The abolition of Planning Commission in 2014 by the Union government brought a paradigm shift in the Indian economic policy discourse. With the government following a changed approach in planning policies, the Indian Foreign Trade Policy (FTP) 2023 was announced on March 31, 2023, after a three-year delay. The policy came at a time when the fragility of Indian trade was laid bare by the Covid-19 pandemic.

When the policy was introduced, it was expected to acknowledge and address the critical issues concerning the state of Indian trade which have been ailing the sector for years. Only by answering these concerns can an effective framework be formulated for ensuring a high-value-added and employment generating future for Indian trade.

However, the policy was plagued by abandonment of planned targets, absence of specified timelines and inadequate budgetary provision. Further, the lack of timely publication of nationally representative survey data made it difficult to conduct independent assessment and public scrutiny.

Critical Questions Over Trade

To understand the problems of Indian trade, one needs to look at the state and trend of the non-oil merchandise sector in last two decades. As petrochemicals products are highly capital-intensive commodities, this sector does not hold much dependable promise for export-led employment generation.

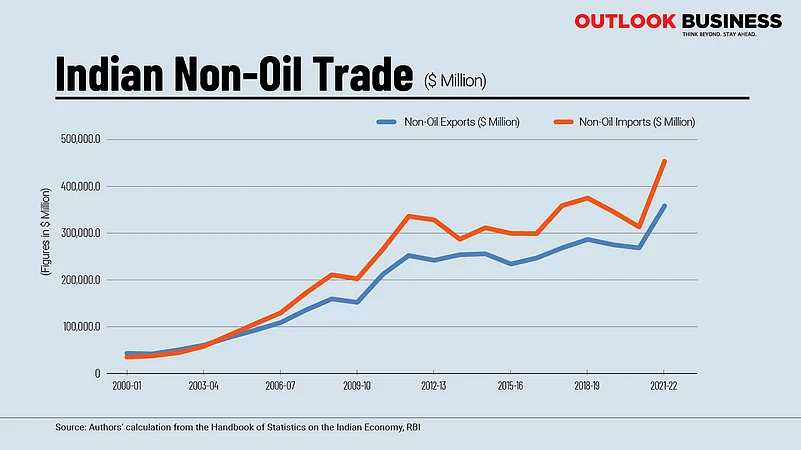

The export-import data for the non-oil merchandise sector from 2000-01 showcases how exports have not been able to keep up with the pace of rising imports of such commodities.

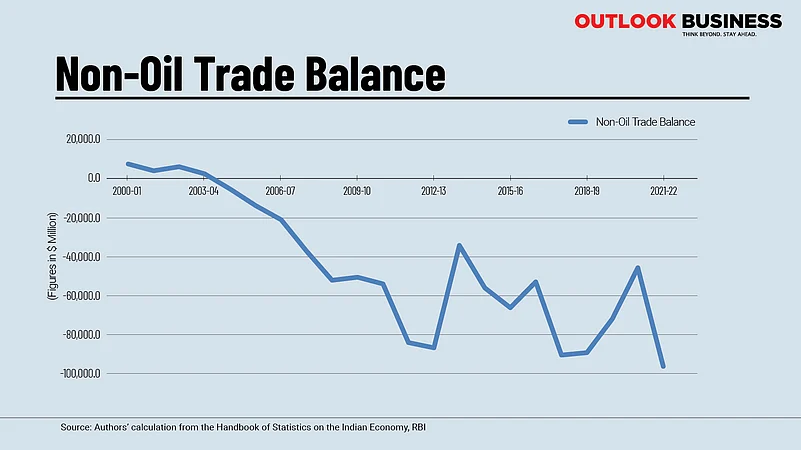

Starting with a positive trade surplus in the non-oil merchandise sector in early 2000s, India’s non-oil trade deficit had ballooned to around $100 billion in 2021-22.

