When the skies opened up on December 4, 2023 in Chennai, industrial operations in the neighbourhood of Ambattur decided to call it a day. Before long, water had entered industrial units housing high-value machines. Lakes in the region started to overflow. Run off from two areas—Avadi and Poonamalle—had added to the overflow, it was later determined.

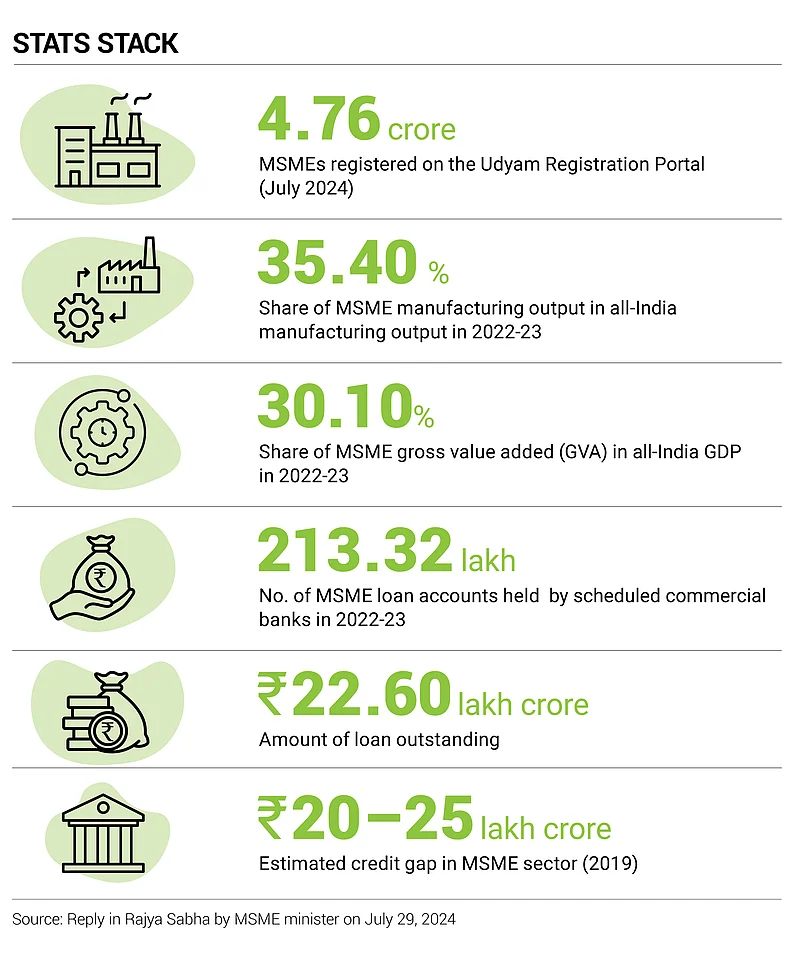

Ambattur is the largest small-scale industrial estate in South Asia. As Chennai and its adjoining districts went under water, so did units that were home to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Losses to the sector were estimated to be over Rs 7,000 crore. Once the rains subsided, the Chennai Municipal Corporation reportedly said the city had not seen a similar downpour in close to 50 years.

The unequal impact of the climate crisis is becoming increasingly visible on industrial operations and workers. In the Chennai floods of 2015, the MSME sector lost over Rs 1,700 crore due to disruption in production. Eight years later, Cyclone Michaung amplified those losses in the city many times over.

The Case for Aid

Small producers and manufacturers are on the frontlines of the battle against climate change, often bearing the brunt of extreme weather events that disrupt their operations and the value chain. Climate-proofing these systems is critical, but the issue of climate finance to the Global South remains the elephant in the room.

Billed as the ‘finance COP’, the next UN climate conference, COP29, is taking place in Azerbaijan’s capital Baku from November 11–22. It is expected to iron out differences related to climate finance flows between developing and developed countries even as these differences continued to weigh down conversations at recent pre-COP negotiations.

In a speech to delegates at the negotiation, Ilham Aliyer, president of Azerbaijan said, “As we are entering into the final stage of preparations for the COP29, I call on you to engage constructively and in good faith for the sake of humanity…We cannot afford to waste time on defining who is guilty of global warming, or who caused more environmental harm.”

Geopolitical instability in West Asia and the shadow of the US presidential elections on the Baku negotiations may see concrete outcomes pushed to the next COP

Baku is expected to bring some clarity on what constitutes climate finance and from what sources, by arriving at a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) to meet the climate funding requirements of developing countries beyond the 2020 period.

India has already submitted a proposal to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change for developed countries to provide at least $1trn per year in climate finance to developing countries from 2025, composed primarily of grants and concessional finance to act on global warming.

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are, indeed, a focus area for action at COP29. The UN climate change high-level champion for COP29 Azerbaijan, Nigar Arpadarai, has launched the ‘climate-proofing SMEs’ campaign to enable SMEs to take climate action. The campaign hopes to build capacity through increasing SME access to resources, showcase SME-led climate leadership and enhance collaborations by calling on large organisations to support SMEs in value chains.

