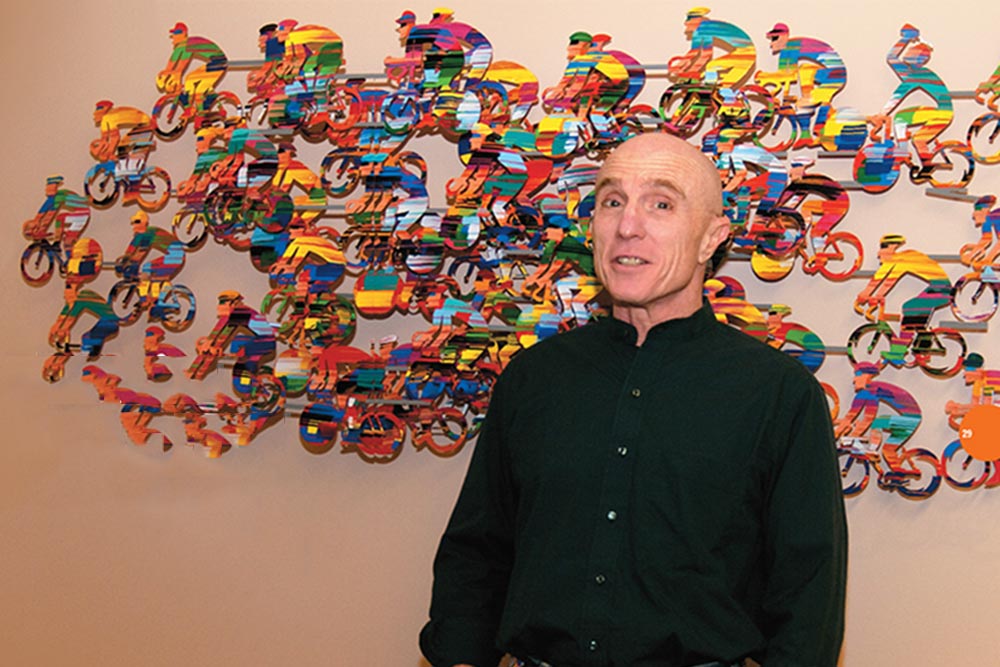

While you do find many venture capital firms cheek by jowl on Sand Hill Road, none has the heritage that Kleiner Perkins Caulfield & Byers does. Its Menlo Park office is a start-up shrine and the buzz at the front office is palpable. That is KPCB keeping up with the times is visible as we pass the parking lot after we are granted access to meet Randy Komisar, a Silicon Valley veteran. If the Energizer folks didn’t have their signature bunny, Komisar would have been a natural choice. It is a bright sunny day and Komisar prefers to get the photo shoot out of the way first. His joie de vivre is evident as he bounces around to the directions of our photographer and then voluntarily displays his own posing style. Once we get down to business, the hyper-energetic Komisar articulates ideas like a woodpecker diligently pecking wood. And yes, what left us wide-eyed in the parking lot was a brutishly muscular Fisker Karma. But lets just say that the $100,000 base price electric hybrid was there because KPCB is an early investor in Fisker Automotive and not due to any thriving partner in particular.

What was your most important learnings as an entrepreneur and a venture capitalist? As is often said, did failures teach you more than success?

It is interesting that in the last couple of years the concept of failure has gotten much more attention in the American economy as people try to digest the claps of the economy post 2008 and try to understand how we think about the future. I have been talking about failure much longer than that. I believe failure is a crucial part of innovation — if you can’t fail, you can’t innovate. So, we need to have an economic outlook that incorporates failure, not just success. There is a movie out recently called The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. There is a wonderful saying in it by the Indian proprietor of the hotel, which is a disaster, but he has grand plans to improve it. As guests come in, very disappointed, he goes, “In the end everything must be good. If it is not good yet, it is not the end.” I think failure is only a problem if you stop at it. If you use failure to get to success, learn and want to improve yourself and improve your next effort, it is just one step on the pathway to success. That is how we have seen failure in Silicon Valley for 70 years. Silicon Valley isn’t successful because of its successes but how it deals with failures. By allowing people to fail by experimenting and innovating, it embraces this idea of learning without penalising the individual.

