Boston/ July 20, 2017

GMO’s co-founder Jeremy Grantham is a market legend with a deep sense of investing history and intense understanding of market psychology. He is driven by numbers and pragmatic as is evident in his quarterly newsletters and during our conversation at GMO’s Rowes Wharf headquarters that overlooks the Boston Marina. He talks with a poise that can only come when you’ve been there, done that. Right now, he is the strongest voice batting for emerging markets exposure, notwithstanding what he eloquently explains as career risk. As composed as he is, Grantham is not bereft of spontaneity. In the middle of the interview he graciously decides to go hunting for the notoriously hard-to-get-in-touch-with James Montier. Grantham jokes, “He will tell you what profound disagreements he has with me because he is an unreformed Ben Grahamite”. John Maynard Keynes is a bigger hero for Grantham as he thinks Keynes was a lot more sophisticated and understood career risk and how the real world acts as opposed to how it should act. With great mirth, Grantham also recalls the morning that he was invited to address the annual Ben Graham breakfast at Columbia University. In his words, “I started it with a quote from Julius Caesar, “Friends, Romans, I come to tease Ben Graham, not to praise him and I teased him for half an hour and had fun pointing out how boring he was.”

In your newsletter you’ve articulated that there is no logical reason for interest rates to go up, primarily because the demographics in the US do not support high demand for capital and the Chinese are saving enough. And considering that we do know that interest rates and stock prices are inextricably linked, why is it that we are not able to reconcile to the fact that our view of stock valuations must change permanently? And if anything, it’s only normal to have multiples at elevated levels. Are value investors victims of anchoring bias at this point?

Yes, I think we are. If you grow up, develop a discipline and immerse yourself in it day and night for 20 years, it’s pretty hard to change your mind. And I think that is one of the problems. It should have occurred to me to take these changes more seriously, sooner. I did pick up pieces of it but I found some excuse not to push them forward enough. Four years ago, in a quarterly letter, I described the bullying of the Fed in the final paragraph that read, “When you consider the power and the influence of the bully and the career risk and the short termism of the bullied — that’s us — it’s easy to see that the bully might win another round or two. And in fact, it’s hard to see this thing ending without the usual signs of a full glorious behavioural bubble.” And then three years ago, I said more confidently, “I don’t think this will end, until the election, and until we have reached a bubble.”

