In the winter of 2011, the world watched as international crude prices surged amid the chill of economic uncertainty, casting a shadow of concern over the global economy. For India, led by the then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh of the Congress, it was a time of existential crisis. Squeezed between surly allies, economist-turned-statesman Singh found himself navigating treacherous political waters.

One such ally was Mamata Banerjee, Trinamool Congress (TMC) supremo and chief minister of West Bengal. Her threats to withdraw support from the central government sent shockwaves through the corridors of power. The Arab Spring had unleashed a wave of unrest that reverberated across the globe, sending crude prices soaring. India, heavily reliant on oil imports, felt the sting acutely, grappling with a ballooning current account deficit.

But understanding and empathy seemed in short supply among the members of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA). Singh, who once rescued India from the brink of bankruptcy during his tenure as finance minister in the P.V. Narasimha Rao government (1991–96), found himself besieged by political adversaries who seemed unwilling to acknowledge the harsh economic realities confronting the nation.

Faced with mounting pressure and the imminent threat of his government collapsing, Singh made the difficult choice of slashing petrol prices for end consumers by boosting subsidies, a move fraught with both political and economic implications. The UPA’s second term (2009–14) saw India’s total expenditure on fuel subsidies shoot up from Rs 2,852 crore to Rs 85,378 crore.

Adding to the turmoil, the UPA government faced numerous corruption charges, with several key allies accused of involvement in scandals. Given the heavy burden of coalition dharma, Singh was allegedly forced to look the other way as critics labelled him ‘Moun (quiet) Mohan’.

Soon enough, the UPA government found itself in a state of policy paralysis, unable to make key policy decisions while battling corruption scandals, bureaucratic inertia and loss of investor confidence at the same time. Seizing this opportunity, Narendra Modi, the chief minister of Gujarat known for his pro-business stance, rose to power. Coalition politics had earned a bad name in the country.

For the next 10 years, Modi held on to power with brute majority in Parliament, reminding the electorate at every juncture the need for a majority government to get India its rightful place in the global economy. For supporters of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the two terms (2014–24) under Modi laid down a solid foundation for the country’s economic growth.

“While sticking to macro-economic parameters like fiscal deficit target and inflation target, the government achieved success in many other places. The capex-led infrastructure push has reduced logistics costs, increased overall connectivity and improved ease of living for many. If you look at manufacturing, the PLI [production-linked incentive] scheme has taken off in many segments,” says Gopal Krishna Agarwal, BJP’s national spokesperson on economic affairs.

The strong majority enjoyed by the BJP-led government for 10 years emboldened its finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, to claim that the government will undertake major reforms in its third term at the Centre. “I will underline the fact that the reforms will touch on all the factors of production. Be it your land, be it your labour, be it your capital,” she had said in February at a Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) event.