But this penalisation of the individual is what most companies do. Certainly in Western Europe and many parts of Asia today, if you fail, particularly in large companies, then your opportunities are limited. In Silicon Valley, if you fail for some reason other than the fact that you were corrupt, lazy or stupid, then we want to take advantage of the person’s experience and put it to work in the next success.

Would you agree that failures in start-ups are different from large corporations where failures can have devastating repercussion not only for the organisation but for the economy as well? There is also a moral hazard in accepting failures from large corporations.

I think you cannot innovate in areas where you can’t afford to fail. As the experience of 2008 shows, in the banking space we innovated with products that were not understood, with devastating impact. Those were experiments where we couldn’t afford to fail because they were too big to fail. In which case, you need to narrow your scope in order to effectively innovate. In large corporations, the culture limits your ability to fail. That is why large companies are not great at breakthrough innovation. It is not built into their DNA to take that big a risk.

But are there exceptions, such as 3M, GE, and to some extent, DuPont ?

I do think that incremental innovation is the necessity of any business. If your products aren’t constantly evolving, then your business is not going to be competitive. There is always somebody hot on your heels. However, even in those settings we only see innovations that tend to be much less risky and much less breakthrough in nature. More and more of what is R&D in large corporations happens in small companies now. The budgets in R&D continue to shrink in large corporations every day as they have to deal with quarter-to-quarter results. What they end up doing is having very good M&A teams to find small companies with big ideas and buy them at the right time and create new prongs to their businesses.

Usually, for a large corporation, there are three different phases in innovation. The first phase is easy and most corporations do it and that is small budgets, small teams with new ideas. It is pretty easy for small corporations to handle those sort of innovations. The last stage, stage three, is what I call the cash cow business. It is a business that has scaled, where innovation is just incremental for dealing with competitive responses to the market.

The hard part is the second phase because you may have this little team with five people and they have this new idea or technology like post-it notes, and it works, but you can’t give the resources it requires. You may look at it and think, it may be $12 million business the next year, maybe $20 million the year after and $50 million the year after. The CEO and CFO are looking at a $1 billion-plus business and saying, “It doesn’t matter. Why would I take resources from my billion-dollar enterprise and put it into this $12 million enterprise?” The problem is, that $12 million enterprise has the opportunity to be a $1 billion enterprise in 10 years. There is underinvestment in phase two. It is the hardest phase. It is the phase where people with the good ideas have to fight the people with good business for resources. In a corporate environment, they usually lose that fight, especially if the company is growing. You will say, I will just put 30 more people in Asia and I will sell $200 million more in projects that I already have. That is unfortunate and shortsighted but it is the way quarter-to-quarter business has to be.

Can you give examples to explain of constructive failure?

I will give you an example of a little company called Pinger that we built in the communications area. Right now, they have a really great app for free SMS and free voice calling. But interestingly enough, when we incubated them in 2005, they had a completely different idea. Their idea was to create an asynchronous voice messaging service. The thesis was that people would prefer voice over text so we need to create a platform where voice is as fluid and as easy to navigate as text. They came out of Palm and had a lot of experience in the smartphone area at the time. So they built this great product. And nobody wanted it. We could have just closed the doors at that point and that would have been the end. But because they were using the dashboard process, rather than slavishly executing to a business plan, they were quick to identify the problem in the business and understand how to grab the greater opportunity. So they figured out that people were, in fact, very interested in voice but with SMS.

The iPhone hadn’t come out yet, so they created one app that would allow you SMS, chat and voice messaging. They saw better results than the first time but not great. They measured even more carefully, and what they saw was that people really like this app but what they were using was really SMS. Now, that was a 180-degree shift from their original thesis. So they went out and built another app — free SMS — and it came out with the iPhone. The company took off. Now, Pinger is the fifth-largest originator of messaging on mobile networks of everybody. They are just behind Skype. And they have now added free voice to it as well. But they got there by failing twice. They did not end the game with those failures but used the negative experience to improve their product and build a very successful business.