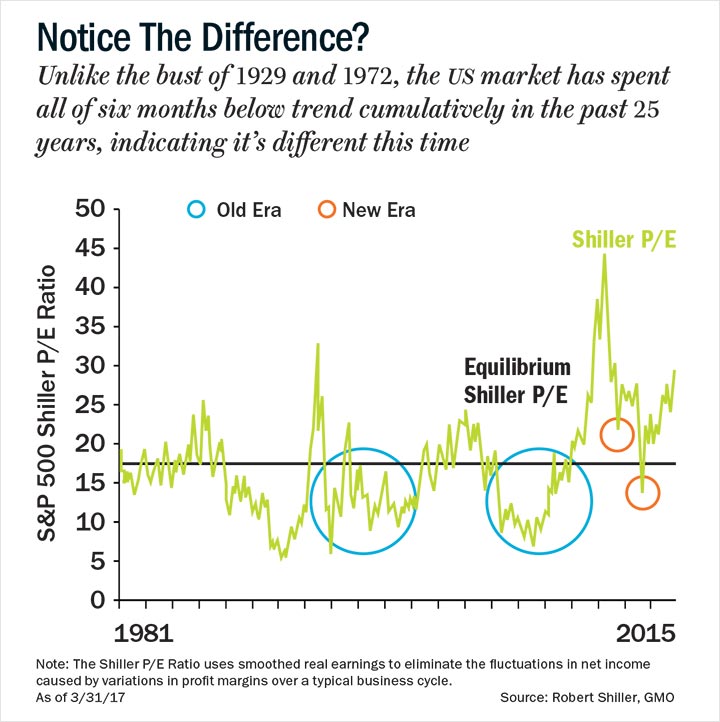

At the time, I made the mistake of defining the bubble in numbers and as it turned out, three years later, the numbers and the psychological manifestations of the bubble had diverged. So, we had the numbers that traditionally would’ve comprised bubble territory, but we had none of the psychological indicators — we didn’t have the credit bubble that we had in 2000 or 1929. We didn’t have the obvious investor euphoria. Interestingly, in 1929, ordinary stocks did not go up, the favourites went up a lot, ordinary stocks were pretty flat and the risky junk, which normally has beta of 1.5 or 1.7 went down a lot. The S&P had an index then called the “low-priced index” and they were down almost 40% before the bubble broke in 1929. In 1972, we had a focused market called the Nifty-Fifty — Avon, IBM, Eastman Kodak, Johnson & Johnson, and when the market peaked, the average stock declined. I remember because the market was up 17 (%), and the average big-board stock was down 17 (%). And in 2000, the advance/decline line peaked out two years before, by the end of 1998. In each of these cases, the advance/decline line declined quite steadily and powerfully, while the market kept going up.

But when you look at the advance/decline line versus the market today, that’s not the case. We have a very broad market that lacks all serious behavioural indicators of a bubble. So it’s not a bubble and therefore one doesn’t expect it to blow up in the way it did in 2000. And yet a lot of value managers looking at the price only say, every time it hits these prices, we get bad times — and it’s correct, we have had it until this time. But now everything has changed. We may still get a bubble but I would wait until I see psychological indicators of the past. That, if you ask me, isn’t going to happen on this side of 3,000 on the S&P.

My latest quarterly letter includes extracts from Ben Graham’s last talks in 1963 and he says, as I do, that the market can always have a bump in the road, it can always have an ordinary bear market. And it can have a serious bear market if something goes terribly wrong, but if it does, it will be the first time in history that it has happened without the normal indicators of excess. So as the all-time high priest of value management, he was making exactly the point that I am making! I describe this letter as heaven-sent as it came out of nowhere and I picked it up couple of weeks before writing my quarterly letter.

Ben Graham says, “In early 1955, when I testified before the Fulbright Committee, the Dow Jones then was about 400. And my estimation of fair value was around 400 and other experts were also about that level. But the action of the stock market since then would appear to demonstrate that these methods of valuation are ultra-conservative and much too low. Although they did work out extremely well through the stock market fluctuations from 1871 to 1954; which is an exceptionally long period of time for a test, unfortunately, in this kind of work, where you are trying to determine relationships based upon past behaviour, the almost invariable experience is that by the time you’ve had a long enough period to give you sufficient confidence in your form of measurement, just then new conditions supersede and the measurement is no longer dependable for the future.” Bingo! Isn’t that wonderful? I’ve been labouring since the fall of last year to make this point that we developed measures of value, which simply do not apply today.

The market has always loved variables that make it feel comfortable and it has them now. The market P/E can be explained — have a correlation of 0.90 — to high-profit margins, low inflation and stability of GDP and when they get these conditions, they will give a high P/E. When they get the reverse, they will give a low P/E.

And it explains the peaks in 1929, profit margins peaked; 2000 they peaked; 1972 they peaked; and inflation was low enough in 1929, little bit higher in 1972 and low enough in 2000. It explains the troughs too. The only outlier to this model is 2000, when the model predicted the highest P/E in history, but the market went one-third higher than that. And that is by far the biggest miss, and that was a genuine bubble where people truly believed the world was different forever and we were on a glorious high plateau, with brilliant productivity as Alan Greenspan used to say.

In 2001, Warren Buffett famously wrote in Fortune about the linkages between stock prices, GDP growth and interest rates. Looking at two periods, from 1964 to 1981, and from 1981 to 1998, he found that even though the GDP growth in the first period was double that of the second, the Dow did not move at all because interest rates went up from 4.2% to 13.65%. In the second period, when the interest rate moved down from 13.6% to 5%, the Dow actually went up 10x. Thereafter, if we look at the period from 1997 till now, interest rates have gone down from 5.2% to almost nothing right now. Extending the same model, will it be correct to say that stock prices today are not only justifiable but incredibly cheap?

