When Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented her final full-budget speech for the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government’s second five-year term, she was in a situation similar to the one faced by Congress leader P. Chidambaram when he was the finance minister of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in 2013. On both the occasions, the Indian economy was facing global headwinds, flight of foreign capital due to rising interest rates and an opposition levying charges of corruption and favouring certain industrialists.

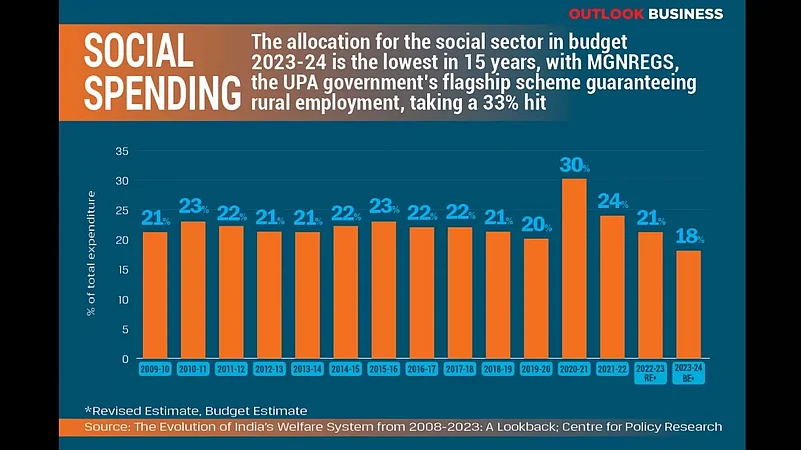

A difficult economic situation—especially in the final year of a term—forces governments to extend dole-outs to the public in order to downplay the looming dangers. But Sitharaman chose not to go down the oft-trodden path. Instead, she stuck to her government’s anti-freebies stance. Not just this, she also slashed the allocation for a few ongoing social sector schemes while harping on infrastructure development.

Advertisement

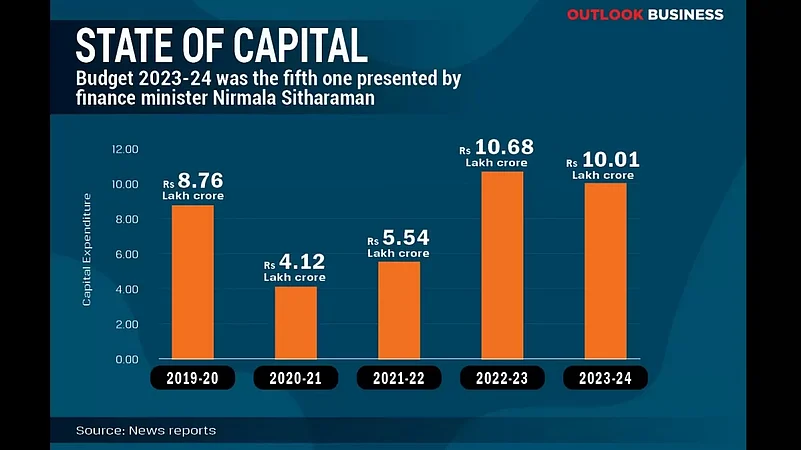

Continuing with the theme of creating infrastructure, Sitharaman proposed a capital expenditure of Rs 10 lakh crore for 2023–24, a three-fold jump over the allocation announced in her first budget speech for 2019–20. Spending on infrastructure has been the hallmark of the Narendra Modi government ever since it came to power in 2014, but this time it came in the absence of much growth in revenue.

Social Sector Squeeze

Unlike the UPA government which used social sector expenditure to woo the voters in 2013, Sitharaman’s axe fell directly on the sector. The UPA government’s flagship Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), which promises 100 days of work to the rural population, received a 33 per cent cut in budget allocation compared to the revised estimate of Rs 89,400 crore for the scheme in the current financial year.

Advertisement

Modi, a critic of the rural employment scheme, had criticised it as the epitome of the UPA government’s failure soon after coming to power in 2014. Last year, the government had constituted a high-powered panel under the chairmanship of former agriculture secretary Amarjeet Sinha to study the impact of MGNREGS in poverty alleviation since its inception. Even though the scheme proved to be a lifesaver for millions of poor people during the Covid-19 years, it has very few backers within the government.

Interestingly, 14 states have claimed arrears from the Centre for payment of wages under the scheme for the current financial year. The latest reports suggest that the Centre owes Rs 2,700 crore to West Bengal. It has invoked Section 27 of the MGNREGA 2005 which allows the Union government to halt release of funds to a state on complaints of irregularities in fund utilisation. Out of the 14 states, eight are ruled by the opposition.

The government, however, has maintained that MGNREGS is a demand-based scheme and the revised estimates can always go up depending upon the job demand coming from villages.

Another scheme that bore the brunt of higher capital expenditure was the Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman (previously the mid-day meal scheme). Its allocation has been slashed by over 9 per cent to Rs 11,600 crore, as against the revised estimates of Rs 12,800 crore for the ongoing financial year.

The PM Poshan scheme is also facing delay in release of funds from the Centre. With just one month remaining in the current financial year, the Centre has released just half of the total outlay for the scheme for the year.

Advertisement

The Infra Dividend

All governments want to build infrastructure, but the NDA government's obsession with it is unprecedented. The effective capital expenditure for FY24 will account for 4.5 per cent of India’s gross domestic product. This involves building highways, railway lines, ports and airports among others.

The NDA has effectively followed the philosophy of “roads for development” to push India’s growth. “Today, highways are being built in India at a speed of 38 kilometres per day and more than five kilometres of rail lines are being laid every day. Our port capacity is going to reach 3,000 MTPA in the coming two years. Compared to 2014, the number of operational airports has doubled from 74 to 147. In these nine years, about 3.5 lakh kilometres of rural roads and 80,000 kilometres of national highways have been built. In these nine years, houses of 3 crore poor have been built,” said Modi at a recent event.

