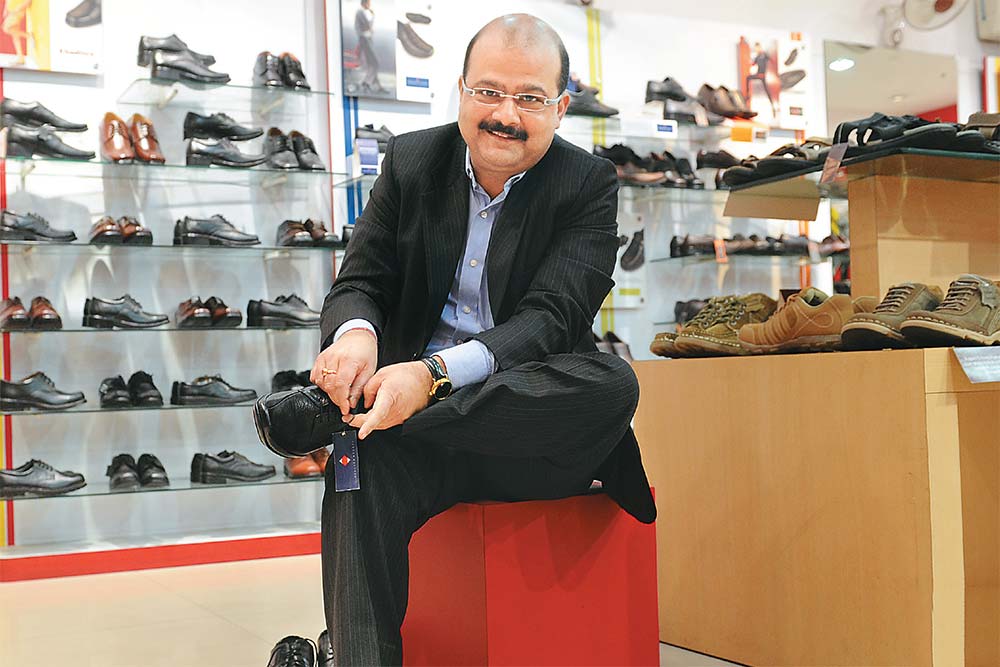

On a regular Sunday afternoon — when most people in Kolkata prefer a post-lunch siesta — Siddhartha Roy Burman and his wife quietly step out of their air-conditioned living room, and walk into one of Khadim’s many showrooms in the city. They give a pep talk to the staff, engage a customer in light conversation, or just observe how patrons behave in the store. They run the chain and despite its growth, refuse to let go of the family-run feel to it.

Roy Burman, the 50-year old managing director of Khadim India, knows from his three decades of experience in the footwear trade that the store floor is ground zero for his business.

Khadim caters to a loyal customer base nurtured over the past forty years. Average walk-in per day across 630-odd showrooms, both company-owned and that of franchises hovers around the 40,000 mark. Aggressive marketing and advertising spend (around ₹4 crore last fiscal) has helped create a strong brand recall in its catchment area, essentially across East and South India.

Khadim’s now has a presence in 21 states around the country. And its sales have jumped from ₹180 crore in FY08 to ₹320 crore in FY12, clocking a growth of 15% per annum. But maintaining profitability has been a challenge; the company ended FY12 with a net profit of ₹10.56 crore, a net margin of 3.3%. Around 70% of Khadim outlets are in Tier II and III towns, accounting for 60% of sales. “We want to be ₹500-crore company over the next two years, with a deeper pan-India presence,” says Ishani Ray, CFO, Khadim.

Rough cut

Khadim owes its origin to the octogenarian group chairman Satya Prasad Roy Burman who bought a 300 sq ft store on Chitpur road, Kolkata’s wholesale hub. The company was then known as KM Khadim, made popular by its presence in the wholesale footwear market. But that dingy little store is far from what Khadim is today. The makeover happened when Siddhartha joined the business in 1993. He convinced his father to diversify into retail.