It’s hard to say. That model wants to tell you that profit margins are the most important factor, but when you think about profit margins, if they go up, they move the earnings up and they move the P/E up. So Wham! Wham! More importantly, it’s not clear what Warren Buffett was talking about, whether he looked at real rates.

Back in the ‘70s, most of the interest rate was just inflation pass through, but now, we have the real rate, which has gone to zero. You can hardly work out what the real rate was back then, because inflation was bouncing around upto 12% in 1981-82. We know that the inflation component really kills the P/E; what is much harder to estimate is the impact of real rates. The real rate component typically doesn’t matter, but it does today because we have very modest and very stable inflation, so the real rate is much more visible. Everyone can see it’s about zero or less for a T-bill. And that puts its own pressure on investors — do you really want to put your money at -1 in the piggy bank or do you want to take a risk and buy an overpriced, or what appears to be an overpriced stock?

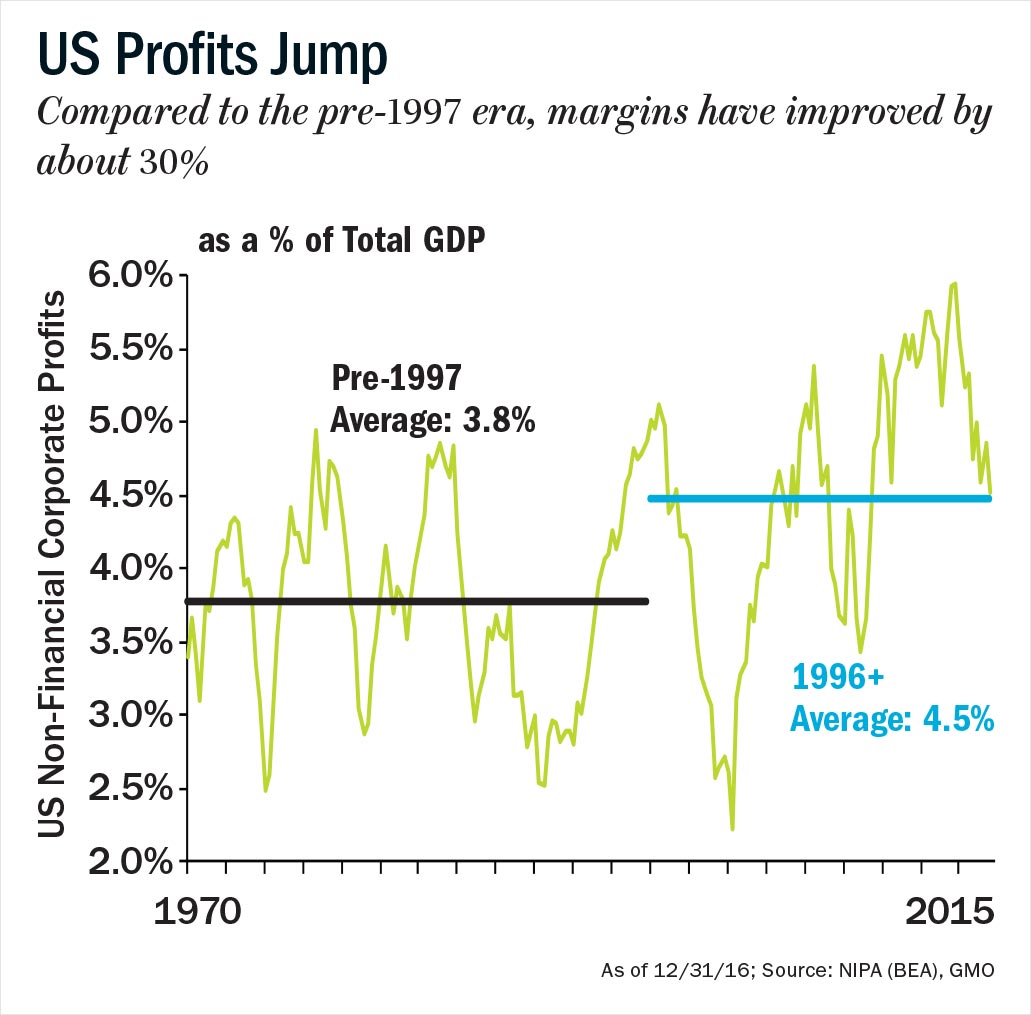

I am pretty convinced that it’s not just the rates. Perhaps, the rates are a very big input in the profit margins. And we ran a little test. Let’s imagine, step one, the real rate on corporate debt was two points higher, like it was forever until 1979. Step two, let’s imagine that the leverage has moved back to where it came from. Those two things together take your profit margins back almost to nought. So profits are up, because leverage has gone up and the cost of debt has gone down. I think therefore, that it’s mainly profit margins but yes, it may be influenced a lot by interest rates. The Wall Street Journal, the week before last, worked out global GDP volatility, it was the lowest month in the 40 years for which they had data. Absolutely dead low. So, incredible low volatility, high profit margins — not peak, but still very high — and very low inflation; even below the level that the Fed would like. Check, check, check. You’re going to have a high P/E! Don’t tell me it’s high-priced. Now, why is the price so high? That’s because for 20 years you averaged high-profit margins, low inflation and high level of stability in GDP. Capitalism is meant to drive down high-profit margins, they are meant to be cyclical, and not stay up for 20 years. That’s unusual.

