Unlike its peers, which are reeling under pressure because of high debt, government-owned aluminium major National Aluminium Company (Nalco) is a little relaxed, sitting on cash of over Rs.5,300 crore, or 53% of its market capitalisation. Cash gives you a lifeline when markets turn bad, and the aluminium market has been hit by a downcycle over the past five years. While prices have recovered of late to the current level of around $1,600 a tonne from the low of $1,460 a tonne in November 2015, they are still down 70% compared with the peak of $2,700 per tonne in April 2011.

But thankfully, among industrial metals, aluminium prices have corrected the least. Slowdown in consumption in China has resulted in dumping of surplus Chinese production in the international market, leading to a steep fall in metal prices. In the case of aluminium, global production has crossed consumption by 2.6%, creating a surplus of roughly 1.4 million tonne in 2015. At present, aluminium prices are moving in a narrow band of around $1,500 per tonne, much below the cost of production. “70% of companies around the world have reported cash losses. Many smelters have closed down and many more are resorting to production cuts,” said Tapan Kumar Chand, CMD, Nalco, in a statement.

Other metals have been hit in a much worse way. “Non-ferrous metals like copper have seen a higher correction in prices because of their industrial application. The correction in zinc (used in steel making) prices has more to do with the downward cycle in the steel industry. In fact, we expect global aluminium prices to recover FY16 onwards because of the supply cut in the US and China and expectation of improvement in demand,” says Abhisar Jain, analyst at Centrum Broking.

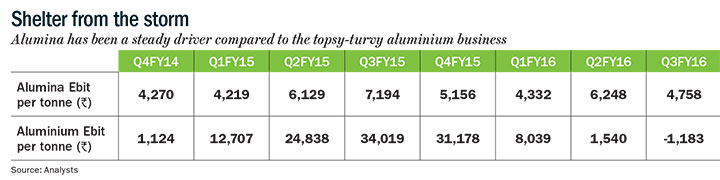

In the commodities business, when the downturn hits and prices come tumbling down, the survivors are the ones with the lowest costs. That’s what works in Nalco’s favour at this point. With capacity shutting down in China, Nalco has been riding the advantage of being one of the lowest-cost alumina producers in the world. To put things in perspective, consider this: at the current aluminium price, the company’s aluminium business, which accounts for close to 50% of its sales, is making losses. In Q3FY16, on a sales turnover of Rs.1,122 crore, the aluminium business incurred an Ebit loss of Rs.132 crore, which is close to $200 per tonne based on the Q3 aluminium production of 96,000 tonne. However, thanks to alumina, which is a refined and converted form of bauxite that is melted to produce aluminium, the company has been raking in a profit. Nalco produces close to 1.9 million tonne of alumina annually, which contributes close to 50% of its sales turnover. Despite the price correction, this segment makes an Ebit margin of over 27%. (see: Shelter from the storm) Nalco’s low-cost bauxite mines allow it to produce alumina at less than $200 a tonne compared with current realisation of $274 a tonne.

In the commodities business, when the downturn hits and prices come tumbling down, the survivors are the ones with the lowest costs. That’s what works in Nalco’s favour at this point. With capacity shutting down in China, Nalco has been riding the advantage of being one of the lowest-cost alumina producers in the world. To put things in perspective, consider this: at the current aluminium price, the company’s aluminium business, which accounts for close to 50% of its sales, is making losses. In Q3FY16, on a sales turnover of Rs.1,122 crore, the aluminium business incurred an Ebit loss of Rs.132 crore, which is close to $200 per tonne based on the Q3 aluminium production of 96,000 tonne. However, thanks to alumina, which is a refined and converted form of bauxite that is melted to produce aluminium, the company has been raking in a profit. Nalco produces close to 1.9 million tonne of alumina annually, which contributes close to 50% of its sales turnover. Despite the price correction, this segment makes an Ebit margin of over 27%. (see: Shelter from the storm) Nalco’s low-cost bauxite mines allow it to produce alumina at less than $200 a tonne compared with current realisation of $274 a tonne.

“Nalco operates a fully mechanised bauxite mine in Odisha. This mine is one of the lowest-cost mines in the world (cash cost of $9 a tonne), boasting of 310 million tonne of resources. Because of low-cost bauxite, the alumina production cost also stays low for Nalco at less than $200 a tonne. In the global alumina cost curve, this falls in the first quartile, which is great,” says Goutam Chakraborty, who tracks the company at Emkay Global Financial Services. Even for aluminium, Nalco’s cost of production is comparable to other Indian players such as Balco and Hindalco at roughly $1,700 a tonne. Globally, less than a third of companies boast of a cost of production below $2,000 a tonne, which makes Nalco fairly competitive.

