A spectre is haunting Indian manufacturing. The spectre of industrial unrest.

On September 9, more than a thousand workers at the Samsung plant near Chennai downed their tools to protest stagnating wages in what is being called one of the biggest industrial unrests in India in over a decade. Located in Sriperumbudur, around an hour’s drive from the Tamil Nadu capital, the plant accounts for a third of Samsung’s India revenue. The workers say their wages have not kept pace with the rising cost of living in one of India’s most prosperous states. Samsung says it pays its workers twice as much as other companies in the region.

Thirty-seven days later, the strike ended. Yet, the imbroglio has wide ramifications. Both the Centre and governments in states have been bending over backwards to woo electronics manufacturers around the world to come to India and set up manufacturing plants. At the moment Samsung workers in Tamil Nadu stopped work, the state’s chief minister, MK Stalin, was in the US talking to companies about how friendly his state is to foreign investors. The Narendra Modi-led government at the Centre is wary too. A big enough industrial unrest can derail the government’s flagship Make in India campaign.

The past decade has seen India make significant changes to its labour law framework, changes that the forces of global capital have called reform and workers and trade unions have called systematic disenfranchisement. On September 25, when Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) celebrated 10 years of the Make in India initiative, workers and trade unions took to the streets in Delhi, Lucknow and Kolkata to protest against changes to labour laws.

Reason for Rage

At the heart of this recent flare up in one of the world’s fastest-growing major economies is the rising cost of living. Erratic monsoons, heat waves and frequent extreme weather events are making inflation, especially food prices, volatile and unpredictable, putting a squeeze on kitchens in millions of households.

Food inflation in India has been at over 6% between June 2020 and June 2024. Six out of 12 food categories have seen 6%-plus inflation for most of this period. Food inflation in the past four years has averaged around 6.3%, much higher than the 2.9% average recorded between 2016 and 2020.

A recent paper by Reserve Bank of India (RBI) deputy governor Michael Debabrata Patra and others observed: “High food inflation is influencing households’ inflation perceptions and expectations with potential spillovers into non-food prices.” They noted that food inflation has become endemic since 2020 fuelling widespread anxiety. These anxieties are doubled by wage growth happening at a snail’s pace.

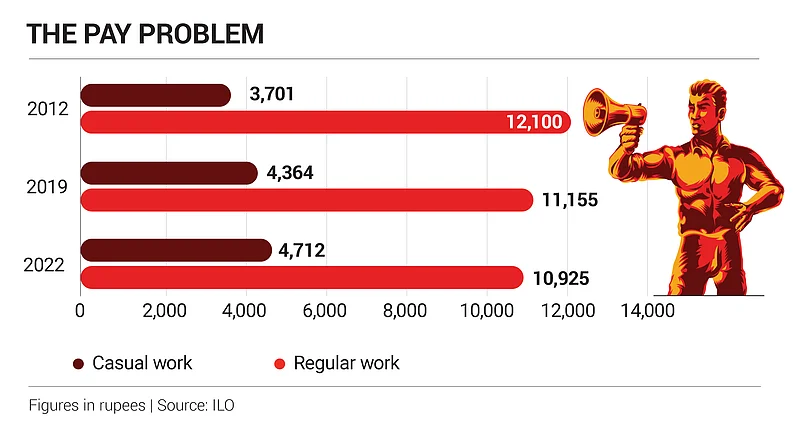

Workers in India’s manufacturing sector anyway earn less than their counterparts in other sectors. Add to that, average wages per worker growth between financial years 2020 and 2023 has been a modest 5%. This is despite the fact that industrial output in the country has seen a significant uptick.

Never mind the workers, even the Centre seems a little miffed with companies for not raising their investments. The Modi government, over the years, has spent millions on infrastructure and granted sizeable tax sops to India’s corporate sector in the hopes of addressing investment and employment-related issues.

Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman pointed this out in 2022 when she asked business leaders why they were hesitant to invest even after the Centre lowered taxes. Just three years prior, the government had slashed corporate tax rates from 30% to 22% for existing companies and 25% to 15% for new manufacturers.

India’s chief economic adviser (CEA) V Anantha Nageswaran made a note of this in the 2023–24 Economic Survey where he said that the current proportion of private sector investment is not enough to raise the share of manufacturing in the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and may create only a few well-paying jobs.

Despite swimming in profits, Indian businesses have not responded to the government’s call for investment. Financial results of a sample of over 33,000 companies show that profit before taxes nearly quadrupled between the financial years 2020 and 2023, according to the Economic Survey. “Hiring and compensation growth [have] hardly kept up,” the CEA noted.

“During the recovery phase post the pandemic, businesses focused on becoming leaner. Hence, there was cost-cutting and increased digitisation. These changes have helped profit margins, especially in sectors such as technology, finance and fast-moving consumer goods [FMCG]. But these did not translate to an increase in wages for workers,” says Manikandan SM, chief business officer at Aparajitha, a labour compliance solutions provider.

Manikandan adds that India has a large informal labour market which leads to minimal job security and bargaining power. “In recent years, even formal employers have turned to short-term contract employment instead of hiring full-time staff. In this arrangement, workers do not see regular pay raises unlike those in traditional jobs,” he says.