Similarly, earlier, GDP would spike up and then head down, but this time we’ve had it for 20 long years. The average P/E for the 20-year block is higher than that in ‘29, ‘72 and ’87 when it went above 21. And for the entire 20 years, P/E has averaged 23. I mean, that you have to admit is different, but it’s all explained behaviourally by high-profit margins and low inflation. Now you have to explain, why are profit margins so high? Partly, it is low rates and high leverage and perhaps, there are other factors involved, it’s hard to know which mix of factors. My favourite reasoning is that American corporations are provably more monopolistic, their industry concentration has provably gone up a lot, number of companies in existence has actually halved, the number of people employed in new enterprises i.e. one- or two-years-old has halved, so capitalism is on a bit of a down leg, it is not very virile. But monopolies are looking pretty good.

The Justice Department has gone to sleep — it has allowed mega deals to go through and the political power of American corporations is so great that they get exactly what they want. So, that should make for a world where they acquire the institutions designed to regulate them, full of people from corporations: the drug regulators are old drug managers, the energy regulator has all fossil fuel guys. Industries own the regulators, they design regulations, not to help all the companies, but to help big ones, the establishment. So they should have higher and stickier profits than normal, which is what they have. Low rates, high leverage, high monopoly power and then globalisation of brands, have benefited corporations. It’s all an American advantage, so American corporations should have higher profit margins than anyone else.

How fast is the situation going to go away? I would say it will mean revert because we the people will push back sooner or later, won’t we? We may vote out the corporate types like Trump and vote in an anti-corporate type like Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders, but even then the wheels will move very slowly. The pendulum has swung for 20/30/40 years in favour of corporations and all we can hope for is a moderate swing back over 20/30/40 years. So, people who are expecting the traditional rapid mean reversion may have to hold their breath for a long time. It will happen eventually, but will prove to be rather slow.

And what about the mean reversion of interest rates? For that you have to get into the problem and explain why interest rates are low. And there are a dozen theories, my favourite being the Fed policy, the ageing profile and the odd fact that China saves so much. So you have three reasons pushing down interest rates. Are they going to change fast? All this will be like watching grass grow. It can change a lot in 20 years but it cannot change that much in seven.

So, where does that leave you as an investor? Would you be more confident investing in stocks that are thought to be overpriced but we have reasons to explain why they are priced the way they are, or be sceptical because as a value investor you always like to err on the side of caution?