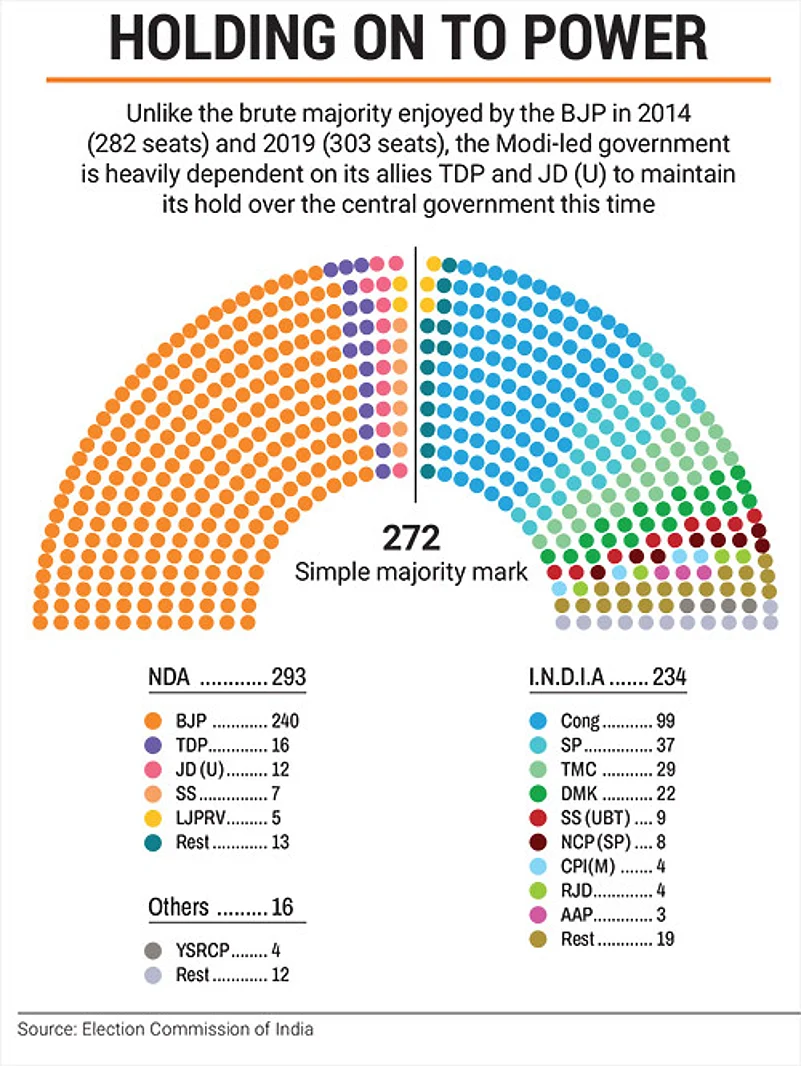

India’s political economy finds itself at a crossroads once again. The recently held parliamentary elections showed that BJP’s confidence in its policymaking did not reflect in the people’s mandate. While the party predicted itself to win over 350 seats in the 543-member Lok Sabha, it could manage only 240.

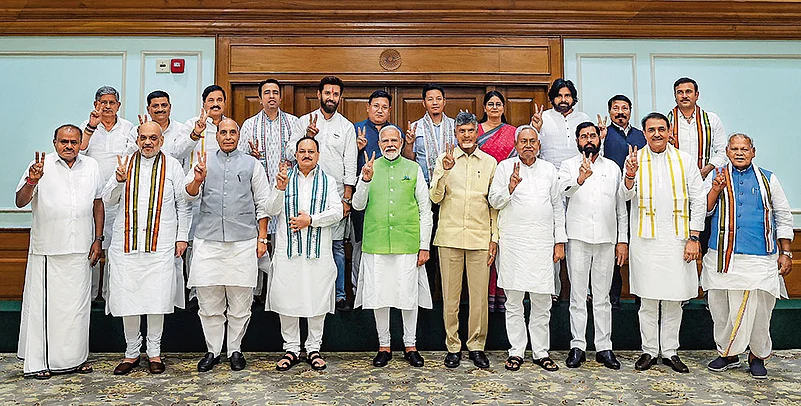

The BJP-led government has embarked on a historic third term. But this time, Modi finds himself in a precarious position, reliant on the support of two formidable regional leaders: N. Chandrababu Naidu of Telugu Desam Party (TDP) in Andhra Pradesh and Nitish Kumar of Janata Dal (United)—JD (U)—

in Bihar.

The new government’s economic agenda is now contingent upon the goodwill of politicians who have previously levelled accusations of corruption and partisanship against Modi. It is a delicate dance of power and compromise.

The Subsidy Strain

Modi’s formula for political success has been his hard pitch for exponential growth of the Indian economy. And his chosen path involves fiscal consolidation and a continuous push towards making the country a manufacturing hub.

Both could be sacrificed at the altar of coalition politics.