More headway

Despite aluminium prices dipping to 2009 levels and a 74% decline in operating profit, Nalco reported close to 9% operating margin in the third quarter of the current financial year. Also, because of other income of Rs.124 crore earned on cash on the books — especially since there is no interest outgo — it made a 6% net profit and a quarterly profit of close to Rs.100 crore. But for how long can these two factors — alumina and cash — shield the company? Calculations based on Q3FY16 numbers and production figures suggest that the company is still making a quarterly profit before tax of $320 per tonne of aluminium, which is about 22% of its aluminium realisation of $1,494 per tonne in Q3FY16.

In other words, if aluminium prices come down to $1,174 per tonne — or by as much as 22% — from the level seen in the third quarter, Nalco’s profit will be wiped out. In the past twenty years, aluminium prices have not breached that level, except in 1999, when they fell to around $1,180 a tonne from a peak of $1,700 a tonne in August 1997. For Nalco, things look much better in reality. That’s because today, despite the low cost of raw material, if Nalco is unable to make a profit in the aluminium business, it’s only because of disruption in coal supply, which has inflated its energy bill and limited its production ability.

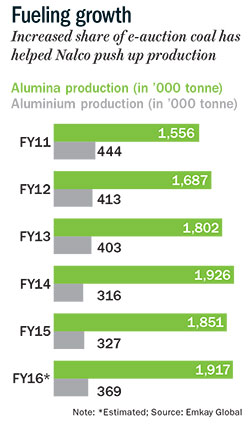

Even during the 2009 commodity crash — when aluminium prices crashed from $3,200 a tonne in early 2008 to $1,450 by April 2009 — Nalco was making close to 50% operating margin. If aluminium prices remain at the current level and the company is able to resolve its other issues, it can rake in more profit. Its coal problem — a remnant of earlier days — is something the Street believes is easing of late, now that supplies from Coal India have increased. “Nalco has been running its smelter at 65-70% utilisation over the past couple of years due to limited availability of assured coal; it restricted its smelter output to the coal available from linkage. But with the improved supply of domestic coal in the past six months, the company has increased its activity in the coal e-auction market. In Q3FY16, it achieved aluminium production of 96,000 tonne, well above the quarterly run rate of 80,000-85,000 tonne in FY14-15, by increasing its share of e-auction coal,” says Sanjay Jain, an analyst who tracks the company at Motilal Oswal. (see: Fueling the growth run) A bigger plus is that it recently got back its de-allocated coal mines, having reserves of 347 million tonne.

Space to grow

To achieve full utilisation, the company requires close to 6 million tonne of coal, whereas it has been getting the raw material in the region of 4 million-4.5 million tonne, thus impacting its production and increasing costs. Since the September 2014 quarter, in which the company’s three coal blocks were de-allocated, the cost of power and fuel as a proportion of sales has gone up, from about 38% back then to 45% in the quarter ending December 2015.

“The higher availability of coal from its own mines will result in substantial cost savings.The company will be able to increase the utilisation of the smelter and thereby improve performance,” says Chakraborty of Emkay. Currently, linkage coal costs Rs.1,600-1,800 a tonne on an average, while e-auction prices have been hovering at around Rs.3,000-3,200 a tonne. Against these rates, we believe that the landed cost of coal from Nalco’s own mines will not cross Rs.1,000 a tonne. Since this will eventually replace e-auction coal, there should be savings of close to Rs.2,000 a tonne of coal for that much quantity. This is likely to bring down coal costs by Rs.500 per tonne of aluminium.”

While better supplies will definitely help the company keep costs down, Nalco is also hoping to produce close to 360,000 tonne of aluminium in FY17, as against the 345,000 tonne projected for FY16 and 327,000 tonne for FY15. Both these factors (higher production and low cost) together should compensate for lower realisations due to falling aluminium prices. Meanwhile, the management has reiterated that it is looking to improve productivity and de-risk its business further by modernising plants to improve efficiencies, brownfield expansion and upstream and downstream integration. It is also planning to diversify into green power, nuclear power, rare metals like titanium, recovery of iron from red mud waste and merchant mining to utilise some of its cash. But then, these grand statements of intent will need the government’s blessings, as the latter may need to draw in dividends from cash-rich public sector companies to plug its own fiscal gap. But Chand strikes a chord of optimism when he says, “We have already formed a JV with Gujarat Alkalies and Chemicals for a caustic soda plant at Dahej. We are also exploring ways to set up a greenfield aluminium smelter abroad, where energy would be available at competitive prices. The company has kicked off discussions with countries like Iran, Oman, Qatar and Indonesia in this regard.”