That is my next quarterly letter! Unless my colleagues talk me out of it, it is going to be called Career Risk and Stalin’s Pension Fund. And the subtitle is ‘Investing in an era of higher priced assets’. So what do you do? There is a very strong case for emphasising asset classes over individual stocks. The development of exchange-traded funds and indexes causes a broad ripple across the entire market place. The career risk of picking one insurance stock against another is pretty low but it’s huge picking cash against stocks or emerging markets against US blue chips.

The opportunity today is indeed emerging. And the only reason you should not have 40/50/60% in emerging is career risk. You don’t want to look too unusual. It’s not how you prosper in the business or your own personal career. But it would be the best chance that your pensioners have of making a decent return; an ordinary, diversified portfolio would be lucky to get 2% real in the next two years, and 3 (%) would be an outlier. But you’d have an 80% chance of staying alive in emerging markets — it is a nice broad index with 28 countries, some of them are growing very fast. Growth rate of the developed world has slowed way down and it will stay slow in my opinion.

In the second place, I’d put EAFE (developed countries ex-US), and in a distant third, I’d put the US. I am getting a lot of grief because I am saying the US is not necessarily going to have a major league collapse, hence the newsletter title is Not With A Bang But A Whimper — so it just whimpers off to the distant future, killing the pension fund, without allowing a readjustment opportunity. What would be glorious for asset allocators is that the market would drop 50% in the next year or two allowing us to take all our cash and buy cheap stocks. I don’t think that is very likely, unfortunately, I would love it, but it doesn’t seem likely for the reasons we started with.

You are bullish on the emerging market equities, and you think that might be a place to go if you need to keep your outperformance?

No, if you just want decent returns.

So what makes you bullish about emerging markets? Today, if we look at “growth” opportunities in India, we find that most consumer companies that boast a high RoE trade at 50x earnings, and as opposed to that we find American corporations with fairly high RoE with significantly higher scale, monopolistic characteristics, and opportunity to globalise like Apple, Google, P&G, Disney and so many others, trading at less than 15-20x earnings. Are you saying that India’s growth is better than America’s moats?

Well, you’re not really saying Indian equities; you’re saying Indian growth stocks. If you look at the P/E of the entire marketplace, you have a lot of more boring, ordinary, cheaper companies. And maybe that’s where the real value of the Indian index is. You are describing the 50% RoE with low leverage, which would be pretty nice, at any P/E almost. So I’m not quite sure why you would have a 50 P/E and find American companies superior. Apple has a high return but doesn’t have a 50% RoE.

I have no axe to grind for growth companies in particular. I’m only saying that, collectively, the US market is much higher priced than the collective emerging market. You can have much more confidence in an aggregate statement than you can in an individual one. For example, if you measure the return of an entire industry and it seems to be cheap, that is a much stronger number than having one or two companies that seem to be cheap and others that seem to be expensive. Perhaps they are cheap for a good reason, perhaps you’re making a mistake. But when you are looking at the whole industry, the chance of a mistake goes down — if the whole country looks cheap, there is even less chance. So, I look across the entire emerging market universe. I’ve got great confidence that those numbers are correct.

There are a few things that worry me about the American companies you mentioned. When I look at Apple, I don’t know if its next iPhone will be a total bust. It’s a consumer company with over 50% profit dependent on one single product. If that goes wrong, that could be a total bust. If there is a disaster in China where they assemble iPhones, or if it’s proven that using those handsets give you cancer...

The other point that worries me is that the internet is generating incredible price disclosure, so doesn’t that threaten brands? So for any product you can find the cheapest item in the world. And who cares what the brand is, and then Amazon starts to make them itself and you get a consumer rating on them and pretty soon Colgate no longer matters, you can get Amazon toothpaste with three-star ratings from consumer reports, delivered to you tomorrow, a one-year supply, much cheaper and convenient along with your other orders. So there are some pretty big threats lurking around some of the great franchises. Coca-Cola, sugar kills you! The rate of change is so high that you can’t possibly have that much confidence.

