birlas, whose positioning since inception was nationalistic, making the history of corporate India a fascinating story.

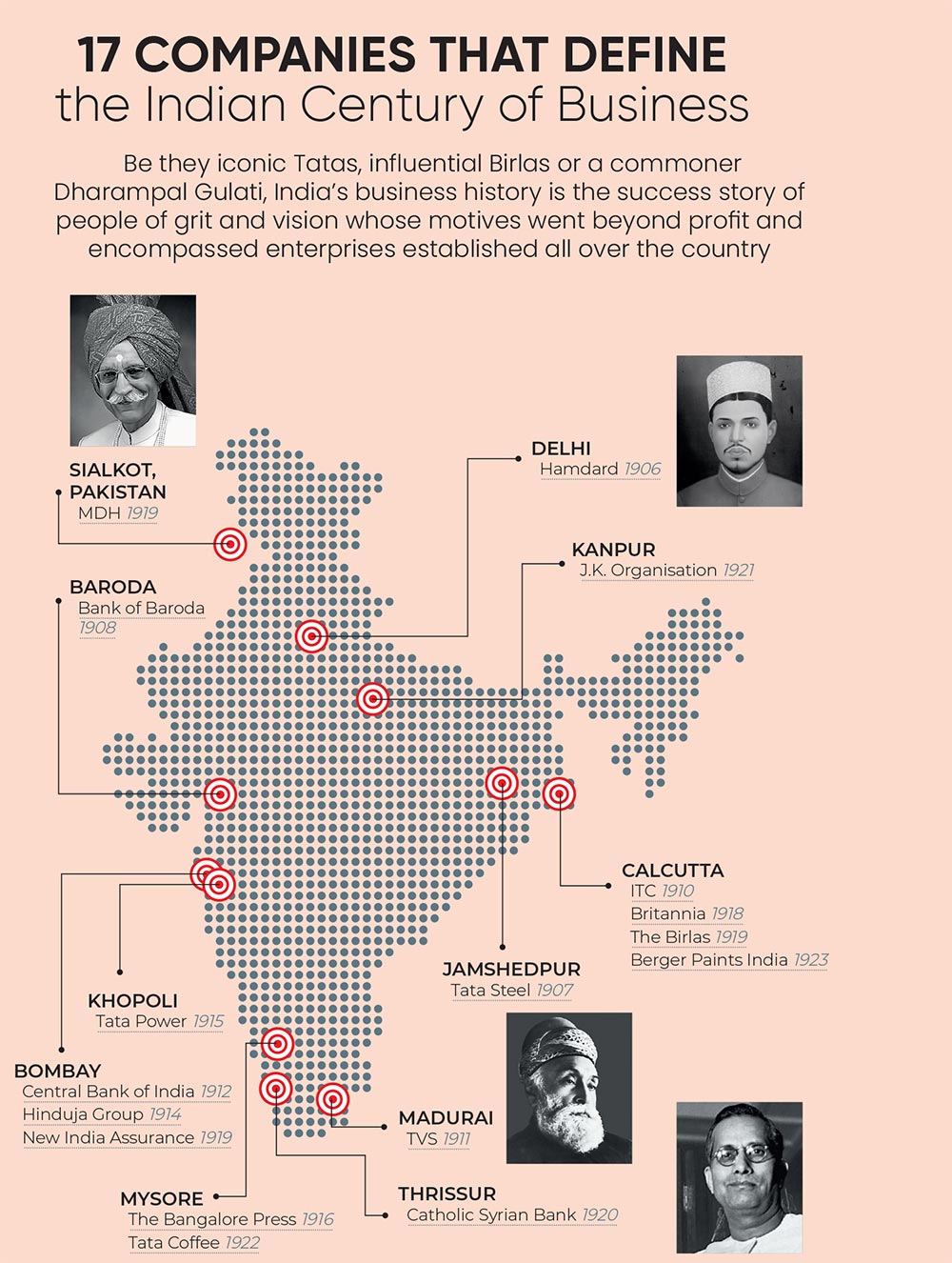

As we train our lens on centennial Indian companies, the question we seek to answer is “What does it take to build a company that lasts 100 years?”

Dinosaurs’ Deft Drive

A journey of 100 years creates excess baggage and creates an impression that a legacy company tends to become irrelevant as a new epoch arrives. Vicky TenHaken, a professor emeritus at Hope College, Michigan, USA, who has studied such companies, argues that centennial corporations have unique survival strategies. She says, “The older companies which have had such a long journey are considered dinosaurs in businesses. There is no denying the fact that there are several things that big companies and centennials do differently.”

Sharing with Outlook Business her observations from her research on companies in Japan and the US, TenHaken says, “Japan has more older companies than America. My observation is that older companies successfully strike a delicate balance between tradition and change, honouring their past. They believe that they have something unique. They stay invested not only to protect it but also to build it further.”

The Tata Group has been a major case study for those interested in legacy business empires in India. Tata’s basket of centennial companies includes Tata Power, Tata Coffee and Indian Hotels Company. While general insurance company New India Assurance was founded by J.R.D. Tata in 1919, it became a public-sector undertaking after being nationalised in 1973. Many attribute the success of the group to its employee-friendly policies and long-term vision. Five years before Tata Iron and Steel Company, Asia’s first integrated private steel company, which was renamed as Tata Steel, was established in 1907, group founder Jamsetji Tata wrote to his son Dorabji about his vision for a planned city with all amenities for employees. We know it today as Jamshedpur.