Any more examples?

PayPal. When PayPal started it was a business that was simply looking to put together a risk and security algorithm that allowed you to detect fraud. But they couldn’t make the business work. So they kept iterating and it was only on Plan H that they were able to find a business in the mobile payments space. They discovered that by failing at each one of their incremental ideas and learning about the customer and the market.

Google is an extremely interesting example, too. When Google came out it was going to be a white label search engine — they were going to be providing search for AOL, Yahoo! and Netscape. That wasn’t a very good business. But they saw this little company called Goto, which was in the search space and selling a position on each one of the search results. Users didn’t like that because they didn’t get the search results they wanted, because results depended on how much somebody was paying, not how relevant the results were. The Google guys said, “If we separate the ads from the search results and put it on the right hand side and charge for it, it would be a good model.” And there is Google.

Intel is another very interesting example. Intel started off in the DRAM business. They were pretty successful for a while, but then the Japanese came in and swamped the market with ridiculously low costs. There was a story — I don’t know if it is true but I love the story. One day Andy Grove had all his people come into his office and said, “Listen, the Japanese are eating our lunch. We are getting killed in this market. The board is going to come in next month and they are going to replace all of us. What will the new guys do?” Someone said something, someone else said something else and one guy said, “I am working on this small microprocessor. It doesn’t do much but it is working in calculators, and there are a few interested customers for this.” Andy looked up and said, “From now we are in the microprocessor business.” He said, “We are the new guys. We can be replaced and the new guys can come in or we could be the new guys.”

I love that story. Because it shows that you have to take your failure and think about what the new guys can do if you guys were exited from the building. That is how to make failure successful — to be the new guys in the face of failure.

What was the genesis of your book Getting to Plan B?

I came about the concept of Plan B when I was at Stanford. I was looking at my students who were all trying to go off to build businesses and John Mullings, who was visiting Stanford then, came to me and we got thinking about the whole challenge of how the business plan for an early-stage venture evolves into the operating company that is ultimately successful. As it turned out, we found that 90% of successful companies were built on success that was not anticipated. In other words, 90% of the companies failed in their original plan. If that is true, I thought, why would I drive my students through the conventional process of developing a business plan and executing that plan only to fail? We wanted to develop an alternate process, which was Plan B.

Plan B is a way of thinking about innovation that anticipates failure and how to turn failure into success. The conventional way businesses have been practising in Silicon Valley has been that you create a business plan, you walk in to an investor, they agree to fund your plan, then you walk into the first board meeting and you start showing them your progress against that plan. The problem with that is, your plan was built before you had a product or a customer and somewhere in the marketplace you probably had a competitor. If your plan is right, it is a coincidence, not brilliance. It has to be wrong. It is built upon too many assumptions. So if that is true, what is the better process of innovation? How can you discover your business model rather than execute around a set of assumptions?

If you execute against a set of assumptions, you start telling lies to each other. The investor wants to hear that you are on track, the CEO and the entrepreneur wants to say that things are on track. The investor is trying to get information that makes them doubt their assumptions but the entrepreneur does not want to share it because they think that the investors invested in a plan and will be disappointed. That is when the lies start. The issue with that is, a year down the line when the venture fails, you fire the management team, you bring in a new team and you reconstruct the business. Essentially, you bring in the new guys. Getting to Plan B is built around the notion that you are the new guys. Plan B is about not telling lies to each other and instead having a disciplined, methodical process of discovering your business while anticipating that you are wrong along the way.

Often people believe that Plan B means you have to have two plans. That is not what it means. Plan B means you have one plan, you measure well, you react to the market, and you evolve to the next plan, but you evolve empirically. It’s not a hedge plan. You have a plan that can’t fail, but if it does then we develop Plan B.

At what point in an investment do you consider going horizontal, that is, look at new markets or feature?

In early-stage companies, what is the most critical is focus. Developing a killer value proposition with your solution is essential for your success. So thinking horizontal at an early stage, to me, has a negative connotation. Because that becomes hedging and hedging isn’t good. In large companies you can hedge because you can’t accept failure, but in a small, entrepreneurial company you have to take a single bet because that is all you can afford to execute. You have got to do it fast, efficiently, cheaply and with precision.