So I’m not trying to plug growth companies at all. I suspect that from here on value companies will do much better, growth has had a very good run since the crash in 2009, they’ve won most of the years. Having said that, I can’t resist saying that I think the fundamental rate of regression has slowed a bit. The main driver of an American corporation used to be market share, so if paper got tight, then every paper company would have a new paper mill and they would crush the giant profits. They would have one good year of profits and then three bad years. Now they don’t do that, they’re very tight with their expansion and they use the cash flow of these high-profit margins to buy their stock back — it’s very safe. You buy your own stock back, you get rid of the pessimists. You tend to push the price up, that’s great for your stock options and that’s what we’re doing, $600 billion a year of stock buybacks, which is bad for growth, bad for jobs, but great for profit margins and great for corporate offices and great for stockholders.

What’s your view on commodities? If we are assuming a lower level of global growth over the next few years, then the case for commodities might just be very weak.

Commodities don’t thrive based on the rate of growth, but on the rate of growth relative to expectations. So if everyone thinks and knows that growth is slowing, then they can do okay. If the world were to pick up unexpectedly, they should do very well because they have spent the past five years acclimatising to low growth, and a pleasant surprise would make them a lot of money and they’d turn out to be the group to own. Now the question is, what are the chances? The great bust came because China stopped on a dime much faster than anyone had stopped before. Iron ore, they were growing double digit per year. And then bang! They didn’t go 9, 8, 7, 6, which would be bad enough, but they went +11, 0, 0, 0 and for three years there was no growth at all. Same for coal. Unprecedented, China is 50% of both markets and stopping like that crushed both markets.

As for oil, it is much more volatile than people realise, the normal volatility around the trend line is more than a double and less than a half — that’s normal. So if the trend line is 16, it goes to 35 or 7 and that’s normal. Overall, my guess is that they (producers) are spending much less, they’re finding much less, and what they’re dealing with is the shock of US fracking. The big question is how much high grade, low-cost fracking do they have and I think a consensus would be about two years of supply for the whole world. But it’s on the margin so it buries the price for a while, and how quickly they run out of the really cheap stuff.

According to the The Wall Street Journal, the 20 main frackers have not made any positive cash flow, since the beginning of the game including last year. They are spending more than they are generating and they are doing it because of their ability to sell stock on the market and raise debt money from an easy-going, friendly stock and bond market, even though they are not justifying it, even though they are doing it at a loss. Eventually, that will change. It will be revealed that you simply can’t make a decent return at less than — and then you fill in the magic number — 60 bucks. And that’s simply not enough. Even at that price you can’t keep feeding the world and so the price will spike up. My guess is sometime in the next few years, the oil industry has one last good spike before the arrival of the electric car.

What do you think will be the effect of what The Economist once described as the generational challenge? The fact that with the ageing population the pension funds will be net sellers in the market. Since the ‘70s, the large inflows and demand for equity assets from defined contribution plans kept markets buoyant, but now the net accruals will be lower or negative putting them on the selling side.

If you look at the whole world on an aggregate basis, the top-down analysis would indicate that the pool of savings should continue to rise. Outside America, India and the places like that in the world have a different age profile and they will all be saving away as ferociously as they can. The problem comes from the fact that the US and the developed markets are a big chunk. My guess is that it is probably not a determining factor, but if the US existed on its own, you do get a logic that implies pressure on assets. It’s similar to the argument put forth by Rob Arnott that as more retirees are selling houses and fewer young people are buying them, American house prices would come down. But we are at a time where the baby boom is busting out, but we see shortage of land in desirable cities. San Francisco, Boston are seeing prices rise, so are several other cities albeit at slower rates. There is no sign of this changing, even though the population profile is begging for it, so there seem to be other factors at play.

Could that be one of the prime supporting reasons for the Fed to actually pursue a policy to continue to keep asset prices at elevated levels? Because there are these really large macro challenges at hand...