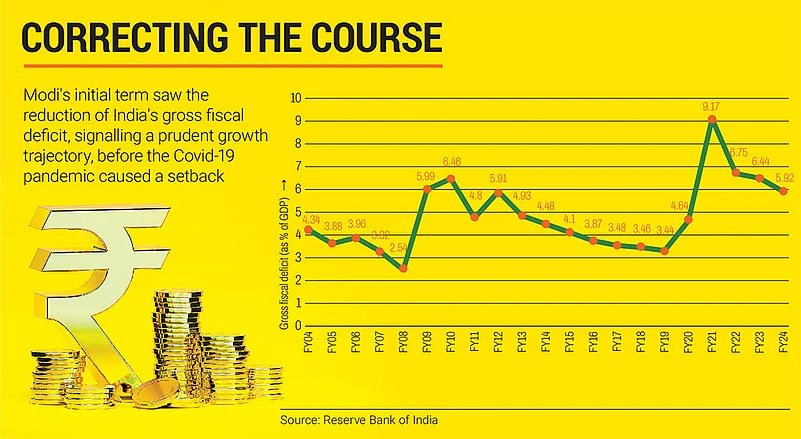

Since ascending to the office of prime minister a decade ago, Modi has been relentless in his approach towards fiscal consolidation. Before BJP took over at the Centre, India’s net fiscal deficit as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) was 4.4% for 2013–14. In his first term as PM, Modi managed to keep it under 4% for five straight years.

With no compunctions of irate allies, a key ingredient in this achievement was the bold decision of decontrolling the price of petrol and diesel, a move aimed at reducing fuel subsidies. By tethering fuel prices to the volatile fluctuations of the international crude oil market, the Modi government capitalised on the dramatic plunge in crude oil prices in 2016 to $28 per barrel, bolstering government revenue in the process.

Even when the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic sent global oil prices crashing in 2020, the government hiked excise duty on petrol by Rs 13 per litre and by Rs 16 on diesel in two installments between March 2020 and May 2020, a move unthinkable for Manmohan Singh a decade ago as he jostled with allies.

However, for the Modi-government this provided a hefty revenue stream, where it earned over Rs 4.92 lakh crore in 2021–22 from the petroleum sector duties and taxes, as opposed to the Rs 1.72 lakh crore it earned in 2014–15. It also cut down its subsidy bill for food and fertilisers during its very first term.

