Narendra Modi burst in on the national scene in May 2014 with a promise of reforming the business environment in India, the way his supporters claimed he had done in Gujarat during his long stint as its chief minister. However, in the next two years, his party and government were besieged from all sides.The then rising star of Indian politics Arvind Kejriwal annihilated the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the Delhi assembly election in February 2015. In April, the then vice-president of the Congress Rahul Gandhi made his now-famous “suit-boot ki sarkar” jibe at the government. By August, the opposition prevailed over the government and forced a withdrawal of the contentious amendments to the Land Acquisition Act of 2013 that were seen as anti-farmer and pro-business. If this was not all, by the time the year ended, an aggressive Supreme Court had dealt a decisive blow to the government by striking down the ambitious National Judicial Appointments Commission Act which would have given the executive legal means to influence judicial postings. In the next year, Modi was a changed man.

His government took two major and decisive gambles on the economy which redefined his governance style and, in many ways, whose effects are still being felt in different measures. In 2017, after years of protracted negotiations in various committees, Parliament welcomed the goods and services tax (GST) regime in a special midnight session which mimicked the famous midnight session of India’s independence. The government knew the importance of the GST in the economic history of the country, and the prime minister, playing on his penchant for expansions of acronyms, proclaimed it a “good and simple tax”. Little would the Centre have realised then that both these epithets would become contentious in years to come.

The Centre had managed to convince a majority of state governments to agree on a taxation idea that required the latter to give up their fiscal autonomy with a promise for a better, but composite, future. The promised better future would have hinged on the success of cooperative federalism through a countrywide unified indirect tax.

The State of Power Games

The passage of the bill and its subsequent ratification in state assemblies, the latter being a constitutional requirement, allowed the GST to subsume eight different types of existing taxes levied by state governments to create the harmonised tax system. Since the states did not want to surrender their right to raise tax revenue, the Centre seduced them with an irresistible deal. The balance of power between the Centre and states tilted that much more in favour of the former at the successful completion of this exercise.

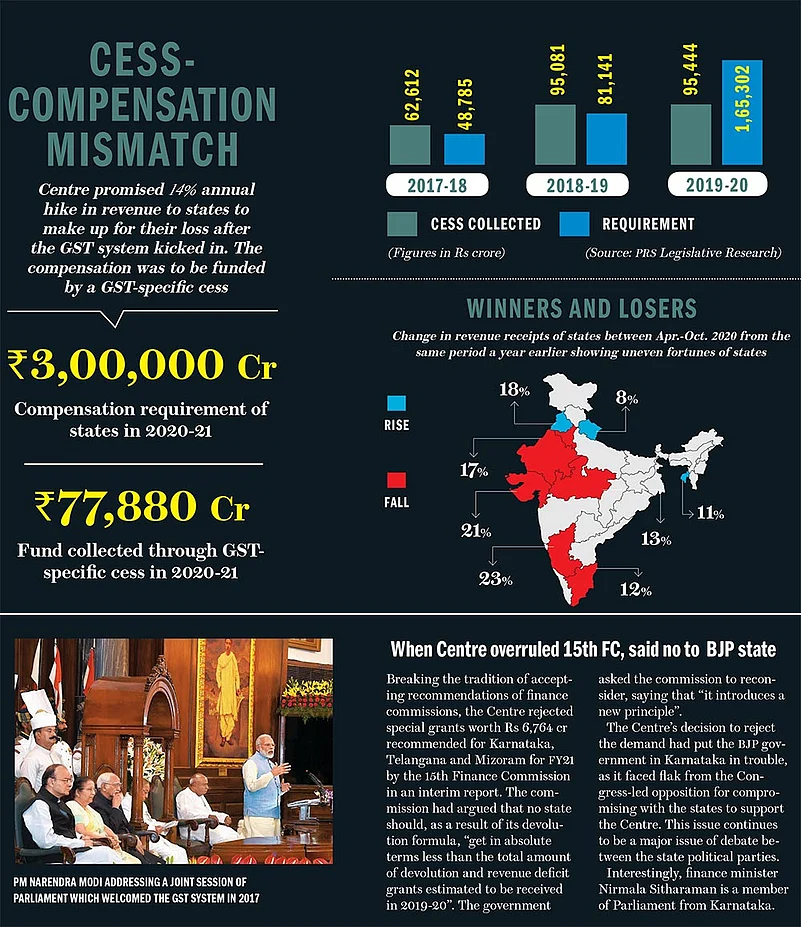

The Centre guaranteed a 14% annual growth rate in GST revenue to the states with 2015–16 as the base financial year for a period of five years starting July 2017. The states thought that since they had the annual revenue growth rate of less than 10% in the pre-GST era, the Centre’s offer made sense. The Centre’s ability to present the GST regime purely as a revenue mobilisation idea kept the stakes on power tussle low. Even when the number of state assemblies where the BJP ruled the house was not at its peak, the then finance minister Arun Jaitley was able to impress upon a majority of states to endorse the new GST regime by showing the revenue potential of an achhe din economy.