Advertisement

Dignitaries of the UPA government have taken offence at the Centre’s claims of constructing more highways per day than its predecessor. But there is even bigger data that goes against this rush for infrastructure spend.

India sold just 17.51 million vehicles in 2021–22, as against 21.86 million vehicles in 2016–17, according to the data available with Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers. The decline of over 19 per cent in total vehicle sales in the post-Covid economy hints at the destroyed consumption capacity of Indians. It may be argued that the construction sector creates jobs at the lower end of the pyramid, which fuels spending among the masses, but it has not been reflected in the Indian economy as commensurate with the amount of money spent on creating infrastructure by the government.

Advertisement

The private final consumption expenditure (PFCE)—a measure of households and the private sector’s expenditure in the economy—has grown at a compounded rate of 10.74 per cent between 2014–15 and 2021–22 (the NDA government’s tenure). If we compare it with the period of the UPA government’s rule, the PFCE registered a growth of 13.29 per cent between 2004–05 and 2013–14. Government supporters would argue that the 3 percentage point difference in the annual growth rate is due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but the UPA government too had to deal with the global financial crisis in its tenure.

Infra Versus Social

Former finance secretary Subhash Garg is critical of the nature of the government’s expenditure under the infrastructure domain.

Advertisement

“The finance minister presented her budget in a manner to make it look progressive and focused on long-term asset creation. But in reality, a large part of the big capital expenditure substitutes the capex financed by public sector undertakings and states by their own resources,” says Garg, referring to the inability of the railways and the National Highways Authority of India to borrow from the market. “A good part is for financially unviable projects and thereby, in effect, [is] revenue expenditure and not really capital expenditure,” he adds, wondering whether these expenditures will generate any revenue.

Garg criticises the government for not being serious enough about bringing down the high fiscal deficit. The estimated FY24 fiscal deficit is 5.9 per cent, which is way above the fiscal responsibility and budget management [FRBM] target of 3 per cent. “The government used Covid-19 to abandon fiscal rectitude and embarked on expanding expenditures hugely for populist programmes like free foodgrains, free fertilisers and PM KISAN and also to complete long-pending but largely non-commercial railways, roads and telecom projects. For four years running until 2024, the government will be running fiscal deficit in excess of 6 per cent of GDP,” he notes, observing that it needs to think about the sustainability of high expenditure and risks of high fiscal deficits on the Indian economy and the people.

It is not that there is no spending in the social sector. What has happened is that the nature of this spending has changed under the NDA government, says Avani Kapur, a senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research. While the government has increased expenditure on schemes that are infrastructure-based or are direct entitlements to citizens, the programmes that do not show immediate outcome have received less priority, she observes.

“Education schemes such as Samagra Shiksha, PM Poshan and supplementary nutrition programmes have received a cut in their allocations in real-terms whereas, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojna (PMAY-G), Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM-G), and the Jal Jeevan Mission have received higher allocation over the years,” she adds.

Spend, Not Save

Much like the punctuation, the pattern of money use by the public is expected to shift places, thanks to Sitharaman’s push for a consumption-led society by making the new tax regime a default option for the taxpayers.

The new regime does not give rebates for investments and home loan interest payments to individuals. It relies on a flat deduction to taxpayers with income up to Rs 7 lakh per annum. The idea finds backing in the government’s philosophy of making taxation simpler to improve collections. However, it comes at a cost for the taxpayers who rely on exemptions to save money from their meagre earnings each year.

Given the high tax slabs in India, an average individual in the highest slab will pay 39 per cent of income in taxes from the next financial year—the rate is 42 per cent in the current financial year. The effective tax rate for corporations on the other hand is 25.17 per cent (inclusive of 10 per cent surcharge and 4 per cent cess) from 2019. This is one reason why corporation tax became popular with immediate effect but there have been few takers for the new tax regime among individual taxpayers.

Chidambaram is of the view that while the government wants to move towards an exemption-less tax regime for individuals like it did for corporates, the effective rate of tax on individuals is too much.

“The new tax regime disincentivises saving. The natural human behaviour is to spend … So, the government’s job is to promote savings among people. But the government is sending the message that do not save, spend …,” says Chidambaram. Household savings will collapse if everybody takes the message of the government to heart and spends rather than save, he warns. "In that case, where will the government get capital formation for investment in the country?” he wonders.

Chidambaram’s concern echoes in a recent report by brokerage firm Motilal Oswal that estimates the net financial savings of Indian households to have declined to a three-decade low of 4 per cent of the GDP in the first half of the ongoing fiscal year.

Nikhil Gupta, chief economist at Motilal Oswal, believes that the declining savings rate will impact the growth of Indian GDP over the next few years as there is limited room for income growth in the coming years for the individuals.

“Household financial savings were at their peak of 10 per cent to 11 per cent from FY08 to FY12. Even in FY12, [the figure] was close to 10 per cent or so. Somewhere in that year, it fell to 7.5 per cent. Since then, it has been close to 7.5 per cent,” Gupta notes, adding that FY21 was an exception when the savings surged because of Covid-19.

When the savings are low, investments can increase only with external borrowing and higher importing, which will lead to a higher current account deficit (CAD), he explains. “This means that there will be higher GDP growth only with a higher CAD. I do not think the RBI or the government is okay with a high CAD in India,” Gupta says.

While India continues to be a bright spot among global economies with official projections of above 6 per cent GDP growth rate in the coming years, Sitharaman’s is a clear bet on physical over social infrastructure. There is some time before a clear winner between the current government and its predecessor emerges.

Just one email a week

Just one email a week