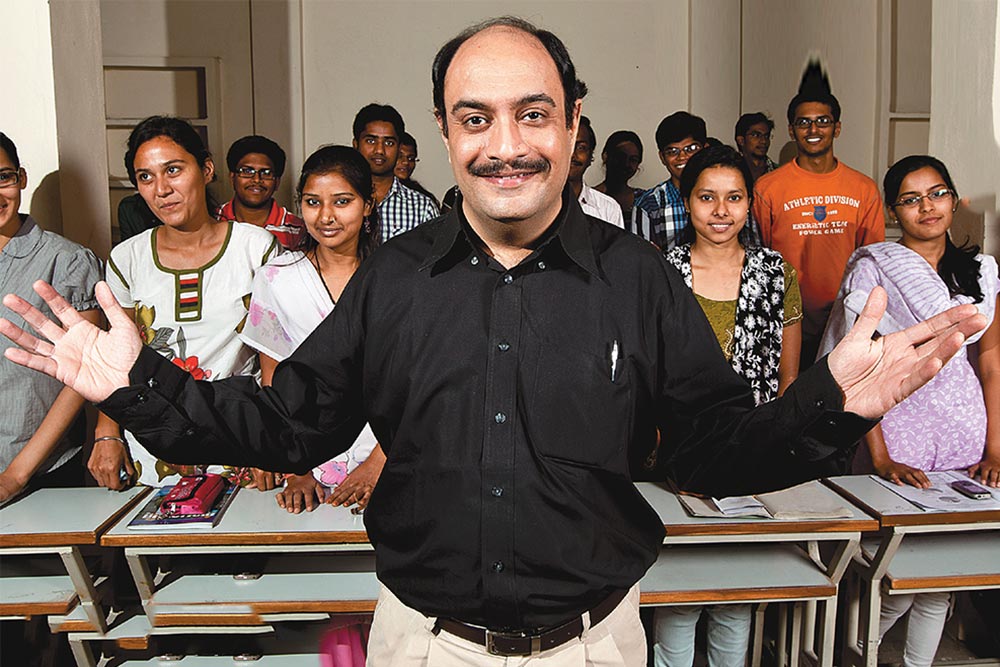

Manek N Daruvala calls himself a self-taught entrepreneur who decided early in his career to bet on his passion for teaching. In the early 1990s, Daruvala took a call to give up his five-year fledgling corporate career in marketing and sales with the Godrej group. However, he did not rush to turn his vocation — teaching math and reasoning to graduate-level students in his spare time — into a full-time occupation overnight. Instead, he chose to play the long game.

Daruvala acquired an MBA degree from IIM-Ahmedabad and then the 28-year-old first scanned the market for MBA coaching classes in Mumbai and other major cities before zeroing in on Hyderabad. Why Hyderabad? “Real estate was cheaper, and there were no popular coaching brands in the city,” he explains. The presence of several well-established colleges potentially ensured a steady flow of MBA-aspirants as students.

Based on some basic back-of-the-envelope calculations of his business model, and relying heavily on his gut feel, he roped in his friend and colleague from Godrej, P Vishwanath, into the venture. Both of them relocated to Hyderabad in 1991 with a corpus of just Rs.24,000 — the partners brought in Rs.8,000 each, along with a loan from a friend. They kick-started their venture, the Triumphant Institute of Management Education (TIME), from a rented 150 sq ft office space in Secunderabad.

To ensure a steady flow of resources to the start-up, Daruvala took up a day-job in his newly adopted city, taking classes early in the morning, and in the evening after work. Vishwanath, meanwhile, dived full-time into the venture, preparing the course material as well as taking classes. Only when the student enrolment numbers grew over the next one year did Daruvala quit his job. “Under-commit and over-deliver — that worked for us,” Daruvala says of those early days.

They would promise students six hours of classes each day, and end up giving eight hours. To this day, Daruvala remembers his heart-felt joy when one of TIME’s first-year students, Usha Swami Seth, got through to XLRI. “Our motto from day one was to take care of the students, and the students would take care of us,” he says.

But even as numbers grew from the 60-odd in the first year to over 500 in the third year — largely through word of mouth — the going was not as easy when it came to the bottomline. TIME lost money in the first two years, and could break even operationally only from the third year onwards.