It is not that everyone bought into the Centre’s argument. The Congress pussyfooted on its support, sometimes calling the GST regime former prime minister Manmohan Singh’s baby and other times faulting it for bad framework and having too many tax slabs. The Left was more categorial in its denunciation of the regime, particularly its government in Kerala. Its then finance minister T.M. Thomas Isaac saw in the Centre’s design an attack on the idea of federalism in the GST regime.

Betrayal and Backlash

There were no early warning signs of brewing discontent against the new taxation system. Things stayed rosy in the first two years of the promised riches of the mandatory five years, as the Centre fulfilled its promise of providing the requisite GST compensation to states. The Centre created the headroom to be profligate by heaping compensation cess on sin goods and petroleum products.

Prime Minister Modi had developed a strong liking for creating disruptions by then, both in the political as well as economic spheres. Before the GST system could kick in, Modi shocked the economy with the sudden and massive shake-up of demonetisation, the other decisive gamble on the economy. Till date the government does not count it as a negative disruption. However, economists of certain persuasion claim that it had an obstructive impact on the economy. While the jury is still out on the issue, the economic slowdown of the Indian economy since 2019 is an officially recorded fact. It brought the new taxation system under stress and curtailed the Centre’s ability to keep its promise to the states, forcing it to provide funds only in the form of loans.