The COP29 champion has another initiative lined up for MSMEs: one that finds change- and impact-makers, focusing on leaders and innovators in small business. The non-profit SME Climate Hub is also signing up SMEs for climate action. The first step is making the commitment to halve emissions by 2030 and become net zero by 2050 or sooner. In return, SMEs—307 from India have signed up—get resources tailored to support them on their net zero journey.

But a pet peeve of the cohort of the Global South is that while the need for climate finance has increased multifold, the Global North has not kept its earlier promise of $100bn investments per year till 2020 to mitigate the impact of global warming. For India to meet its net zero targets, for example, massive investments are required, expected to be in the range of $7.2–$12.1trn by 2050.

Show Me the Money

Vivek Sen, India director for Climate Policy Initiative, a global non-profit research and advisory institution, does not expect the long-standing issues around climate finance to get resolved anytime soon, and certainly not in Baku. “Baku is expected to deliver more commitments than results on climate finance, including the ambitious goal of setting a new global climate finance goal for the post-2030 period,” says Sen.

Developed countries classify finance flows to any climate investment from any place as climate finance while developing countries look at climate finance as aid through grants or at a concessional rate of interest. “The gap is too wide to be bridged through negotiations,” says Dhruba Purkayastha, director, growth and institutional advancement at the think tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

The global stocktake at COP28 had highlighted the significant gap between current climate finance flows and the needs of developing countries. Experts said it is likely that developing countries increase pressure on developed countries to get more ambitious commitments.

Climate finance experts added that COP29 could see the development of new funding mechanisms, such as climate investment funds or debt-for-climate swaps to increase the availability of climate finance. But to qualify as the ‘finance COP’, the event needs to facilitate creative solutions on the finance side, including those coming from the private sector, says Sen.

An Elusive Carbon Market

The other key issue is the setting up of a global carbon trading framework. Pointing out that India is in support of global carbon pricing, representatives of Indian industry have been advocating for more predictable and transparent carbon markets that would help businesses align with global climate goals and maintain competitiveness.

In fact, SME participation in the carbon market can encourage these units to explore energy-efficient practices that cut costs and minimise compliance-related risks in a regulatory landscape that is continually evolving. Setting up a global carbon trading framework has been in the works since the Paris Agreement of 2015. Negotiators are expected to conclude these discussions in Baku.

“The voluntary carbon market has been growing globally for the past couple of years. With better integrity and a stable framework, the market has the potential to be further stimulated,” says Manish Dabkara, chief executive, EKI Energy Services, and president, Carbon Markets Association of India. Linking carbon markets and allowing the use of carbon credits to offset emissions will create a more efficient and effective global carbon market, he added.

However, despite the growing weight of expectations from Baku, geopolitical instability in Europe and West Asia and the looming shadow of the US presidential elections on the negotiations may see concrete outcomes getting pushed to the next COP in Brazil in 2025, say experts.

If a global framework for carbon trading takes shape, Indian businesses will benefit from increased access to international carbon markets. “They will be able to sell carbon credits generated through their emission reduction efforts, which will translate into additional revenue streams and incentivisation of investments in sustainable business practices,” says Dabkara.

What MSMEs Want

As far as India is concerned, MSMEs require targeted support to address climate risks. Access to climate finance and adaptation strategies are vital for these businesses to build resilience against future climate challenges.

The crucial aspects of COP29 are going to be how climate finance and carbon markets negotiations shape up. “Both need to be resolved if we want to have faith in COP,” says Mahendra Singhi, director and strategic adviser, Dalmia Cement (Bharat).

Corporate India has high expectations from COP29, particularly when it comes to addressing climate finance gaps through the NCQG and Article 6, says Seema Arora, deputy director general, Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). “Indian businesses seek more than just setting and meeting the NCQG target—they require better financial instruments and streamlined access to international climate finance to drive adoption of low-carbon technologies, implement resilience projects and accelerate clean energy initiatives,” she adds.

India’s concern also extends to the implications of measures such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which levies a tariff on carbon-intensive products that are imported to the European Union but can be a major challenge for MSMEs that have limited capacity and technical constraints to conduct such an exercise.

In this climate of uncertainty, what are the next steps businesses can take? “Industry is looking for creative solutions to unlock climate finance. This includes resolving issues around the NCQG, which has been contentious,” says Rambabu Paravastu, chief sustainability officer at Greenko Group, and co-chair of Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry’s (Ficci) climate change sub-committee.

Indian businesses are cognisant of the needs of the new paradigm of green competitiveness, says Purkayastha. He adds: “Corporate India views climate action more as an opportunity than a regulatory burden.” In the meantime, industry chambers, like CII, Ficci and Assocham are cobbling together a delegation of Indian businesses to visit Baku.

However, experts at a recent pre-COP discussion in Delhi suggested India may need to mobilise most of its climate finance domestically, by leveraging the private sector and pushing for reforms at multilateral development banks for better funding terms. That’s preparing for the worst—till then, all eyes will be on the Baku negotiations.