Cheap Labour As USP

For decades, companies that have set up manufacturing plants in India have done so because of cheap labour costs. In 2022, India was ranked as the country with the lowest manufacturing costs globally by the US News and World Report. Despite this, the manufacturing sector’s contribution to the GDP remains a meagre 17%. In contrast, countries like Vietnam and Mexico—two major beneficiaries of the China Plus One strategy—have manufacturing account for over 20% of their GDPs. Workers at factories in Vietnam and Mexico also enjoy better pay.

This is primarily because Indian manufacturing has a productivity problem. An analysis of the KLEMS (capital, labour, energy, material and service) database by RBI reveals that labour productivity contracted in nine out of 27 industries in 2022–23 compared to the previous year. Eight of these industries were from the manufacturing sector.

The Centre is trying to solve the low productivity problem by upgrading industrial training institutes (ITIs). The Union Budget for 2024–25 announced the upgrade of 1,000 ITIs. But whether such moves will aid the manufacturing sector, which already employs 1.84 crore people, is debatable.

“Frontline manufacturing roles, often focused on support and assembly, are considered more replaceable. As a result, companies are shifting their focus towards retaining specific skill sets rather than individual workers,” says Subburathinam P, chief strategy officer at recruitment services company TeamLease.

“India’s vast population is a double-edged sword—on one hand, it gives the country a competitive advantage in the South Asian market due to abundant labour; on the other, it drives down labour costs,” he adds.

Manikandan says, “Indian manufacturing is losing out to countries like Mexico and Vietnam due to higher costs. What is painful is that this extra cost is not incurred at the factory gate but is because of the higher logistics cost involved. As a result, while the sector has been able to provide good employment to lakhs of people, it has not been able to pass on higher compensation to its workers.”

Finding a Magic Bullet

Realising the difficulties workers face, the Centre is trying to formalise jobs and extend social security benefits to workers. “The efforts are expected to significantly boost the formal sector’s share in India’s employment landscape, thereby providing greater job security, access to social benefits and improved working conditions for a larger portion of the workforce,” says Union labour secretary Sumita Dawra.

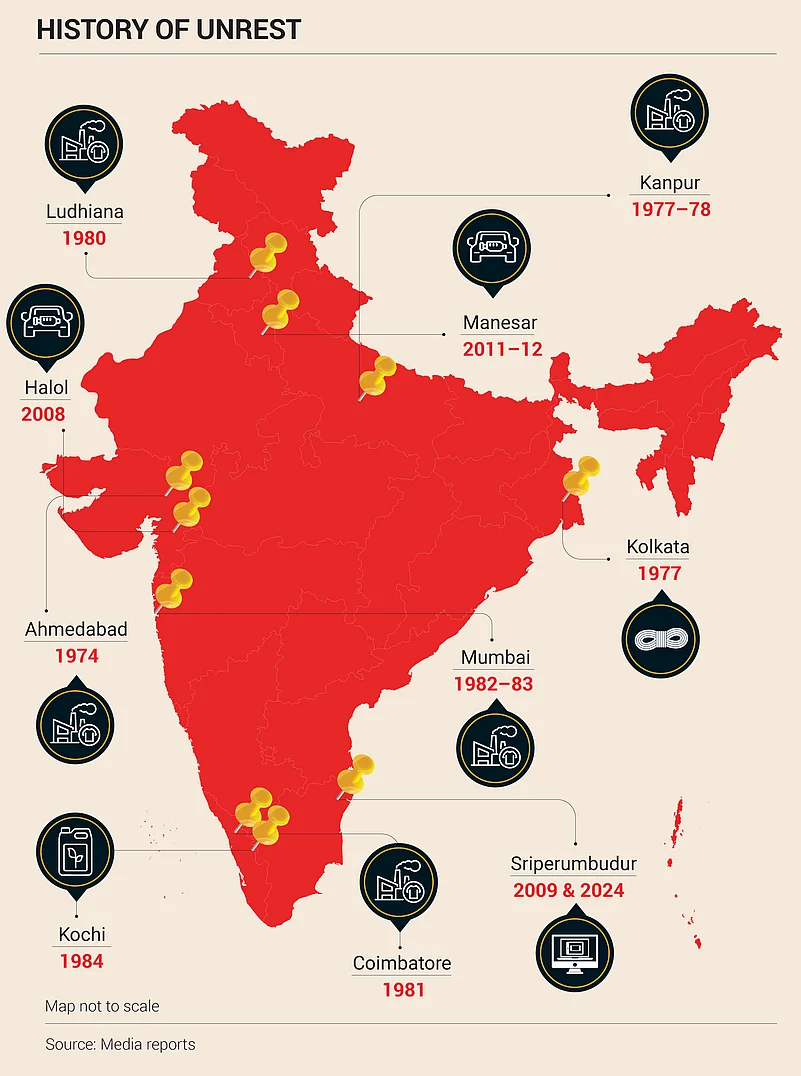

But if formalised workers enjoying relatively better compensation at Samsung can break out in protest, mere formalisation is unlikely to solve the issues facing Indian workers. Labour unrest is not new in India. Several sectors such as textile and automobiles have suffered when workers have grown restive. The 1970s saw militant trade unionism leading to shutting down of a large number of mills and factories.

The unrest at the Samsung plant in Sriperumbudur has sent alarm bells ringing across India’s manufacturing corridors. Labour unrest at a major multinational threatens to undo all the structural gains of the past decade. An inability to find common ground can shatter India’s manufacturing dreams.