He does it for the family. Ask an average middle-aged Indian man or woman why they work 48-hour weeks (Indians are the seventh-most hardworking people on the planet), and they will tell you that they do it for the family. Seventy-five years of democracy and universal suffragette later, families continue to be the fundamental unit of society, especially among older Indians, the ones most keen on transferring their wealth to millennials and Gen Z.

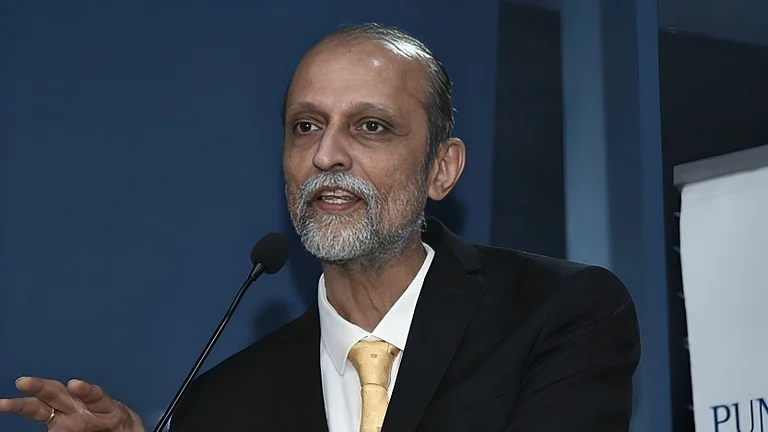

Thus, when Sam Pitroda, the United States-based advisor of the Congress party, said inheritance tax could be a way to address wealth inequality, Indians, especially the wealthier lot, took note. Pitroda said, “In America, there is an inheritance tax. If one has $100 million worth of wealth, when he dies, he can only transfer probably 45 per cent to his children. Fifty-five per cent goes to the government. That is an interesting law.”

The suggestion, in election season, triggered a tsunami of controversy. Even the prime minister waded into the row. Inheritance is what most Indians work towards—to ensure their children would not have to start from scratch. Transfer of wealth to future generations often forms the raison d’etre of economic function in Indian households.

And this is not the first time India was talking about an inheritance tax. An inheritance tax, by another name, did exist in India in the years following Independence. Called ‘estate duty’, it was imposed by Fabian socialist Jawaharlal Nehru’s government.

The tax levied was progressive with rates in the range of 7.5 per cent for a wealth corpus of Rs 1 lakh to 85 per cent for a corpus of Rs 20 lakh. It applied on all property within the territory of India and was levied on the estate of the deceased. The goal was to redistribute wealth, preventing its concentration in the hands of a few.

The tax was done away with by Nehru’s grandson Rajiv Gandhi when the Government of India realised that it was spending more money collecting the taxes than it was making by collecting it. For instance, according to the regular budget of 1980–81, gross revenue in 1979–80 was Rs 11,447 crore. Of this, estate duty made up for Rs 13 crore, just about 0.1 per cent. The cost of collecting this tax was significantly more.

Yet the repeal was controversial. Some argued this would lead to widening of the wealth gap in India. A recent study by French economist Thomas Piketty and his team for the World Inequality Lab found inequality in India had come down in the years following Independence and started rising from the 1980s and rose at a brisk pace from the 2000s.

The question of whether inheritance tax should be reintroduced has been debated repeatedly in India. The argument has been that if more developed economies, such as the US, can have an inheritance tax, and that does not impede growth or incentive, then what stops India.

Can Inheritance Tax Defeat Inequality?

