From the ramparts of the Red Fort this August 15, Prime Minister Narendra Modi proclaimed, “Our space sector was in shackles…we have liberated it from past restrictions.” The remark drew widespread agreement. The Modi administration has done much to give wings to India’s space ambitions. The Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) has notched multiple successes, and space-tech start-ups have mushroomed across the country.

The 2025 fiscal Union Budget has announced a Rs 1,000-crore venture capital fund for space-tech start-ups. Yet beneath the gleam of these successes, a humbling reality looms: the near absence of patient capital.

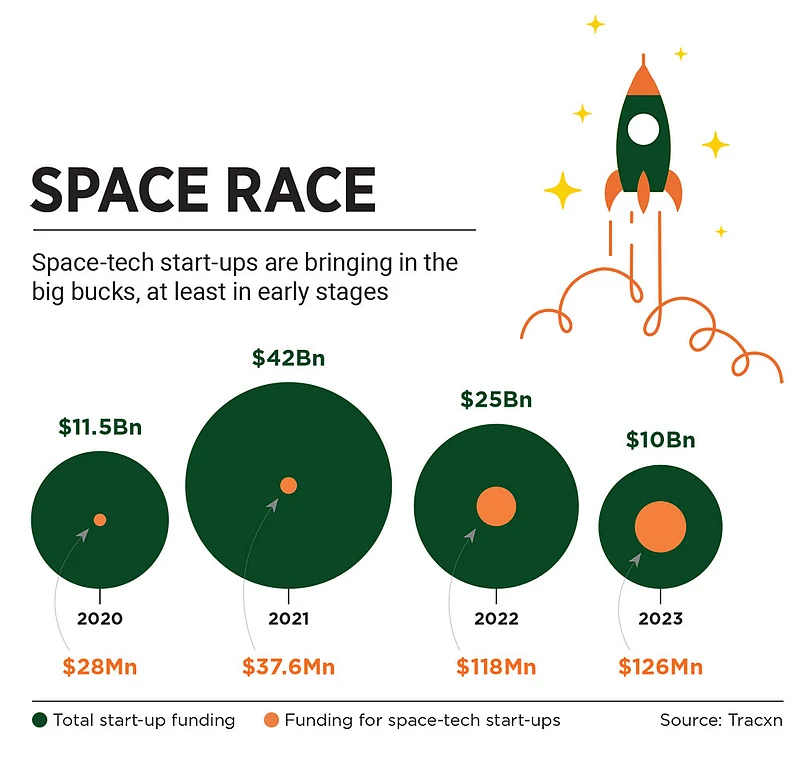

Indian space-tech start-ups have seen a surge of capital the past three years. Funding soared from $37.6mn in the 2021 fiscal to more than triple that in 2022, and to a 235% leap to $126mn in 2023, according to data from capital markets firm Tracxn. But a closer look reveals a troubling trend: of the $126mn, nearly 95% went to early-stage start-ups while a paltry sum trickled to late-stage companies. Early-stage investments dominate the funding landscape, with seed-stage start-ups receiving only a modest boost from $4.3mn in 2022 to $5.3mn in 2023. But late-stage start-ups—those most poised to deliver tangible results—are struggling for funds.

Failed Take-offs

India’s space-tech ecosystem is fertile ground for new ventures, yet not all are thriving. Dhruva Space, founded in 2012, is one of the country’s oldest space-tech start-ups, but it closed its Series A funding round 12 years later in April this year. Of the 200-odd space-tech start-ups in India today, only two—Ananth Technologies and MTAR Technologies have been listed on the stock exchange, and the sector has yet to produce a single unicorn.

Space-tech start-ups have seen funding soar from $37.6mn in 2021 to $126mn in 2023. But a closer look reveals a troubling trend

It is true that India’s space-tech sector is still young, having opened to private investment only a few years ago. Yet younger sectors have secured more funding and produced better financial outcomes. Artificial intelligence (AI), younger than space-tech in India, has already seen its first unicorn emerge—Bhavish Aggarwal’s Krutrim.

So, what is holding Indian space-tech start-ups back?

The key challenges are market access and the lack of government procurement, says Mahankali Srinivas Rao, chief executive of start-up enabler T-Hub, a firm that has worked with space-tech players such as Skyroot Aerospace and Dhruva Space.

India procures a large number of space-tech components from countries like the US, the United Kingdom, China and South Korea. Founders tell Outlook Business that despite building innovative products in India, the government often opts for legacy foreign brands. Government procurement is messy with a maze of bureaucracy. Tiny start-ups lose out.

“Government procurement of domestically produced space-tech solutions can provide start-ups with a reliable market enabling them to scale their innovations effectively. Prioritising the purchase of homegrown technology can create a sustainable market for local companies,” says Rao.

For space-tech start-ups, the government is an important stakeholder. Ronak Kumar Samantray, founder of space-tech start-up TakeMe2Space, says most space-tech start-ups in India build satellites and there are only two customers for them—the government or big telecommunication companies. Samantray acknowledges that India is a small market for direct Earth observation customers except for the government, but he argues communication could be an opportunity for India’s space-tech start-ups.

“India is a large consumer of communication products which is why Airtel and Reliance have entered the market. But these companies buy the technology from outside instead of building it in India or acquiring an emerging satellite communications company,” Samantray adds.

A founder of a space-tech start-up being incubated at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Kanpur says on condition of anonymity that major space-tech start-ups are able to generate initial hype but eventually slow down due to a lack of market and infrastructure.

Impatient Capital

To position India as a leading space-tech market globally, industry stakeholders are calling for substantial infrastructure development, including the establishment of new launch facilities, testing and integration centres. Rao of T-Hub says space-tech start-ups need a lot of money before they can start making money. This makes it hard to obtain funding from investors because most investors are unwilling to be patient for the number of years a space-tech company needs to succeed. Venture capitalists (VCs) have a five–seven-year return cycle which is difficult for space-tech start-ups to meet.

Better Times Ahead?

There is reason to hope. The prime minister recently said that India hopes to have its own space station by 2025. Along with the Rs 1,000-crore VC fund announcement in the Budget, industry stakeholders see light at the end of the tunnel. After all, government policy is crucial in driving space-tech’s growth from its current valuation of $8.4bn to $44bn by 2033. Industry watchers say the government is expecting investments of around $22bn in the space sector over the next decade.

Indian Space Association (ISpA) director general AK Bhatt, a former lieutenant general in the Indian Army, says Indian space-tech start-ups have not reached the stage of producing their final products yet as innovation in technology continues along with reforms in policy. “Once start-ups start moving towards building their final products making use of the FDI [foreign direct investment] coming in and enhanced technology, we will see assurance from the market both in terms of international clientele and late-stage funding.”

While early-stage capital is not a problem for Indian space-tech start-ups, the need of the hour is patient capital. Scaling and commercialising Indian space-tech will depend on the government’s willingness to give homegrown companies a fighting chance. If the current stream of reforms work, for Indian space-tech, even the sky is no limit.