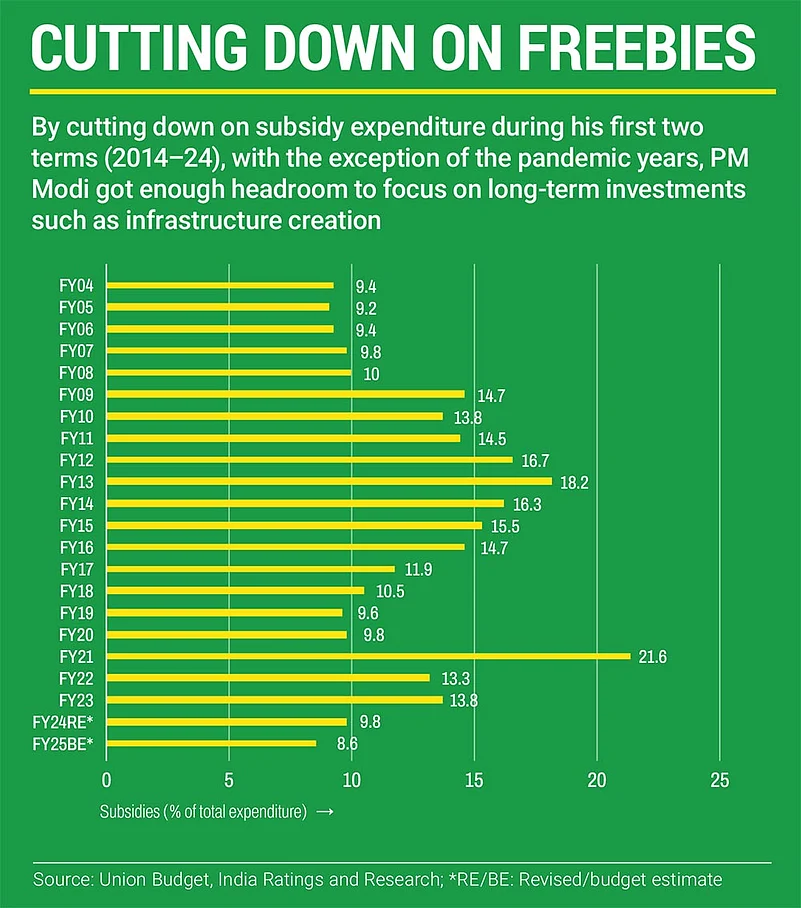

These newfound funds were channelled into a sweeping infrastructure overhaul, marking a significant investment in the nation's future. Consequently, the Union government’s subsidy bill as a share of total expenditure fell from 16.3% in 2013–14 to 9.8% by 2019–20. Despite the pandemic-induced spike in the following couple of years, this share is estimated to go down further to 8.6% in 2024–25, as per budget estimates.

In a way, this highlighted the BJP-led government’s commitment to fiscal prudence and its resilience against populist demands in its first two terms. But India’s political history gives enough reasons to doubt whether such a curtailing of subsidy expenditure can survive the pressures of a coalition government.

“When I was finance minister in the coalition government [1998–2002], the coalition partners were not concerned if we were building national highways or rural roads or spending on airports and ports. They were, in fact, happy. But what bothered them was the fact that we were trying to reduce subsidies on food grains and petroleum products. Therefore, I was under constant pressure, and one could not touch them [subsidies] because the coalition partners would get angry,” recalls Yashwant Sinha, who was a BJP leader for over two decades.

Notably, the NDA government (1998–2004) led by BJP’s Atal Bihari Vajpayee counted JD (U) as an important ally while Naidu’s TDP provided ‘outside support’ to the government. Sinha's apprehensions about the coalition-induced compromises are worth noting because both TDP and JD (U) have quit BJP-led alliances in the past.

Payback Time?

In the lead-up to the state assembly elections in Andhra Pradesh, which coincided with the parliamentary elections, TDP’s populist promises included free liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) cylinders for every eligible household, Rs 20,000 investment support for farmers, creation of 2 million jobs, free bus rides for women and a monthly unemployment allowance of Rs 3,000 per month. Modi has repeatedly criticised such populism disdainfully calling these “revdis” (freebies) that lead down the path of fiscal indiscipline.

“As a government it is our primary responsibility to take care of people. In the past five years, things have gone very badly, and the standard of living has come down for common people. To revive that, we have to give welfare schemes. Development and welfare are two wheels of the same cycle,” says Jyothsna Tirunagari, TDP’s national spokesperson.

Revdi or not, by a political twist with the valuable contribution of 16 seats to the NDA’s overall tally of 293, TDP can now demand the BJP-led Centre’s assistance in delivering these expensive promises.

The BJP’s own electoral fortunes can also force the hand of the Union government when it comes to populist welfare schemes. In a departure from the norm followed by most governments in an election year, the Modi government presented a budget devoid of populist measures during the vote on account—an interim budget presented before the dissolution of Parliament at the end of its five-year term—in February this year.

But what followed was an election result that surprised many. “It is possible that BJP can learn a wrong lesson from the election results. There can be a feeling that because they did not announce any populist measure in the interim budget, they will have to rethink that in the coming July budget,” says Rahul Verma, fellow at Centre for Policy Research, a Delhi-based policy think-tank.

As the new government draws up its first budget, BJP will be mindful of the formidable challenge in the upcoming state elections, slated to unfold between November 2024 and the following year. The crucial battlegrounds include Haryana, Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Delhi and Bihar. As far as TDP and JD (U) are concerned, the upcoming budget will also present a clear picture of how much Modi is willing to bow to their demands.

“There must be some bargaining chip that JD (U) and TDP must have kept on their side. They have not got big ministries. Then the compromise would be on a special package for the state. I think the parties will try to extract that from the BJP,” says Verma.

