The ultimate superpower, if you think about it, is the power to influence. Therefore, Dale Carnegie’s 1936 book on cultivating this superpower has a loyal following. The book’s tips include remembering to smile, giving sincere and honest appreciation, and arousing in the other an intense want. So, you don’t need to shoot webs out of wrists; your smile can charm Spidey into doing it. With it, you don’t need to fight crime in a bat costume; you can simply pick the right ‘thank you’ card to send Batman. Or, with it, you don’t need to be rich; you can trigger a compelling want in a rich friend, like a banker, to get him or her to spend for you.

The founder and CMD of Suzlon Energy, Tulsi Tanti, seems to have developed this power to influence. Bank, after bank, after bank, has been giving his company loan, after loan, after loan despite numerous defaults and restructuring attempts. Suzlon has gone through a loan restructuring in 2010, 2012, 2016 and 2020, which is four times over the past decade.

To be fair, green-energy isn’t an easy business. It has an uncertain order pipeline, is money guzzling and involves government policies that are continually evolving. Besides, Tanti entered this business in the nineties, when it looked as fanciful as buying land on the moon.

He started by importing windmills, two of them, when he and his brothers were running the family business of making polyester yarn. Then, textile businesses were incurring huge power bills and therefore found it hard to spend on other things such as innovation. While everyone else was petitioning the government to give them power subsidies, Tanti decided to go off-grid. It must have seemed Quixotic to his peers. Story goes that the brothers were dismantling the mills one day, were intrigued by them and did more research on the wind-power market. In 1995, they set up Suzlon, a portmanteau of ‘soojh-boojh’ (the ability to judge a situation correctly) and ‘loan’.

In an interview given to Time magazine in 2007, Tanti said that he made the global leap after reading in early 2000 that one of his favourite holiday destinations Maldives may go underwater because of global warming. It is an impressive story, and Tanti has an enviable ability to impress. Despite the debt pile increasing and many restructuring deals failing under his watch, he has managed to impress his bankers enough to let him retain control of the company.

“Whichever way the deal is structured, control of the company will remain with me.” That was his brief to Suzlon’s board early last year, when options were being looked at to save his company. At that point, the entity he set up from scratch was staring at a staggering amount of debt and nothing to cling on to but hope. But, Tanti prevailed.

Green turns red

In the early days, he was celebrated as a green warrior. In a little more than a decade, his company had become one of the world’s top three wind-energy companies and Asia’s biggest. In 2005, Suzlon’s public issue was a huge success – the offer price of Rs.510 was no deterrent in a buoyant market and it was oversubscribed 15x. Tanti flew around in his private jet and quite enjoyed the media attention.

Tanti, according to a veteran private equity professional, is a case of a man who thought he was the messiah of the industry. “He is a strange combination of someone who is not a long-term thinker but will speak like a visionary,” says the man who has known the Suzlon founder for many years.

Perhaps, the beginning of Suzlon’s fall can be traced back to 2005, when finance was freely available and Tanti tapped into that supply for the next two years. He bought Belgian-based Hansen for $565 million (then the second largest takeover by an Indian company) and outbid French, state-owned nuclear company Areva to buy German turbine manufacturer REpower. Nothing could stop Suzlon it seemed, not even the blade cracks experienced by some of its US customers. In 2008, the sub-prime crash happened, lender generosity thinned and debtors came calling. That financial year (FY09), Suzlon’s net debt was Rs.118 billion.

Tanti had never been afraid to borrow. In fact, it was a learning he picked up from his time in the textile industry. A Suzlon official, who worked with Tanti, remembers having that discussion with him just after the company had gone public. Tanti said the big insight from textiles was, ‘The first principle of business’ – “kabhi apna paisa mat dalo. You should always look at banks to fund you. Make sure you are in their good books.”

