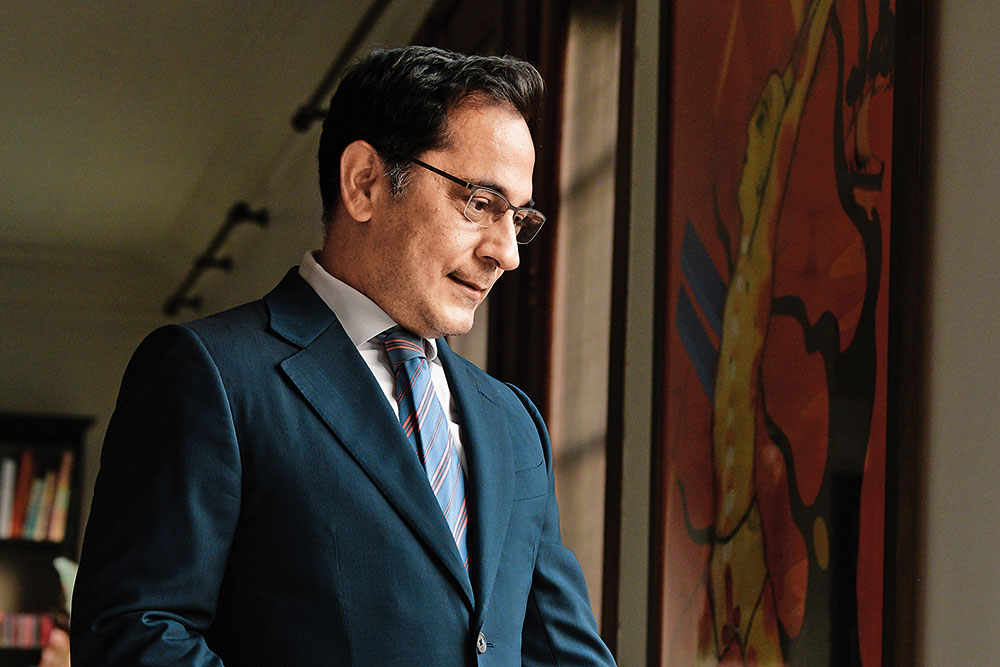

Senior advocate Saurabh Kirpal should have been a high court judge by now, but he continues to hold his clients’ brief before the celebrated benches of the country’s constitutional courts.

Kirpal was officially recommended by the Supreme Court collegium to become a judge in the High Court of Delhi in 2021, though there were reports that the collegium had considered making him the judge on multiple occasions since 2017 but backed down due to the Centre’s perceived objections against him.

Kirpal is not the first candidate who has not found favours with the Central government despite the Supreme Court collegium, which selects candidates for judgeship, endorsing his candidature. However, something stands out in his case.

Kirpal’s is not a case where his track record as a lawyer or his perceived political affiliation has impacted his judgeship. It is more a commentary on the character of Indian polity and society than any direct legal discomfort that the government may have perceived. “Had I already been a judge, it would have showed that the society has reached a level where I do not need to fight anymore. The very fact that it has been delayed on accounts of considerations other than my competence shows that work is needed and we are a conservative society,” says Kirpal. At the same time, he feels that the way his colleagues and the general public have accepted him gives him hope.

Kirpal seems to be paying the price for being open about his sexuality. He is forthcoming about his homosexual orientation and has a Swiss partner. This seems to have shaken the heteronormative foundations of Lutyens’ Delhi.

Media reports suggest that on multiple occasions the government has objected to Kirpal’s candidature for judgeship on account of his partner being a foreign national. It is unlikely that such objections will ever become public records, but people in the legal fraternity, including Kirpal, believe that his not being in the closet makes the government uncomfortable.

The Restless Scholar

While the government takes its time to decide Kirpal’s future, he is using the interregnum to expand his forte of legal scholarship. After his first successful book Sex and the Supreme Court, which predictably revolved around the Supreme Court judgments on the issue of sexuality, he is now out with a book on the legal debates around economic policy, theory and financial jurisprudence. Unlike the earlier anthology, Fifteen Judgments: Cases that Shaped India’s Financial Landscape is as much Kirpal’s independent reflection on society at large through the pivot of law as it is a study of the changing currents around juridical philosophy of the laws that govern businesses and the economy. “This book is not just a legal text about law and commerce. It is a book that mixes history, sociology, politics, economics and the law,” he says. Kirpal suggests that students of law should take interdisciplinary approach, as, he says, “It is a fallacy that a lawyer can be successful without knowing how business works”.

As a scholar, Kirpal has noticed the judicial outlook to the philosophy of economics as it has been practised in the country changing. The expanse of Fifteen Judgments covers this movement from the left to the right rather consciously. He says, “It is not a coincidence that judgments of a certain kind come at certain points in history in India. Why is it in the 1970s, we had left-wing judgments? Why is it that in the 1990s, the judgments start going more right?” The answer, he says, lies in the changing politics of the country that every student of law must study carefully.

The schema of Fifteen Judgments appears to be the culmination of Kirpal’s approach to the legal profession, where he shows an actor’s enthusiasm for each new hat he wears. The amalgamation of themes in the book is how he sees his life as a lawyer, activist and scholar. “One of the most fascinating things about the law is variety. I am not just a one-issue lawyer. I am not a one-issue human being. I do not want to be pigeonholed as ‘that gay lawyer who is not being made a judge’,” he says.

Of Privilege, Hope and Aspiration

Despite the uniformity that a lawyer’s gown seeks to impose, one can easily see the privilege Kirpal is born into. He exudes class and caste in mannerism, the plush house he lives in on the periphery of the Lutyens’ Delhi and the filial setting he is born into—his father B.N. Kirpal was a chief justice of India.

He owns up to the privilege and admits that it has given him an advantage to advance in life and career and be open about his sexuality, something that may not be easily available to first-generation lawyers, especially to those whose families carry lower social standing. “Because I come from privilege, I got a bit of free pass in terms of how people treated me. I do not think I can deny that,” he says, explaining the role his class played in his ability to carry his sexual identity openly.

It is not usual to find a class beneficiary to be caste conscious as well. However, Kirpal acknowledges that caste is as much a factor in his acceptance by the legal fraternity as the factors of class and upbringing when he says, “Definitely because of my caste, class, socio-economic status and geography, I had a set of privileges which allowed me greater freedom which someone who does not have these privileges would not have got.”

Can Saurabh Kirpal become a judicial trope—a metaphor of courage and hard work—in contemporary times who is not a rags-to-riches story but someone who has used his privilege to break the glass ceiling of a heteronormative social order? He certainly thinks so: “I symbolise hope. I represent the aspiration of a large number of queer people in this country to let them know that I am a role model, so that a person from a small-town India can tell her parents, ‘Don’t condemn me for being queer, because, after all, someone holding a high office in our country is also [queer]’.”

The metaphor, however, cannot be realised fully unless the government stops being an impediment in adding sexual diversity to the benches.