While better supplies will definitely help the company keep costs down, Nalco is also hoping to produce close to 360,000 tonne of aluminium in FY17, as against the 345,000 tonne projected for FY16 and 327,000 tonne for FY15. Both these factors (higher production and low cost) together should compensate for lower realisations due to falling aluminium prices. Meanwhile, the management has reiterated that it is looking to improve productivity and de-risk its business further by modernising plants to improve efficiencies, brownfield expansion and upstream and downstream integration. It is also planning to diversify into green power, nuclear power, rare metals like titanium, recovery of iron from red mud waste and merchant mining to utilise some of its cash. But then, these grand statements of intent will need the government’s blessings, as the latter may need to draw in dividends from cash-rich public sector companies to plug its own fiscal gap. But Chand strikes a chord of optimism when he says, “We have already formed a JV with Gujarat Alkalies and Chemicals for a caustic soda plant at Dahej. We are also exploring ways to set up a greenfield aluminium smelter abroad, where energy would be available at competitive prices. The company has kicked off discussions with countries like Iran, Oman, Qatar and Indonesia in this regard.”

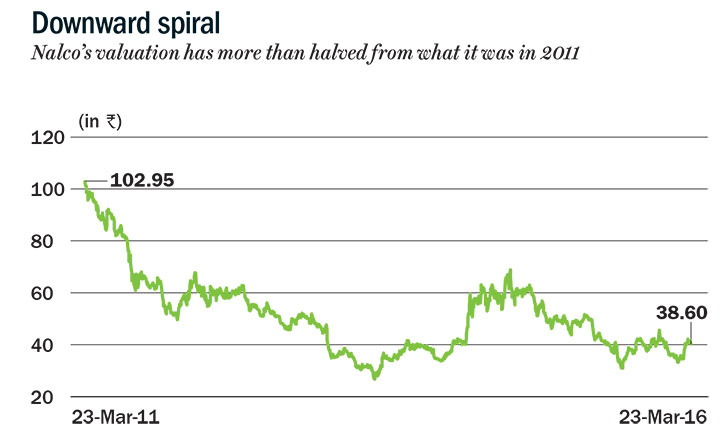

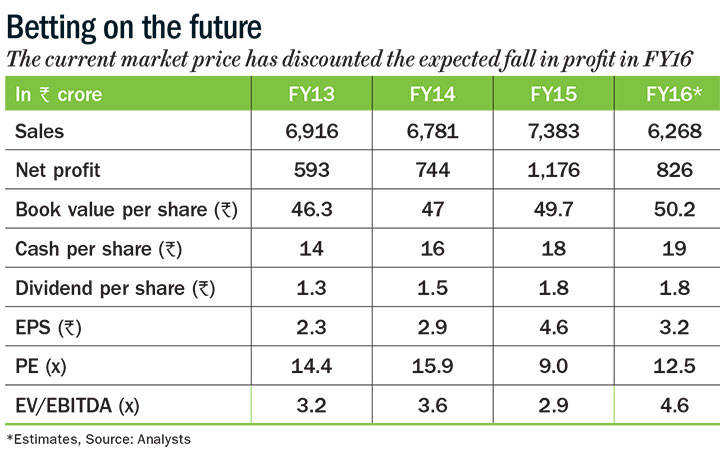

Today, on a conservative basis, even if one does not ascribe much value to the aluminium business, with cash on the books of Rs.5,500 crore (FY16) and a Rs.4,000-crore valuation on the basis of 1x sales or 4x FY15 Ebit for its profit-making alumina business, Nalco’s valuation comes close to Rs.9,500 crore, a little less than its current market capitalisation of Rs.9,948 crore (CMP Rs.38.60). Its loss-making aluminum business, which has a close to Rs.3,600 crore sales turnover, is actually free. On top of that, the dividend yield is 4.5%, which makes the stock attractive.