Two 'Special’ States

Both TDP and JD (U) have a long history of demanding “special category status” (SCS) for their respective states for similar reasons. Ever since the state of Jharkhand was carved out of the mineral-rich regions of Bihar at the turn of the century, the latter has felt that it has been dealt a raw deal.

The bifurcation of Andhra Pradesh in 2014, where the new state Telangana got to retain the information technology hub of Hyderabad as its capital, served as a trigger for special status demand in the south Indian state.

In 2018, the TDP had even officially pulled out of the then Modi government after Andhra Pradesh was denied its SCS demand. Naidu reportedly wrote to home minister, Amit Shah, saying that the TDP had joined the NDA with the expectation that the people of Andhra Pradesh “will get justice”, meaning that the state will get SCS, adding that since being in alliance with the BJP was not serving that purpose, he felt it was pointless to continue.

JD (U)’s Nitish Kumar also reiterated Bihar’s demand for SCS when he quit the NDA for a brief time between 2022 and 2024. And with Bihar set to go to polls next year, the BJP might find it difficult to turn this demand down.

The special status allows states to receive more funds from the Centre for centrally sponsored schemes while also opening the door to additional grants. This has historically been given to northeastern and hill states that have traditionally lagged in terms of economic growth.

However, the 14th Finance Commission had put an end to the practice of SCS for states. Now that Naidu and Kumar have a ‘kingmaker’ role in the new government, can they push for a revival of the practice?

“It is not just special category status, there are a lot of other things that we can get done. If we think a special financial package must be given, we will put it forward. If we require any other benefits like special economic zones, we will discuss that,” says TDP’s Tirunagari, while clarifying that the issue of special status is “not wrapped up”.

“TDP will demand its pound of flesh for Andhra Pradesh,” says Sinha, while recalling an incident from 2001 which demonstrates the bargaining power of TDP chief Naidu. “When we were setting up IRDA [Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India], I remember Chandrababu Naidu came to me, and he said that the headquarters of IRDA should be in Hyderabad. He also insisted that the first chairman of IRDA should be an Andhra cadre officer of his choice. We had to concede both,” narrates Sinha. In 2001, the insurance regulator’s headquarters was shifted from New Delhi to Hyderabad.

The former finance minister reckons that Naidu will bargain for emerging industries like semiconductors, electric vehicles or renewable energy this time around. “Andhra Pradesh will have to be the new Gujarat, that is what they will demand. Andhra will be competing with Gujarat at every step,” he adds.

In terms of industrial might, Gujarat, which has been a BJP stronghold for decades, currently tops the list of states with 18% of the overall factory output in the country.

Giving AP special status will have a domino effect with other states clamouring for similar benefits. While Gujarat's prosperity was at a time when Modi headed the state, the case for UP's economic rise is often criticised as a case of the Centre's partisanship. Compounding PM Modi's special-status-to-AP problem is the north versus south debate still reverberating in parts of the country.

Reformist Dreams

To make sense of the changes that the NDA wants to bring about, it is worth looking at some of its decisive actions from the past 10 years. Although the Goods and Services Tax (GST) had been in the pipeline for very long, it took the brute majority of the Modi government to finally bring in the new taxation structure in 2017. Replacing a complex web of indirect taxes with a single nationwide tax, the GST reform enabled a unified national market.

This was followed up by corporate tax cuts in 2019 which saw the standard rate brought down from 30% to 22% for existing companies and 15% for new manufacturing companies. Other streamlining measures in the area of permits and tax filings significantly improved the ease-of-doing-business (EoDB) in the country. As a result, India’s ranking in the World Bank’s EoDB index improved from 142 in 2014 to 63 in 2020.

The Modi government’s message was clear: By removing hurdles from the path of private capital, the state wants to create a conducive market for investments that can generate economic activity, create employment and enable consumption.