Well, if you think that’s a problem, think of the Bank of England. It has a housing market that in 1998, when my sister bought a house, was just under 4x family income, which was at the lowest point in 50 years. Now, it’s 10x family income and floating rate mortgages is not tax deductible. Same with Sydney, another classic city. So let us move the rate back to seven from three now, and by the way it’s been at 15 in London, at 10x family income, it takes 70% of your pre-tax income to service your mortgage. The Bank of England guy knows that’s a disaster, he cannot have the mortgage go back to seven, which 10 years ago would’ve historically seemed quite ordinary, but today, he would wake up in the middle of the night shivering at the thought that could happen because the housing market is huge in England. It would crack the housing market, bankrupt some banks, and ruin the economy for quite a while. It doesn’t matter if it is inflation-driven or whether the real rates go up or some combination thereof, but just getting to seven floating rate could mean death. That’s much worse than the US. We have fixed rates, we’re locked up at a rate we can afford, and house prices are edging towards 5x family income. I mean this is paradise compared to the UK.

Anyway, I’m agreeing with you, it’s a real problem, it may be a catalyst. The London housing market and a handful of others around the world may be the catalysts for the next bust, because they are bubbles.

How would you have viewed margin of safety 10 years ago and how you would look at it today? Can you demonstrate that with an example?

In 1974, at the bottom of the market — it got to 7x earnings — we wouldn’t consider a stock for our portfolio unless it had a 10% yield. There were a handful of companies that had a 10% yield, so why not pick the best ones, the biggest ones? The equivalent of that today would be a 4% yield, I guess. You would have to hunt high and low to get a 4% yield. What an amazing difference that is!

One of the features of technology companies such as Microsoft, Apple, Google is that the market just tips, and the whole characteristic of winner-takes-it-all comes into play at a certain stage. These technology businesses tend to be monopolistic rather than oligopolistic like retailers, cable television or several other consumer segments. Does that mean that there is a case for paying up for their earnings?

There is a case for paying up for their book but not for their earnings. P/E is already giving you full credit for that extra profitability. Let’s assume you are paying 20x for both of these low-return and high-return companies. To take the pure example, you pay everything out as a dividend and you keep nothing, so there is no growth. At 20x earning, both give you 5% yield, agreed? Forever. So that makes it comprehensible why you would have the same P/E, even for a higher return company, but not the same book or price to asset.

Are we closer to a turning point in terms of the broader market? Many seem to be abandoning the tried and tested value investing approach and moving over to momentum or passive investing.

This could be the foothills of something interesting. To make this market really exuberant and ready for a bust will take considerably higher prices but we could get there in 18 months at the current rate. That would take us over 3,000 on the S&P, but the proof is not the price, the proof is in the behaviour. Things you can measure — are people getting ecstatic? Are people dumping their value stocks and hiring growth funds or are they piling into Amazon and Apple, not at the current rate but at a magnificent accelerated rate. Does the market start to look hyperbolic? More and more concentrated, more and more rapid increases, more and more enthusiasm... the market today has hit a new high, but we don’t hear it on the radio, on the TV, or in the newspapers, it was a new high yesterday, new high is every day, but no noise.

Back in 2000, every day they jumped up and down, rang bells and had a party every day. So it’s got a long way to go if you want to have a classic bubble and a market break. But I have learnt, let the facts speak for themselves. We reverse engineered the numbers, we went back to all the great bubbles in history and said what was the price, and just to make it convenient, we said we’ll use that as the definition of a bubble, which enabled us to go through every asset through all of time. We ended up with like 300 bubbles to study. But that was just convenient; the real definition of a bubble should be extreme, emotional behaviour. We are not yet there.

Having been an investor for 50 years now, have you come to believe that history is no longer a reliable guide when it comes to investing?

(Laughs) I am absolutely certain, it is not a reliable guide. It may be a semi-decent guide much of the time, but it is not reliable. That’s the key, you can’t treat these things as cast iron rules, I’d suggest aluminium rules, a little bendy. There are a lot of handy rules and they mostly work, but none of them are absolutely reliable...

...except margin of safety?

A margin of safety is a self-referential statement. If it didn’t work, there wasn’t one, so you’re defining success when you say margin of safety and you can’t argue with that. Winning is always a good idea.