When entrepreneurs start coming to me with horizontal strategies around a value propostion — we could do it in this market or in that market and so on — usually, that tells me is their ambition is not working. It is a signal to me not to hedge but to reassess and pull back.

The time to move horizontal is in the third phase of innovation, when you have scaled your existing business and you are looking for incremental business around that. You don’t have to invent your core product or your business model, just see where you can get synergies and potentially leverage your existing infrastructure. That is usually when your innovation becomes a cash cow.

What kind of ventures do you like?

Principally, I look for a big problem to solve. Then, I look for people who can execute well and, more importantly, learn along the way, not just people who are smart. The third thing I need is a value proposition, not a business model because when somebody comes and tells me a business model, it is wrong anyway because they have not put the product out yet. And if I wait for the business model, it’s going to be too late. So what I need is an excellent value proposition; after that, I can figure out how to capture that value.

There are many people in Silicon valley who have a thesis about the future and I call that looking for your keys under the light. I don’t like to do that, I like to listen to the keys tinkling in the bushes. I like to look for that big idea out there.

Let me give you an example. Transphorm was a wonderful company started by two Indian entrepreneurs down in Santa Barbara. They had this new material, gallium nitride, that could transform the power supply business and we incubated the idea. Seven years later, they came up with this breakthrough product that could save up to 50% or more of the wasted energy in power switching. Power switching wastes most of the energy off the grid, going from AC to DC and DC to AC. These guys have it. It is fantastic. I knew nothing about Umesh Mishra, the co-founder of Transphorm, who came up with this idea. Nor did I know anything about power supplies. But Mishra came across as a fantastic guy and I believed in the problem he was solving. It took a long time, but we are now shipping the product.

Another business is Nest Labs, founded by Tony Fadell of Apple, who invented the iPod, and Matt Rogers. Tony was building a house that would be energy efficient but he was running into problems. One day, Tony and Matt came into my office and said they wanted to build a smart thermostat. We thought it could be an interesting business but may not be too big. The slogan of Nest is that it is a smart thermostat but it is much more — it has three sensors in it and two radios. It allows you to connect with any devices that will have sensors around the home, around something called the Nest Sense Network. So they are building an interoperable smart sensing environment for products in the home starting from a simple thermostat. This may be one of the fastest growing businesses that we have seen here over a decade. If you look at it, thermostat business is not something people were dying to invest in, but when you see it as venture where someone like Tony and Matt are trying to make our environment smarter, then the whole thing changes. That company is a darling. The market loves them. The new products they will put out next year are just brilliant. So the combination I look for is scale, right people and a great value proposition.

What are the most promising emerging trends?

Clearly, this move to global and mobile is very interesting. What happens in a world where everything is going mobile? What happens in a world full of sensors? What is very interesting to me is the internet of things. We have seen the internet of communications, internet of content, internet of media and the internet of people. What’s next? I think it’s going to be the internet of things — things will start to talk to each other. It is like having robotics in a distributed way where every device becomes smart and as a result you don’t have to make so many choices, you don’t have to think as much, you don’t have to think as hard.

Who is doing cutting edge work in this area?

Nest is one. There is another company called Enlighted, which makes these intelligent light devices that will know: is the sun coming in brightly enough through the window or not; is there someone in the room or not; can I dim this by 30% and is anybody complaining; if they are, put it back up, and so on. You start to make your environment smart so that you don’t have to make so many decisions every day. And then, there is this company called Find the Best. I love this company. This guy came to me and said, “There is all this data out there and people can’t make any sense of it. How can they make decisions or choices?” So he created a series of apps called comps where you can compare things — smartphones or schools or what you may. That company is doing incredibly well. They have got 12 million a month in uniques and they are not spending a penny on marketing. Today, anybody close to making decisions that are transactional is in the second-best position to Google to monetise. Google has been the only business that has been close to a decision and that is how they do so well. When you are searching, that is a really good time to get your information. When you are comparing, that is an even better time.