Flying colours

The year 1995 was a coming of age of sorts. An IRMA graduate was hired as TIME’s first full-time faculty member. A second office in Hyderabad followed. A third partner, M Pramod Kumar, joined the venture the same year, taking charge of expanding the business in and around Kerala. “In a sense, we found our feet that year,” says Daruvala. TIME currently has 200-odd centres spread across 104 cities. Over time, the product portfolio expanded from CAT prep classes to offering coaching for state-level MBA courses, GRE, GMAT, bank, post office, engineering and medical entrance exams.

As the business grew, in 1996, the partners realised the need for training the faculty to maintain the benchmark their students had come to expect. This would enhance the classroom experience for students. “Our training has helped us stay ahead of the curve,” says Asim Akhtar, senior manager, operation, TIME. Currently, the institute employs around 40 IIT/IIM graduates as part of its core faculty and management team.

However, it was only after 1999 that TIME took its first steps to expand through the franchisee route. So that quality is not compromised, Daruvala and his team spend a lot of time with their prospective partners before giving them a go-ahead. Each franchisee typically signs up for a three-year licence fee of Rs.1.5-2 crore. As part of the revenue-sharing arrangement, 15% of gross collection by a franchisee goes to TIME, which also offers the course material. Typically, it takes up to three years for each centre to break even. Of the 200-odd centres, almost 85% are run by franchisees, and the rest are either owned by TIME or operated through a joint venture.

“A key criterion we use is to evaluate whether a prospective franchisee has teaching experience,” points out Daruvala. Today, around 80% of the centre directors regularly spend time with students in the classroom. “There is more to this business than just topline and bottomline,” says Ulhas Vairagkar, director, TIME (Delhi-NCR). “It is the love for teaching and the ability to make a difference in a student’s career that keeps us going,” he adds.

Interestingly, 40% of the 160,000 students who come out of TIME each year are from small towns. This is, of course, by design. Of the 104 cities in which TIME has presence, around 80 are in tier 2 and 3 towns such as Panipat, Bhilai, Amaravati and Palakkad. “The hunger for success and the appetite for hard work is more evident in students from small towns than metros,” vouches Daruvala. The bulk of TIME’s centres are in Andhra Pradesh and Kerala.

Branching out

The rapid expansion over the course of the last decade had a visible impact on TIME’s topline. The brand’s gross revenue jumped from Rs.5.5 crore in FY01 to Rs.106 crore by FY07. “As the product portfolio expanded, it helped franchisees grow their business beyond just MBA-coaching preparation,” points out partner Kumar. A Rs.40-crore fund infusion from Tiger Global through the private equity route in 2008, and internal accruals, helped TIME diversify into the fast-growing preschool and K-12 segment. The deal gave the institute a reported valuation of around Rs.300 crore during the time of the PE deal. Daruvala, however, refuses to comment on the current valuation of his institute.

Currently, there are 67 TIME Kids preschools across six states — Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Gujarat. Two CBSE-affiliated co-ed senior secondary schools operate out of Hyderabad. There are plans to invest up to Rs.40 crore over the next couple of years in the K-12 and preschool venture, and take the preschool numbers to 100. In 2011, the institute also ventured into the English training space when it acquired Chennai-based Veta, which has around 250 centres, mostly in the south. “Teaching English through the vernacular medium is the next big thing in the vocational space,” says Daruvala confidently. The plan is to double Veta’s presence over the next two years and create a presence in the north.

Since FY08, TIME’s revenues have grown from Rs.64 crore to Rs.220 crore in FY12. Though the management refused to reveal the bottomline growth, data from Ace Equity, a market research firm, shows that the institute had clocked a profit of Rs.16 crore in FY10.

Today, the coaching or tutorial business contributes the bulk of TIME’s revenues (around 85%) while 10% comes from the vocational vertical (essentially Veta); preschools and schools account for the rest.

Daruvala expects the share of schools and preschools to be the fastest-growing segment in the next few years. Not surprising, that the partners want to develop a deeper management bandwidth over the next couple of years as they prepare the organisation for its next phase of growth in the K-12 and vocational space.

“At some point of time, we want to make the founders redundant and let professionals run the organisation,” declares Daruvala. Perhaps then he will get more time on his hand to go back to his first love — teaching.