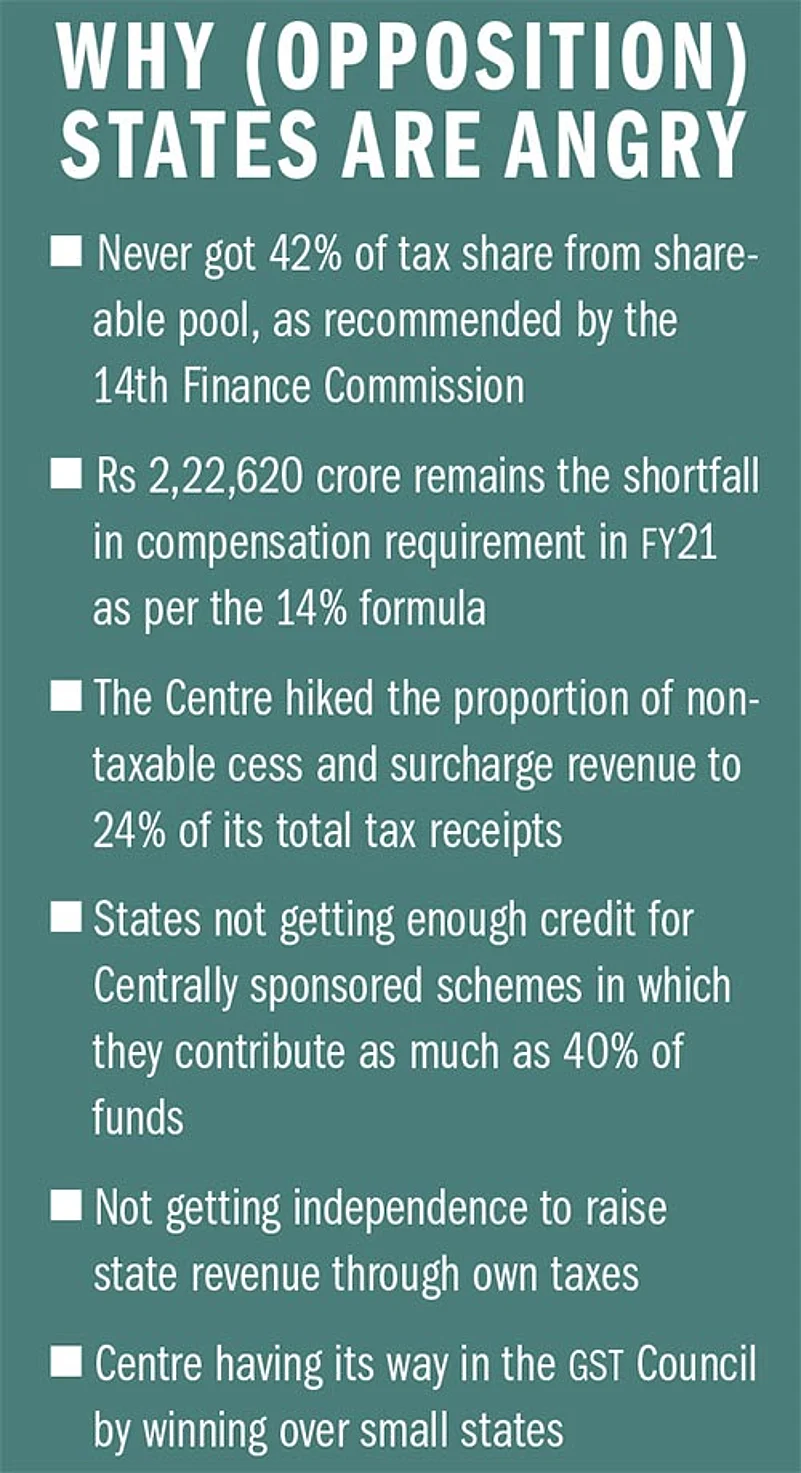

Nobody likes to be short-changed, and certainly not by someone they see as a domineering political adversary. Realising that they were offered a raw deal by the Centre from 2019 onwards, a majority of the non-BJP states, like Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Chhattisgarh, Kerala, West Bengal, Delhi and Punjab, have come together to demand an extension of the GST compensation period by five years when the existing period ends this year. “The Centre owes Rs 13,000 crore to Chhattisgarh against disbursement and compensation under several Central taxes. It has withheld these payments for three years now. The Centre, also, has to pay over Rs 4,000 crore [to us] as coal compensation as per the directions of the Supreme Court. The Centre has been pushing us to take loans in lieu of the compensation for the goods and services tax. It was supposed to extend financial assistance [to states] in the wake of the pandemic, but it has been saddling states with debt,” Chhattisgarh chief minister Bhupesh Baghel says.

States feel that now that they do not have any power to fill the shortfall in revenue from within the state by levying local taxes, the Centre should honour not just the commitment to pay GST arrears, it should be liberal with allocations under other federal acts. For example, they want it to increase the borrowing limit under the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act to 5% of a state’s gross domestic product from the current 4%. They also want the Centre to hike its contribution for Centrally sponsored schemes.

While GST revenues have started to pick up in the recent months, the Centre is unlikely to give in to the demand. Its clue can be found in the opinion of BJP national spokesperson Gopal Krishna Agarwal. He blames the states for not curbing their prodigal behaviour, saying, “It is the responsibility of the states to keep their finances under check in accordance with the mandate of the FRBM Act. All the freebies that are announced by the states should be given keeping in mind their resources.”

There are also voices that feel that a new system needs time to stabilise and both sides need to honour the spirit of the GST legislation. Sumit Bose, a former Union finance secretary who retired in March 2014 and then was appointed a member of the Expenditure Management Commission, feels that the GST system is an important issue and cannot be allowed to be derailed over the issue of the extension of compensation period. He hopes that both sides will arrive at a solution soon. He says, "Both the Centre and the states have given up some of their taxation powers to arrive at the GST compact. The states have given up significantly more of their powers. Despite the rhetoric of politics, both the Centre and the states are committed to this major reform. The Centre has to take the lead in allaying any fears of the states." He adds another layer to the debate. He feels that even the third tier of the governance structure should have a share in the GST collections. He says, "A share of the GST, however small to begin with, must go to the third tier of local governments if fiscal federalism is to be strengthened."

Deteriorating State Finances

Given the fact that the states are now largely dependent on the Centre for funds as against the situation in the pre-GST era, they are feeling the heat of a slowing economy just as the Centre is. But, there is an increasing divergence between the condition of their finances in these tough times.

According to the data provided by the credit agency ICRA, the Centre improved its fiscal deficit in the April-October 2021 period at Rs 5.5 trillion, as against the deficit of Rs 7.2 trillion in the pre-pandemic period (April-October 2019). The ratings agency expects the Centre’s net revenue receipts to exceed the budget estimate by Rs 1.7 trillion on the back of higher GST collections and surplus transfer from the central bank.