The group made its retail debut in 1993 with three showrooms in Kolkata. Fast forward to 2012 — almost 85% of Khadim’s 630-odd stores are in the East and North East. The remaining are in the South, a market it entered in 1995 and did business worth ₹46 crore in FY12. A bulk of Khadim showrooms —around 520 — is managed by franchises, while the remaining are company-owned. However, the traditional wholesale business still accounts for around 60% of sales.

In the lure of better profitability, Khadim has been expanding its retail presence. It has not only doubled its franchised outlets but also ramped up company-owned stores. The result: sales through company-owned outlets are growing at a fast clip. Four years ago — in FY08 — sales through such outlets accounted for 32% of the pie — the figure now stands at 40%. The company also strengthened its central distribution network with a capex of ₹48 crore. And the results have started to show. Roy Burman declares, “If you take a train from Sealdah to the border districts of West Bengal, all stops on the way will have at least one Khadim store.” The group now boasts of being the biggest footwear chain in the East.

Well fitting

Analysts point out that Khadim’s USP has been its affordability plank. The positioning in the market is that of “value-for-money family footwear brand”. “The biggest strength of the brand is its reach coupled with customer loyalty,” says Pankaj Harlalka, executive director (Investment Banking), Microsec Capital, a financial services firm that worked with the group during an aborted public issue in 2008. Rival companies argue that despite running a tight ship, the Roy Burmans have nurtured trade relationships and maintained product quality.

Khadim has traditionally followed an asset-light model, sourcing a bulk of its raw materials and finished products — around 80% —from 300-odd third-party vendors, spread across East and North India. “Footwear is a fashion-driven and seasonal business. Outsourcing gives us flexibility to keep pace with fashion and design, without blocking capital and raw material in manufacturing,” explains CFO Ray. So, until recently, Khadim relied on its own manufacturing facility only for wash-and-wear and premium leather products, where maintaining quality is paramount.

Now Khadim is altering its strategy. To combat rising input costs, the management decided to set up another manufacturing facility in the North 24-Parganas district of West Bengal with an investment of ₹28 crore in 2011. Over the next year the new plant would augment annual production capacity by another 9 million pairs, as against the current capacity of 5.2 million.

“Given the affordability plank that we work on, our ability to pass on cost increases in the low value products (such as rubber chappals, PVC-based products) was limited. The incremental manufacturing capacity would largely be used to cater to low-value products and help keep costs under control,” says Ray.

Incidentally, Khadim’s average per pair MRP realisation grew steadily from ₹280 in FY08 to ₹375 in FY12, but that was just enough to take care of rising inputs costs. Even though the strategy to source bulk of products and raw material from third-party vendors would continue, share of in-house production would eventually go up from 20% to 35% as the new plant gets fully operational.

Road weary

However the ride, over the last two decades, has been anything but smooth. Egaro, its large-format lifestyle retail business, launched in 2007 with two stores in Kolkata, did not find takers, burning a hole in the balance sheet. The group pulled out of this line of business in 2010.

Subsequently, they made an entry into jewellery retail and notched up sales of ₹30 crore. But its momentum was derailed when Siddhartha’s brother, Partha, decided to go his own way. “The timing of the diversification and division of the management hampered its growth,” notes Microsec’s Harlalka. Rivals too concede that the group lost its impetus during that time.

The going is only getting tougher. Milind Karmarkar, research head, Dalal & Broacha, explains that it’s a challenge for mid-sized players when they come out of the “comfort zone”. Karmarkar explains that the unorganised sector is often an underestimated opponent. In the footwear market, organised players hold about 40% share of a market estimated at ₹25,000 crore.

Aggressive global footwear brands, too, are increasing their reach in terms of price and touch points across the country. And their biggest rival Bata is already double in terms of store count at 1,250.

But Khadim isn’t giving up. Ray feels the time-tested strengths of the organisation — wider market reach through dealer-distributor networks and company-owned outlets, the flexibility of trader-cum-manufacturing model, and the brand equity built over the years — would help the organisation withstand competitive pressures. However, pan-India growth would mean learning new tricks and unlearning a lot of things that Roy Burman has stood by. He is already changing track on a few counts. For the rest, Roy Burman and his wife will have to explore Sunday afternoon strolls outside of Kolkata for cues.

Just one email a week

Just one email a week