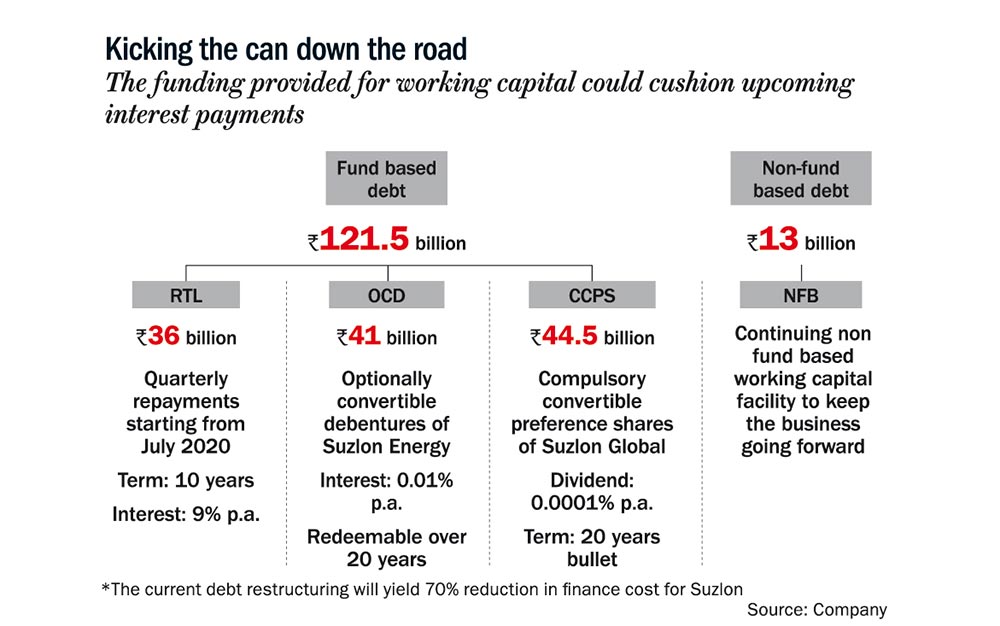

The Suzlon founder seems to have done this pretty well. In a debt restructuring exercise concluded recently, it was decided that the company’s debt of Rs.130 billion would be converted into sustainable and unsustainable loans — the former will be Rs.36 billion and would be paid in 10 years at an interest of 9% per annum. What remains is to be paid over 20 years through optionally convertible debentures and compulsorily convertible preference shares (See: Kicking the can down the road). The resolution plan requires Suzlon promoters to infuse just Rs.3.92 billion.

Effectively, taking into account the time value of money, the banks would be taking 60% haircut. They would also end up with equity in Suzlon at the end of the 20-year period. The consortium of 18 banks was led by SBI which had an individual exposure of Rs.43 billion. The other major lenders were IDBI (Rs.16.7 billion) and Bank of Baroda (Rs.14.58 billion). Outlook Business sent individual queries to prominent lenders in the consortium such as SBI, IDBI, Bank of Baroda, PNB, Bank of India, ICICI Bank and Axis Bank but none responded. A detailed questionnaire sent to Suzlon Energy did not elicit a response either. The company spokesperson confirmed the receipt of the email and said the company's management had nothing more to say on the debt restructuring beyond what was already publicly available.

Amit Tandon finds it hard to understand why this restructuring deal was done, considering the company’s past record with debt restructuring. The founder and managing director of Institutional Investor Advisory Services (IIAS) says, “It could always be that they were convinced by the promoter on the prospects of the company by way of contracts in the pipeline. But a 20-year repayment schedule that has been offered to the company does not support this hypothesis (of improved prospects).”

Suzlon is a case of continuous restructuring, says Shriram Subramanian, founder and managing director of InGovern, a Bengaluru-based corporate governance and research advisory firm. “The restructuring has worked well only for the promoter. Not only has he managed to retain control of the company but has also ensured there is no change in the promoter,” he says. The banks may have a hard-to-break trust in the promoter, but they should have considered the dismal state of wind energy in India.