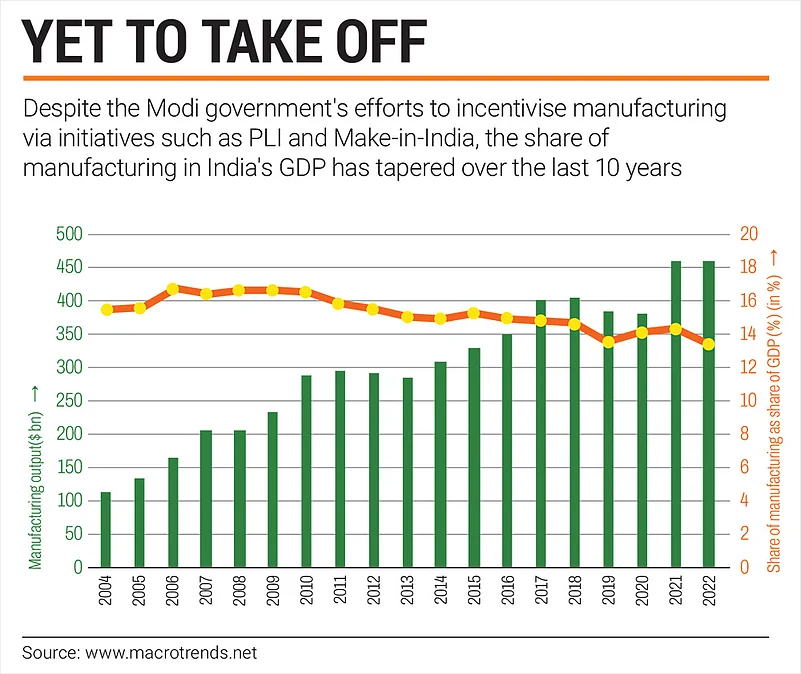

When it comes to the choice on what kind of industries to focus on, the BJP-led government has taken a clear stance in favour of manufacturing. “Our policies such as Make in India and PLI have significantly increased manufacturing activities. We recognise that manufacturing presents huge potential for employment creation. We will make Bharat a trusted global manufacturing hub,” promised the BJP manifesto for 2024 Lok Sabha elections.

Arvind Virmani, member of the government policy think-tank NITI Aayog, and former chief economic adviser to the Centre, believes that it is a golden opportunity for India to become part of global value chains.

As large sections of the developed world attempt to de-risk its supply chain beyond the manufacturing hub of China, there is some optimism around India’s prospects as a manufacturer for the world. But others, who do not share this optimism, argue that India should play to its existing strengths and focus on services exports to improve its position in global trade.

Virmani argues that it is not an either-or situation. “India is [made up of] 28 states. We are not one [South] Korea or Taiwan or Thailand. We are 28 Thailands. Some will focus on agriculture, some on manufacturing and some on services. Why do you have to choose? There are different stages of development,” he says.

But to make any meaningful addition to India’s global trade prospects, policymakers suggest that more reforms are needed. Virmani adds, “The governments between 1991 and 2014 have tried to remove the negatives, but in the past 10 years, we have focused more on creating a lot of positives. But this does not mean that we do not have negatives to remove that discourage manufacturing,” alluding to reforms around land and labour.

Soon after coming to power in 2014, the Modi government had issued an ordinance to amend the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (RFCTLARR) Act, 2013. This would have allowed relaxations around land acquisition processes. However, faced with widespread protests, the amendments were put in abeyance and are likely to remain as such.

Before the recent assembly elections in Andhra Pradesh, the TDP had picked a fight against former

CM Jagan Mohan Reddy’s land reform law. The Andhra Pradesh Land Titling Act (APLTA), 2023, modelled after Centre’s proposed land reforms, was denounced as a “Land Grabbing Act” by Chandrababu Naidu.

In fact, in the joint manifesto shared by TDP and its local alliance partner Jana Sena Party (JSP), it was promised that they would repeal APLTA. Curiously, BJP did not publicly endorse the joint manifesto even though TDP and JSP are its electoral partners in AP, clearly pointing to a divergence of views on matters like land reform and welfare measures.

