The falling value of the India rupee has become a cause of concern for the economy. While experts are divided on the immediate impact of fast depreciating rupee on the Indian economy, there’s a broad consensus on the fact that India must have a strategy to control its forex outgo as a result of increasing import bill. Interestingly, encouraging the indigenous production of edible oil can help cut down import bill, as edible oil import constitutes about 2.8 per cent of the total imports during the past 10 years for India.

In such a move, the GEAC (Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee) recently gave environmental clearance to mustard hybrid DMH-11 for ‘larger field trials’. If the government does not budge in front of naysayers of the GM (genetically modified) crop this time, as they did in 2009 after giving in-principle nod to transgenic Bt Brinjal and rolling it back, DMH-11 would become the first GM ‘food’ crop. It will only be the second crop, after Bt cotton, to be commercially produced after necessary field trials.

This could be a significant development not just for mustard farmers in India, who are battling against near-stagnant yield, but may also aid India in dropping its non-coveted tag of being the largest importer of edible oil.

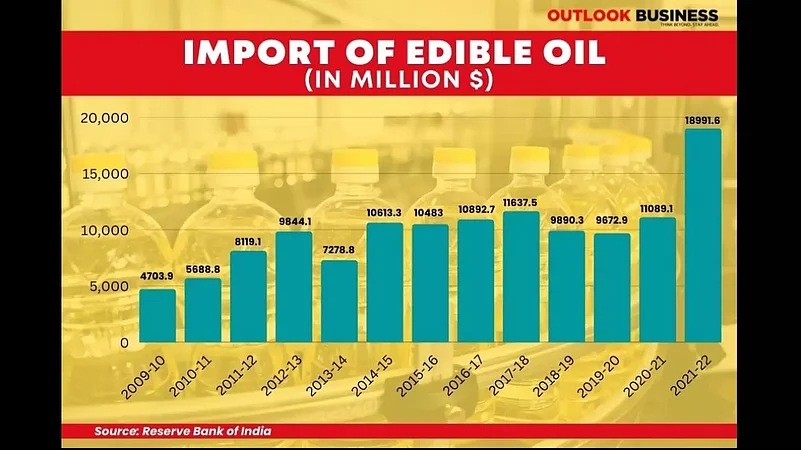

Rising Import Bill Of Edible Oil

The import bill of edible vegetable oil rose by 21 per cent in 2020-21 over 2019-20, which further galloped by 63 per cent in FY22 over FY21. This is despite a decline in the import volume, as the prices of edible oil rose in the international market, in addition to the depreciation in the value of the Indian rupee.

Keeping this is mind, the National Mission on Edible Oils - Oil Palm (NMEO-OP) was launched in 2021 to make India self-sufficient in cooking oils, including palm oil. India’s dependency on edible import is alarmingly higher, compared to other major countries. While most of the countries are dependent on imported edible oil in the range of 30-39 per cent, India’s dependency ranges from 55-60 per cent.

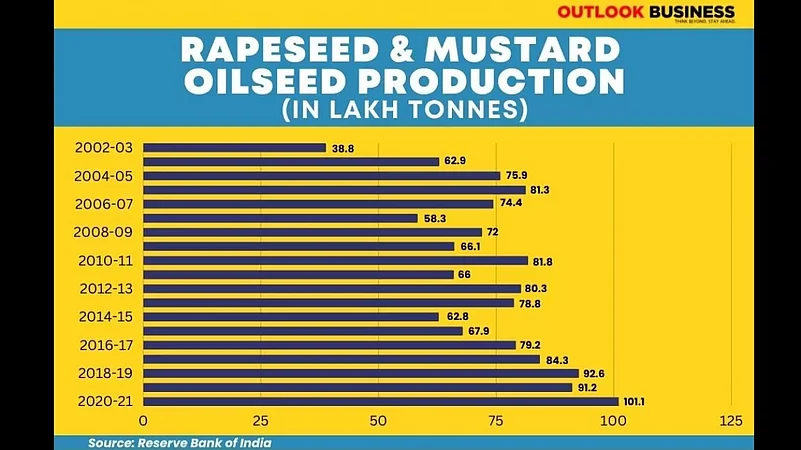

Stagnant Output Of Oilseeds

Almost 72 per cent of the total area, where oilseeds are cultivated in India, is confined to rainfed areas. These are cultivated mostly by marginal and small farmers, reducing the possibility of farm mechanisation, and thus adversely affecting its yield.