The most striking feature of the Tata Group is its adherence over the generations to the values and culture set by Jamsetji, say analysts. L.R.K. Krishnan, professor of management at the Vellore Institute of Business, Chennai, believes that one of the profound principles that keeps the company growing is the employee-value proposition and strong corporate mission and culture. According to him, when employee-value proposition—benefits given in return for skills, experience and commitment to the company—is provided, employees are willing to go beyond the call of duty. “The value added incrementally by the employers is far greater in companies which stay relevant for 100 years. These are the companies where employee engagement score is very high, leading to higher customer satisfaction,” he explains.

It is not only employee value proposition, strong corporate culture or even the mission, but also constant reorientation and ability to adapt to new challenges that give the vigour to these companies to stand tall for over a century. In his book The Oxford History of Indian Business, Dwijendra Tripathi, former professor at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, and well-known business historian of India, has said that response to change is the first condition for survival in business.

With a specific example, Krishnan too argues that a significant contributing factor to the success of companies is their ability to reinvent within a larger business logic. “Steel is a cyclical business. It goes through a cycle of up and down every five years. During a low business cycle, most companies do cost control and optimisation. Tata Steel reinvents itself every five years to be ready for a five-year upcycle. The company reinvests in the future,” he says.

In Symbiosis with the Politician

In India, the challenges are not just business cycles or changing technology but also political ideologies. The way India’s early baniyas manoeuvred the courts of Indian princes and offices of East India Company and then put their might behind the Indian national movement has not changed much as the post-independence industry captains are made to tack their boats according to political downwinds.

Businesses want to be seen with the government of the day not just to keep its agencies away, but they actively seek direct benefits from it. Subhash Chandra Garg, who retired as the Union finance secretary in 2019, says that governments have many levers through which they influence business decisions of corporates. “The government has enormous fiscal expenditure programme and large capital expenditure programme in railways, roadways, transportation, etc. Government endorsement can help companies benefit from that,” he says.

He goes to the extent of saying that governments play a leading role in deciding the fortune of companies. “The government policy choices play a huge role in deciding the future of the company. There are companies which are favoured by governments and benefit from their decisions. It will not be wrong to say that governments decide the fortunes of these companies.”

Beyond the government’s favouritism lies another factor that can make or break a company in its long march. While practitioners and academia pour their minds over formulating principles that guide business survival and expansion, no handbook is available for navigating policy inconsistency.

A fairly young democracy that is desperate to shed the weight of Nehruvian-era policymaking, India has become notorious for its policy flip-flops. While the policies of 1991 were the first-generation reforms to liberalise the economy and woo capital, both domestic and international, 2012 could be viewed as a watershed year that reversed the strides made in the preceding decades. In a matter of an hour of his last budget speech, then finance minister Pranab Mukherjee scared investors while the apex court through two rulings scarred them forever. History will remember these measures as retrospective tax amendment and telecom licence cancellation respectively.

Unlike Garg, Arun Kumar, a former professor at the Institute of Social Sciences, Delhi, feels that corporations decide policies. He says, “Policy instability in India for me means cronyism. Take, for example, disinvestment that started long back. There are few businesses which get everything. In India, big businesses manipulate the policy.”

Redefining, Rebranding, Re-energising

Beyond political endorsement, there are organisational and market-driven factors that inform the longevity of these companies. For instance, the principles of adaptability, sensitivity and constant evolution bind many different types of Indian centennial companies in a common thread of relevance. ITC was incorporated on August 24, 1910, as the Imperial Tobacco Company of India Limited. As it dropped tobacco from its name and became ITC Limited in 1974, the company was making itself future-ready. In the new world that it foresaw, a marquee company could not have had tobacco products as its mainstay, and, so, it explored newer areas to dominate.

Chairman and managing director Sanjiv Puri told Outlook Business that ITC’s expansion strategy sought the sectors where there was good headroom to grow and the company’s institutional capabilities could be leveraged. “We have always gone to segments with the commitment that we will invest to become leaders. And when I say leadership, it is not mainly about size. It is not merely about financial metrics, but, very clearly, quality is at the core of our DNA,” he says. (Read the full interview.)

And ITC’s evolution has been phenomenal—from packaging printing business of 1975 to foray into the hospitality sector in 1975 and from setting up an agribusiness division in 1990s to stepping into the IT sector in 2000. Then came its entry into packaged food products in 2001 that made it a household name. This transformation has been lauded by the markets as the ITC stock rallied after years of stagnation.

TenHaken finds common features in global companies that outlast their contemporaries. She says, “In a book, I have suggested five characteristics that help companies become centennial: strong corporate mission and culture; unique core strengths and change management; long-term relationships with business partners; being active members of the local community; and long-term employee relationships.”

R. Gopalkrishnan, former executive director at Tata Sons and author, believes that centennial companies across the world have operated within the “diamond framework” business model. “Imagine a diamond with four corners. The four corners stand for consistency, eco-tolerance, conservatism and sensitivity. All companies which have managed to survive functioned well under this framework,”

he says.

He recalls how Brijmohan Lall Munjal, founder and then chairman of Hero Motor Company, would visit his company distributors often “to have a strong bond” with them, thus underlining the strength a company’s unglamorous network commands in its longevity journey. “In companies like these, brokers and distributors are stronger than the company,” Gopalkrishnan says.

However, post hoc analyses by management gurus and corporate leaders stand at variance with the opinions of policymakers and business historians. The former category is more inclined to attribute the longevity of a centennial company to its leadership and its focus on qualities like values, vision, employee and customer satisfaction, etc., while the latter set prefers to place the success of such companies in the context of political and economic changes. The jury is out on whether one reason trumps the other or must be seen together.