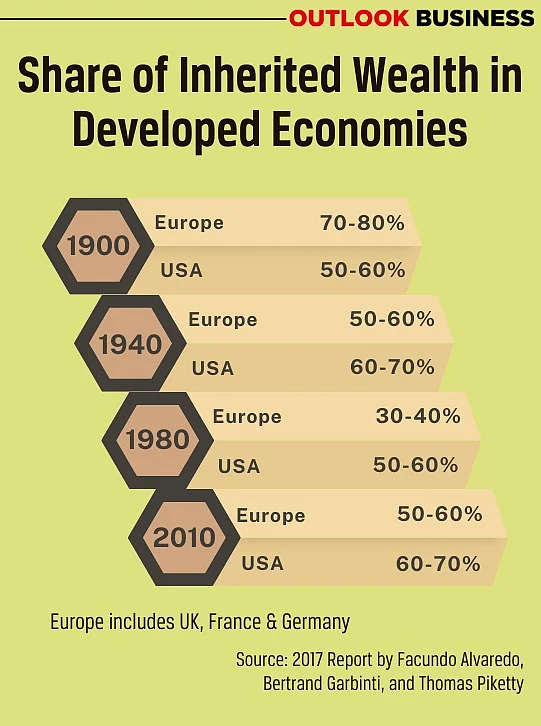

Inheritance tax is not a new idea. Developed economies started adopting versions of inheritance tax in the 1900s, when inherited wealth made up for nearly 80 per cent of all wealth. This led to a gradual decline in the share of inherited wealth, with it going down to below 40 per cent by the 1980s of total wealth. Since then, however, the share of inherited wealth has been increasing. In recent times, that number has been estimated to be between 70 per cent to 80 per cent, nearly the same share as it was in the 1900s.

The American example of inheritance tax, cited by Pitroda, is a limited one. This is because the tax is levied in only six out of 50 American states, and even that is not in a uniform way. Despite having inheritance tax, inequality continues to be a major problem in the US economy. The country is among the most unequal countries among developed economies.

Top one per cent Americans have a combined wealth of $34.2 trillion, or 30.4 per cent of all household wealth in the country. The bottom 50 per cent of the population holds just $2.1 trillion, according to estimates of the Federal reserve. The wealthiest Americans hold more than 88 per cent of all available equity in corporations and mutual fund shares.

“Countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and others levy estate duty or inheritance tax to mitigate economic inequality. However, statistics suggest that it has not helped countries achieve the desired objective of bridging the gap between the rich and the poor,” says Amit Pathak, managing director of Warmond, one of India’s oldest fiduciary services companies.

But there does exist evidence to the contrary.

A 2021 report published by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) found that countries that impose top marginal inheritance tax rates above 30 per cent tend to have a lower Gini index — the statistical measure of income, wealth or consumption inequality.

The report makes the policy suggestion that taxing inheritances and gifts can play an important role in enhancing equality of opportunity and reducing wealth gaps. But Jiger Saiya, partner and leader of tax and regulatory services at MSKA & Associates, a member firm of BDO International, says the correlation made in the story is not direct. “The report does not claim that inheritance tax creates perfect equality. In fact, other factors like access to education, quality of jobs and social safety also significantly impact income inequality,” he adds.

Saurrav Sood, practice leader, international tax and transfer pricing, at SW India says inheritance tax, in countries which have imposed it, has not worked. “This tax has been introduced with the intention to promote equal opportunities by taxing the wealth one inherits as family heritage. But in its present form and due to the old law draft, at present, it seems there are many flaws and loopholes that prohibit it from achieving its desired purpose,” he says.

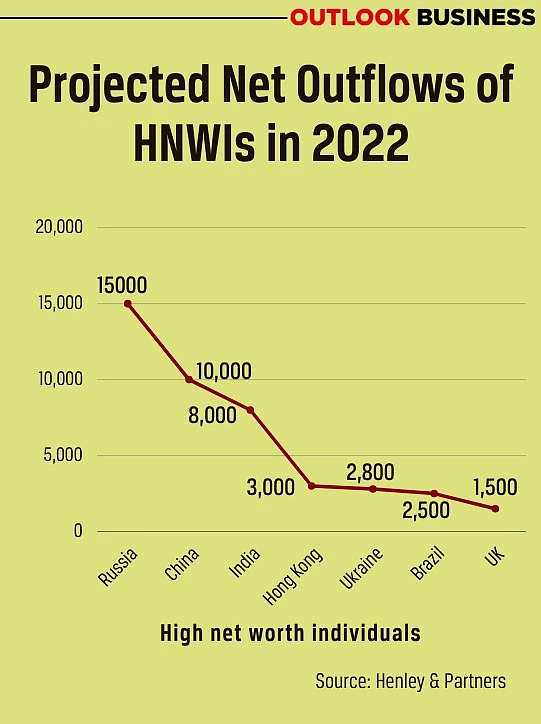

Tax experts are of the view that many people who are supposed to pay inheritance tax in developed economies bypass it, and the same story will play out in India. Ultra-rich Indians already have a penchant for leaving the country. India ranks second in the world in losing high net-worth individuals (HNWIs), right after China.