To increase production, several programmes like NFSM (National Food Security Mission) oilseeds, TRFA (Targeting Rice Fallow Area ) oilseeds, seed hubs on oilseeds, and cluster demonstrations of improved technology have been launched. In addition, the union government has not only announced regular minimum support price (MSP) increases, but has also ensured multi-fold increase in procurement of crops at MSP. In 2019-20 and 2020-21, India recorded its highest oilseeds production. However, this is only at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 1.94 per cent — from 298 lakh tonnes in FY12 to 361 lakh tonnes in FY21. This does not match pace with the increasing demand for edible oil in the country. The per capita consumption of edible oil in India is growing at a CAGR of around 5% from 16.20 kg per annum in FY14 to 19.5 kg per annum in FY18.

Does Technology Hold The Key?

Overall, nine oilseed crops are grown in India. Among them, the highest average contribution to total production of oilseeds is of soybean at 38 per cent, followed by rapeseed-mustard at 27 per cent and groundnut at 27 per cent (average of 2016-17 to 2020-21).

The GM mustard crop technology was developed by Deepak Pental, a geneticist and former vice-chancellor of Delhi University, and his team after a decade-long effort. The technology claims to increase the yield of the crop by 30-35 per cent. The results from other countries seem to corroborate this. Bangladesh, which introduced Bt brinjal in 2013, has seen its production and yield increase. The Bt gene produces a protein that is toxic to the borer pest but harmless to other types of insects and humans. The crop has managed to reduce pesticide use by as much as 84 times a season. Now, Bt brinjal farmers are found to be earning six-times as much as their non-Bt counterparts every year in Bangladesh.

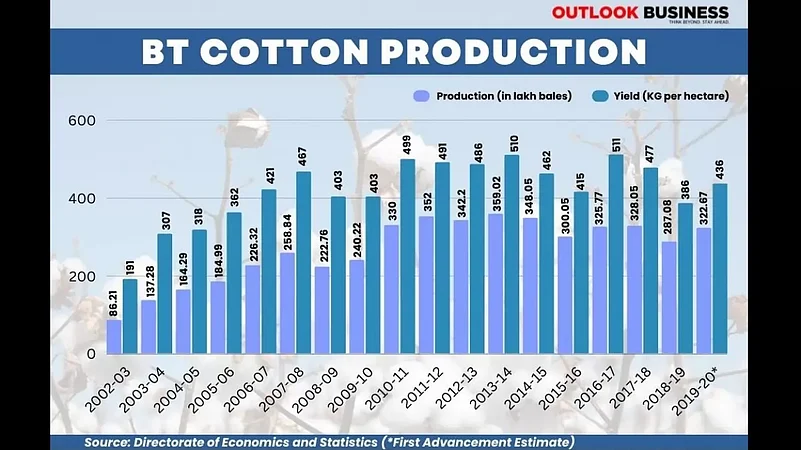

Back here in India, the commercial production of Bt cotton since 2002 has not only increased the total yield per hectare, but has made India the top producer of cotton in the world. The Bt cotton success story holds several lessons for policymakers.

India is a vast country with its own challenges and opportunities. Keeping in mind the global turmoil and food security challenges, expected to get exacerbated by the climate change threat, reliance on technology seems to be a viable option. At least, the trials should not be stopped to know about the efficacy of claims and counter-claims. It looks like the government has made up its mind this time, putting an end to its dilly-dallying attitude about GM crops.