On the other hand, 22 state governments reported a fiscal deficit of Rs 3.2 trillion in the first seven months of FY22, up from the pre-Covid level of Rs 2.3 trillion. The cause of higher deficit was a meagre increase of 4.2% in the tax and non-tax revenue of state governments compared to the pre-pandemic period. Clearly, the Centre has used some tricks to improve its finances, passing on a large burden of the slowdown to the states.

A study by think tank PRS Legislative Research estimates the states to spend 12.8% of their revenue receipts on interest payments in 2021-22. This is higher than the recommended level of 10% by the 15th Finance Commission.

Centre’s Schemes

Extending the GST compensation period by another five years will be difficult for the Centre, and the states know this well. But, they may be using the GST issue as a bargaining tool to make up for the anomaly introduced by the Centre since the implementation of the recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission that required the Centre to share 42% of the divisible pool of taxes with states as against 32% recommended by the 13th Finance Commission.

In February 2015, the Centre agreed to increase the share of the divisible pool of taxes with states as per the suggestions of the 14th Finance Commission.

M. Govinda Rao, a member of the 14th Finance Commission, explained the commission’s reason for the increase. He says, “The Centre was uncomfortable with the recommendation to increase the states’ share in the divisible pool from 32% made by the 13th Finance Commission to 42% made by the 14th Finance Commission. The increase was recommended because the commission’s mandate was to take into account both plan and non-plan expenditure requirements of the states as against the mandate of considering only non-plan requirements by the previous commission. The plan grants constituted about 5.5% of the divisible pool. In addition, unlike the previous commissions, the 14th commission did not recommend any discretionary grants. That constituted about 1.5% of the divisible pool earlier. … Considering these factors and to allow the states to have greater discretion in taking expenditure decisions, the commission decided to increase the tax devolution marginally by about three percentage points.”

The 14th Finance Commission was set up by the previous Manmohan Singh government of the United Progressive Alliance. The commission headed by Y.V. Reddy, a former governor of the Reserve Bank of India, operated at a time when the negotiations around implementing the GST system were stuck due to the political climate in the country, for which the Congress leader and then Union minister Jairam Ramesh faulted the “single handed opposition of [Gujarat chief minister] Narendra Modi to [the] GST”. After accepting the suggestions of the commission, the new Central government under Modi started restructuring the flow of grants to states. To save money, the Centre withdrew its support to a set of schemes completely, while for others, it asked the states to contribute up to 50% more, making a dent in their finances.

The Centre used another idea to minimise its loss in the shareable pool of taxes. It steadily increased cess and surcharges to earn revenue. Since they do not fall under the divisible pool of taxes, the Centre kept the entire amount in its kitty without tempering with the recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission.

According to Krishna Byre Gowda, a former representative in the GST Council of the Karnataka government, the contribution of cess and surcharges soared from 9.3% to 15% of the gross tax revenue of the Union government between 2014-15 and 2019-20. PRS Legislative Research found in a study that in the pre-GST period, Karnataka raised 62% of its revenue from its own taxes, a federal right it gave up to be part of the GST regime. “Within two to three years, Karnataka is slipping into a debt trap from being a fiscally responsible state, as it does not get enough funds from the Centre for its expenditure,” says Gowda.

The Centre under Modi has wooed corporates aggressively. Gowda points out the Centre’s decision to give a rebate of Rs 1.45 lakh crore to the corporate sector in taxes—which are part of the divisible pool—in 2019, while making up for the loss by increasing its share of tax on diesel and petrol through basic excise, special additional excise and road/infra cess. Between October 2019 and January 2021, the Centre’s tax on diesel grew from Rs 15.83 per litre to Rs 31.83 per litre, the corresponding figure for petrol rising from Rs 19.98 per litre to Rs 32.98 per litre. The divisible pool of the taxes in this portion of taxes on diesel and petrol, which comes from the basic excise duty (BED), remained static at Rs 4.83 and Rs 2.98 respectively. However, in the Union budget for 2021-22, the Centre revised even the BED to Rs 1.8 on diesel and Rs 1.4 on petrol to accommodate the Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Cess.

Then president Pranab Mukherjee and PM Modi at joint parliamentary session

Who Owns Social Welfare?