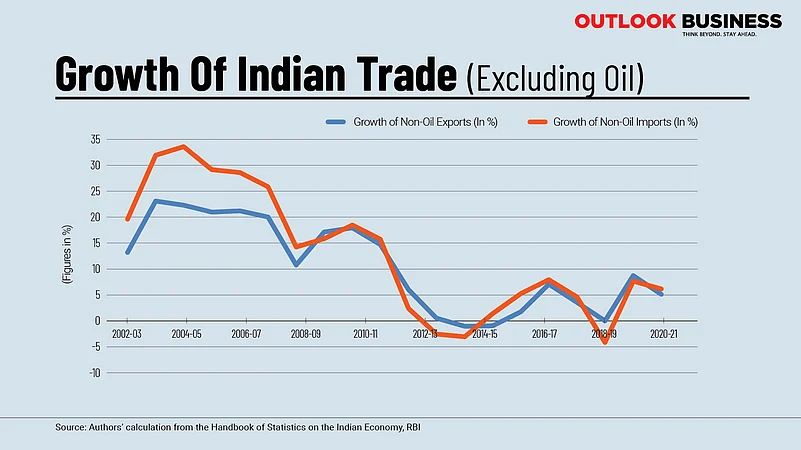

The effect of rising imports in this category could have been offset, had there been higher levels of exports and successive growth. The fact is that the growth of the Indian exports had drastically dropped from annual 3 years moving average of 18 per cent in the period 2000-2011 to 2.4 per cent in 2012-2018—well before the Covid-19 pandemic. In contrast, both levels and growth of the Indian imports have been higher, about 23 per cent in the period 2000-2011, and fallen thereafter along with India’s exports.

The poor performance of exports cannot be overlooked as a temporary phenomenon. One needs to look at the foundational economic limitations which warrant much needed policy attention.

For any policy to be able to successfully address these limitations, it needs to acknowledge the fact that India’s exports have been subdued in the last decade. While India has been import-dependent for meeting its crude oil requirements, the data shows an overdependence on imports for commodities which could be developed and produced domestically. Due to this, India has been stuck in a permanent tide of trade deficit since 2004 in non-oil trade category.

Not only has India not been able to cut reliance on imports for non-oil commodities, but the country is also not in the position to capitalise the high-tech manufacturing companies those are looking for diversifying their production base from China with rising geopolitical tensions.

To devise an effective trade policy, these issues needed to be answered by policymakers. However, FTP 2023 has failed to bring about fundamental changes in policy discourse by ignoring the problems.

Concerns Remain

Given the increasing fragility in the Indian external sector and emerging challenges in the domestic economy, the FTP 2023 has not been able to devise an effective and time-bound policy trajectory for high-value-added and employment generating future of the Indian trade. The limitation of high-skilled labour, investment in R&D, priority-based credit lending, advanced training and entrepreneurship have received little attention, if at all.

India’s trade policy formulation has failed to align itself with its socio-economic reality and developmental priorities. It instead has followed a blindfolded WTO-obligatory framework. FTP 2023 is grossly a continuity of the status quo of broad WTO directions in the line of second phase of trade reform with further deregulation, promoting ‘ease of doing business’, facilitating paperless trade and promoting e-commerce. Although important, these are at best the logistical side of the trade, not essentially the foundational limitations that the Indian exports face.

The sluggish pace of exports growth is the obvious consequence of neglecting public investment in education and skills, low investment in R&D, and most importantly, conspicuous absence of foresights about the fast-changing direction of global trade in diversified, high value-added, and emerging products, i.e., the ‘green technology’ sector. The essential role of public finance, achieving all these, could well be learnt from the Chinese experience of meteoritic rise in world trade.

Perhaps now, it becomes difficult for Indian economic policy circles to ignore Amartya Sen’s decades long advocacy for ‘capability approach’—essentialising government intervention on quality health services and education—in building ‘healthy and educated’ workforce. The exposed fragility of exports is nothing but one of the obvious structural outcomes of Sen’s concerns.

While there has been an attempt in the direction of export diversification and decentralisation by building district-specific export hubs, the policy doesn’t clarify the budgetary provision and the timeline for bringing the districts as exports hubs. FTP 2023 is not only a delayed intervention by three years beyond the tenure of the FTP 2015-2020, but it is also a striking departure from conventionally followed five-yearly trade planning—following the erstwhile Planning Commission’s plans—by not specifying any well-defined timeline.

Moreover, the skilling and mentorship initiatives for new entrepreneurs and potential exporters have grossly been obligated to ‘status holder’ export firms, shifting the governmental responsibility away from building much needed educated and skilled labour force at the macro level.

As FTP 2023 fails to address the multiple challenges faced by Indian trade sector today, it can invisibly divert the public attention as well. Subsequently, this can further dilute the government’s responsibility to achieve any well-specified trade objectives and democratic accountability.