Even with JD (U), land reforms have been a tricky affair. Although Nitish Kumar had once supported liberalised land reforms as a necessary policy measure, his party has been a strong opponent of the BJP-led government’s 2015 amendments to the RFCTLARR Act. Having termed the amended law as a “black law”, Nitish Kumar even took part in a 24-hour fast in early 2015 to protest the contentious land acquisition law. "The land acquisition amendment bill is anti-farmer and anti-people,” Kumar had

said then.

Similarly, the Centre had to roll back its three farm laws in 2021 after a year-long protest by farmers’ groups. The laws sought to deregulate various agricultural markets while legitimising practices like contract farming.

India’s agricultural yields are among the lowest compared to its peers, necessitating modern farming practices that rely on private capital. There was hope that a stronger BJP government would persuade state governments to implement reforms that could uplift the millions of Indians dependent on agriculture. However, achieving this goal appears increasingly challenging at present.

Reforms and Allies

Ahead of the 2024 election results, senior government officials and industry bodies appeared enthusiastic about major land and labour reforms being executed by the incoming NDA government. However, the surprisingly low number of seats for BJP has now thrown a spanner in the works.

Instead of anticipating quick actions as part of a purported 100-day agenda, there is a cloud of suspicion on whether the BJP can push through reforms given its coalition constraints. After all, if the BJP failed to push through contentious reforms during the first two terms of strong majority, how can they hope for such drastic moves under a coalition government?

“In our history, most economic reforms have happened under minority governments. When you have to get a bill passed in the Lok Sabha, you check with your allies, and this is not something that is required in the case of a brute majority. The allies come from different quarters of the country and represent various group interests. All kinds of consultations and bargains happen in this process.” says Verma of CPR, making a case for the possibility of major economic reforms by the new NDA government.

Reformist governments, like that of Congress leader P.V. Narasimha Rao in the early 1990s, have enacted major changes in the country’s economic growth story while negotiating the intricacies of coalition politics. Governments that enjoy single majority in Parliament, like the BJP did, have also had to back down on the face of popular resistance. If anything, this is illustrative of the complexity of India’s political economy.

The new NDA government that took charge on June 9 made it clear that policy continuity is at the top of its agenda for the new term and in a clear signal Modi has kept the leadership in key ministries such as home, finance, commerce, defence and external affairs unchanged.