The states claim that despite reducing their share of revenue from Central taxes, the Union government has tried to create a pro-Center narrative on social welfare by imposing and exclusively owning Centrally sponsored schemes without consulting them. One such scheme is Ayushman Bharat, touted by the Centre as world’s largest health insurance scheme, which promises to provide a health cover of up to Rs 5 lakh per family for secondary and tertiary care hospitalisation to over 40% of the Indian population. While the states are required to bear 40% of its cost to avail the scheme, it is promoted in the name of the prime minister. In political rallies before state elections, BJP politicians seek votes in the name of this scheme and attribute its success to Prime Minister Modi. Four non-BJP states—Delhi, West Bengal, Telangana and Odisha—have refused to implement the scheme, citing the Centre’s attempt to claim its benefits as theirs while the states are tasked to manage its arduous implementation and bear a substantial cost.

In 2020, in a response to the Centre’s accusations that the West Bengal government was being anti-poor by not implementing Ayushman Bharat, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee replied, “I do not have any problem if the Centre wants to implement the Ayushman Bharat scheme in West Bengal. We have already launched the Swasthya Sathi programme. … Let them bear 100% of the cost for the [Ayushman Bharat] scheme.”

India is paying a heavy price for the Centre-versus-state politics. Overall, the spending on health is still significantly lower than the targets set by the National Health Policy of 2017. In 2018-19, the Centre and states together spent around 1% of the GDP on health, of which 70% was done by states. In comparison, the member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development spend around 7.6% of their GDP on public health. The 15th Finance Commission has asked the Centre to provide more flexibility to states in spending on healthcare.

Covid-19 has put a tremendous strain on state budgets, especially in the health sector. The states argue that the implementation of welfare programmes is largely carried out by them, for which they need more financial autonomy. Shamika Ravi, vice-president of economic policy at the Observer Research Foundation, disagrees. She says, “The argument that the GST regime is a highly centralised system is not sound. At the end of the day, a lot of spending responsibilities are indeed borne by the Centre.” She gives the example of Covid vaccination to support her claim. “Though its implementation ultimately rests with the states, the nature of such problems is that they cannot be left to state capacities. The same applies to markets. Fragmented markets mean big diseconomies. It is not just a taxation issue, but there are also real efficiency gains of a unified market.”

So far, the Centre has tried to dictate terms on how states spend money provided under the Centrally sponsored schemes even if the terms are irrelevant in certain contexts. “The Centrally sponsored schemes have a design problem, because they are based on a one-size-fits-all model. The scheme design does not allow state-level variations. Since [the disbursal of] money is tied to it—which forms a significant part of the revenue of some states—they continue implementing it irrespective of their specific needs. For example, why does Kerala need the Janani Suraksha Yojna? It does well in this field on its own and does not require an overlapping Central scheme,” says Avani Kapur, a fellow at the Centre for Policy Research who studies governments’ welfare policies.

Pronab Sen, a former chief statistician of India who also served as the principal advisor in the erstwhile Planning Commission, argues that the Centre harms development by forcing its terms on the states for Centrally sponsored schemes. “You cannot have the same schemes in two fundamentally different states, like Gujarat and Bihar. Unless the states are allowed to have more say in the development process, we will get suboptimal results,” he says.

Ravi’s answer to such criticism is that not every state has the capacity to raise funds. She says, “Decentralisation in theory sounds nice. And, it is perhaps the right way to go. But, then, what we are basically saying is to each his own, which means that the state which lacks the capacity to collect and manage finances and spend on health, education and organised agriculture is being asked to fend for itself. It is not right in the national spirit to allow for such divergences to emerge at a certain strategic time of India’s growth. That divergence becomes untenable. It is totally unsustainable.”

Future of Fiscal Federalism

There is a clear divide between the BJP and non-BJP states on the issue of fiscal federalism. While the non-BJP states are vocal in pressuring the Centre in giving more to them either through the GST system or the Centrally sponsored schemes, the BJP states are either quiet or tend to settle their demands through internal party apparatus. Blaming the Centre for forcing the states to depend on loans to meet expenditure, Baghel says, “This must have been happening with the BJP-ruled states as well, but they cannot speak out.”

What worked for the Prime Minister when he caused the two economic disruptions seems to be working against him now. In the eighth year of his composite tenure now, he has faced a few electoral and policy reversals and the policy novelty he promised has worn off. The opposition fancies its chances now, especially in state elections, where it feels that an anti-incumbency sentiment has set in against the ruling coalition at the Centre. This feeling, the economic slowdown and the Centre’s inability to pass on the promised GST benefits to the states have made the opposition press home their advantage.

On the other hand, the GST has become a near permanent structure in the Indian economy, and making any amendments to its basic structure will be difficult even if there is a political change in the country.

(With inputs from Ashutosh Sharma & Shamsher Singh)