An estimated 6,500 HNWIs left the country in 2023, according to the Henley Private Wealth Migration Report. A higher number of HNWIs had left the country in 2022 — around 7,500. Can taxing inheritance lead to more Indian HNWIs seek refuge in nations with a friendlier tax regime?

Rishabh Kumar, assistant professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts does not think so. He says the migration of HNWIs from India started in 2011. “Indian HNWIs were exiting faster than the Chinese, which means their exit was driven by economic factors and not taxes alone.” He also points out that when the ultra-rich move out of India, they still leave their immoveable properties behind.

Beyond Inequality

A section of economists say the purpose of inheritance tax is not to bridge the wealth gap but address socio-economic issues. Amarendu Nandy, who teaches economics at the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) in Ranchi, says, “The primary objective of an inheritance tax is not necessarily to reduce inequality directly, but rather to prevent the unchecked accumulation and perpetuation of massive inherited wealth across generations, which can entrench economic disparities.”

The Piketty report, which draws a comparison between the era of the British Raj and India of today, calls India’s taxation system regressive, and claims India does not tax its rich enough.

Rohit Azad, who teaches economics at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) says inheritance tax can put India on a sounder growth path. “When you redistribute this income, it is going into the hands of people who actually consume more, which means there will be local demand.”

Talking about the recovery of the Indian economy following the pandemic, he says the recovery has come in the form of K-shaped growth. “The big cars are selling, and not the motorcycles and cycles,” he says, adding that an economy cannot sustain itself without a domestic market.

Azad’s argument is borne out by data. The share of private investment in the Indian economy, despite significant growth and a massive government capex push, has remained low because of weak consumption and demand. In the years between 2019 and 2024, the Union government’s share of investment in the economy has gone up by 226 per cent, while private investment has gone up by around 54 per cent.

Advocates of inheritance tax say if the affluent are not made to share their wealth, India could face major social, economic and political upheavals in the future. But a tax on wealth transferred to subsequent generations is a disincentive in the Indian context because of the significance of the family.

India has the third-highest number of family-run businesses in the world, following the United States and China. Family systems play a role in almost every industry sector in India—from micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) to the entertainment industry, and from the practice of law to the practice of medicine. The centuries-old social system of caste leads to families dominating professions and both wealth and poverty are transferred through generations.

The implementation of inheritance tax undermines the incentive for hard work and innovation, potentially hindering the country’s progress, says Srinath Sridharan, a public policy researcher and a corporate advisor.

Nandy of IIM-Ranchi says that while concerns over the potential disincentives of wealth accumulation are valid, they must be weighed against the broader societal benefits for a more equitable distribution of resources. He says, “Economic growth should not be pursued at the expense of perpetuating extreme wealth disparities, as such disparities can ultimately undermine long term social development and stability.”

Additionally, he also does not believe that a moderate inheritance tax will impede overall wealth accumulation or economic growth. “Most successful entrepreneurs and business leaders are primarily motivated by factors other than maximising inheritances for their descendants,” he says, adding that a well-designed inheritance tax system can provide exemptions and allowances that protect small and medium-sized inheritances, ensuring that only the largest concentrations of inherited wealth are taxed.

It remains to be seen if any subsequent government, at least in the near future, will implement an inheritance tax. The Congress party, whose advisor Pitroda first caused a flutter after discussing the tax system on television, has clarified that the party has no such plans. The Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP), in power now, has railed against the Congress for its advisor even suggesting such a measure. Therefore, the flummoxed family men of India, for now at least, can rest in ease.

It is also not clear whether inheritance tax is a sufficient anecdote to inequality. After all, the system has been tried, tested and has failed once. But burgeoning inequalities at a time when India’s demographic dividend is expected to peak may have an impact on the social order, which may then go one to affect the business environment in the country.

Unemployment among young Indians has been a rising concern for a few years now. A lack of liquidity has led to a decline in demand across sectors and the government’s ability to push growth by spending from its own exchequer is limited. There are economists who believe that the current rise in inequality is an aspect of an emerging economy, and once the economy matures, inequality will come down. But is letting inequality rise through the years when India hosts the youngest population on the planet a bright idea? Lawmakers who get elected on June 4, 2024, will decide.