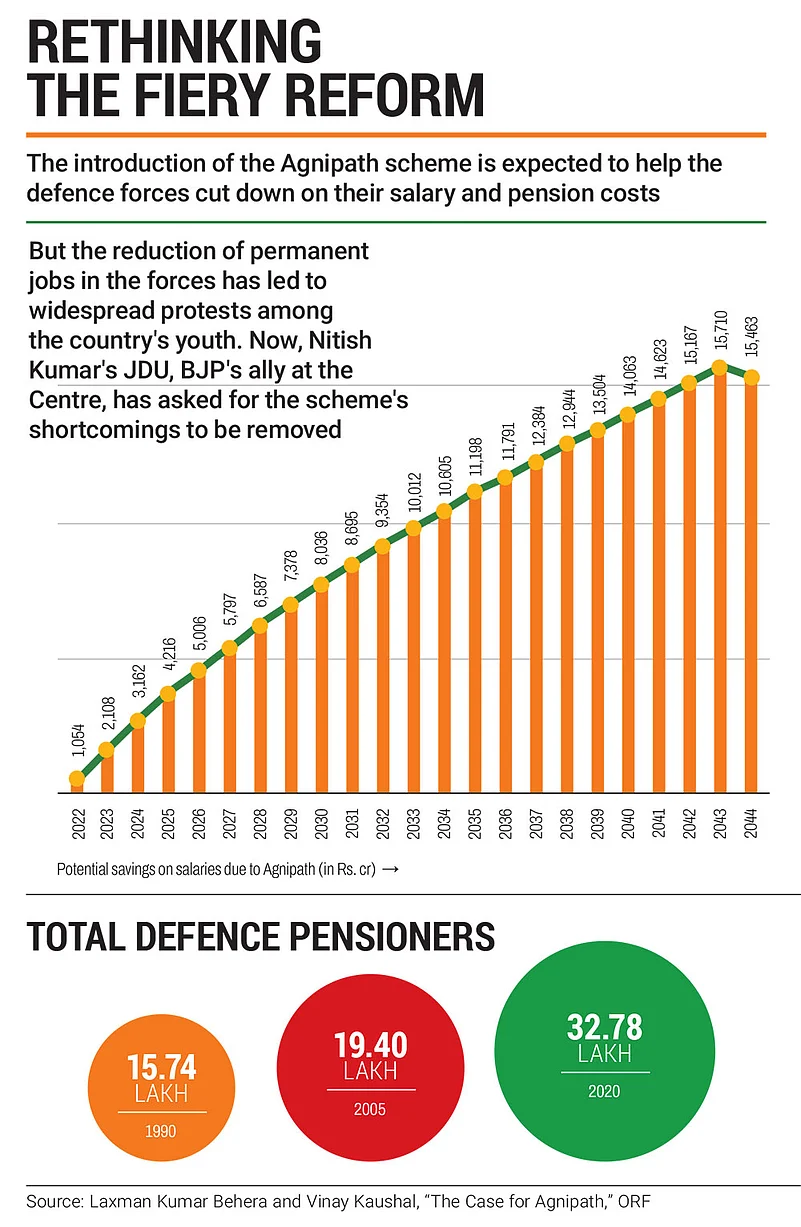

At the same time, the BJP is already having to confront the possibility of rethinking its reform measures due to pressure from its alliance partners. Soon after the results, senior JD (U) leader K.C. Tyagi spoke about the need to reconsider the Agnipath scheme brought about by the previous government.

“A section of voters has been upset over the Agnipath scheme. Our party wants those shortcomings which have been questioned by the public to be discussed in detail and removed,” he said.

Opposition parties had already positioned the criticism against the scheme as a broader attack on the government’s failure to generate sufficient jobs for the country’s youth. Now, with unemployment and low consumption already fuelling anti-incumbency among large sections of the BJP voter base, the Modi-led party will have to think twice before engaging in any provocative measures. With BJP’s political invincibility being called into question by the electorate, the party needs to be careful in risking mass agitations like the ones against the farm bills or the Agnipath scheme.

Soon after the results, psephologist and social activist Yogendra Yadav, whose poll prediction was far more accurate than exit poll surveyors, claimed that as a result of BJP’s weakening hold over the Centre, “protests, movements and andolans in this country will get stronger”.

Stormy Beginnings

Within weeks of taking charge, Modi’s third term is already facing disaffection from the public over issues like the Bengal train tragedy, the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) scam and the cancellation of University Grants Commission–National Eligibility Test (UGC–NET) exams following question paper leaks. The latter two have affected around 3.3 million students, who feel that they are

victims of corruption and government inefficiency.

Not only does this fuel discontent among the youth, but it also furthers the criticism against BJP’s centralising tendency seen in sectors like education, which is part of the Constitution’s concurrent list.

It is worth remembering that the downfall of the second UPA government was caused by more than just differences within the alliance. “The Congress-led government was under a lot of pressure because of the mass movements that had started happening. That period witnessed the maximum number of mass mobilisations since the 1989–91 period which saw mobilisations around caste, religion and corruption. So, they [Congress] had to become more accommodative of their allies because of that pressure as well,” says Verma.

Results 2024 have cemented the end of centralisation, at least for the time being, as the way to administer India. This could be the beginning of yet another era of coalition politics. And at the heart of it lies the dharma of decentralisation, in stark contrast to Modi’s political ideals.

So, the question remains: Can Modi remain steadfast with his reformist agenda in the face of truant allies, or will he succumb to the pressures of coalition, a fate endured by his predecessor Manmohan Singh?

(With inputs from Parth Singh)