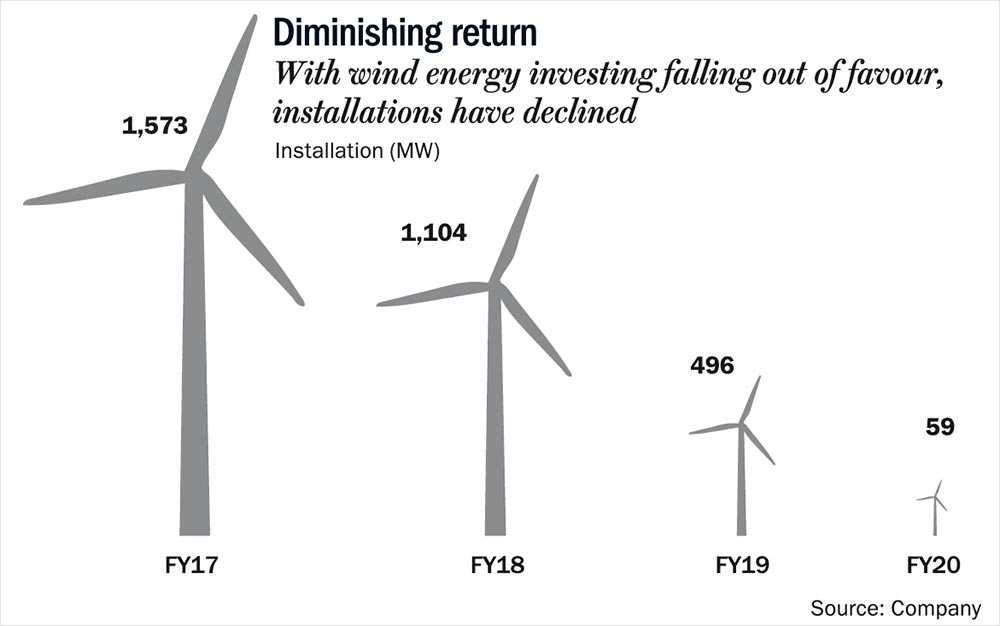

Alternative energy equipment suppliers such as Suzlon are heavily dependent on new installations which have come to a grinding halt. The company itself logged terrible performance in FY20: it installed 59 MW compared to 496 MW in FY19 and on sales of Rs.29.33 billion, it lost Rs.26.92 billion (See: Diminishing return). In FY19, on revenue of Rs.49.78 billion, it lost Rs.15.37 billion. The saviour now and even going forward could be operation and maintenance revenue, which increased to Rs.19.95 billion in FY20 from Rs.19.07 billion in FY19. With FY21 being a washout year, for most capital equipment companies, Suzlon’s short-term prospects look dim.

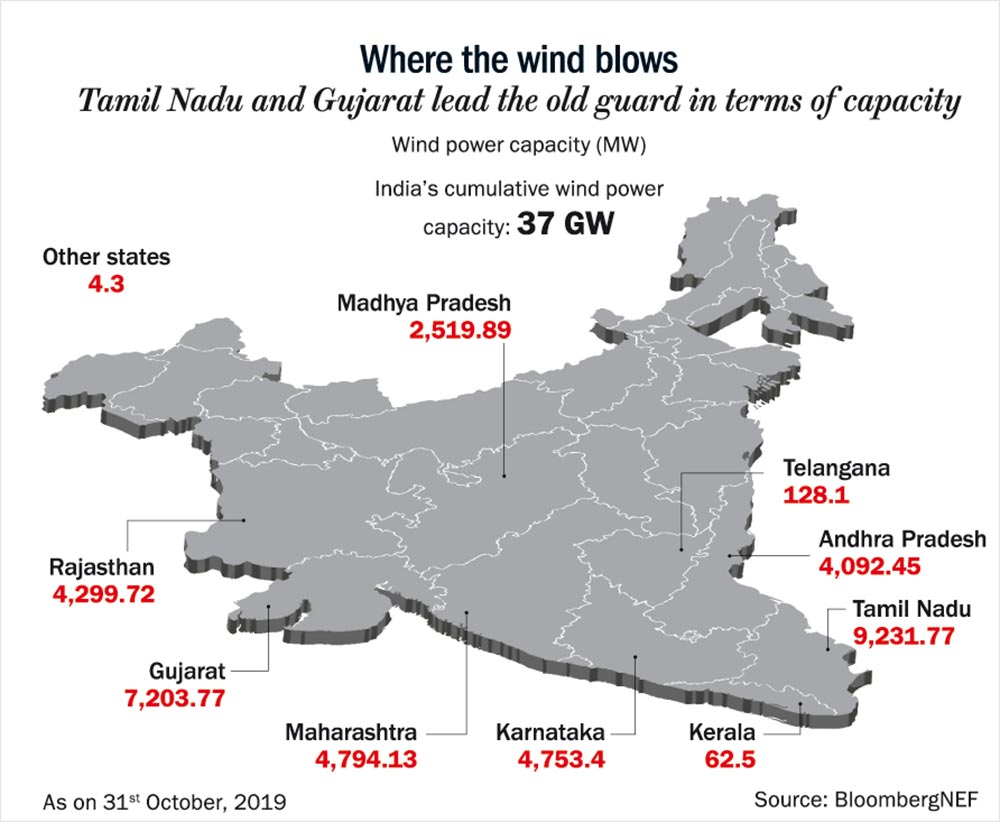

With the economy slowing down, power consumption has anyway been falling drastically. According to Crisil Research, all-India power demand could be lower by 2%, or ~31 billion units this fiscal because industrial and commercial consumers – who pay 50-100% more and cross-subsidise domestic and agricultural consumers – have been the worst hit by the lockdown. In fact, states such as Gujarat, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu saw a fall in industrial power consumption in FY20 compared with FY19. These three states are also the ones with the most installed wind power capacity (See: Where the wind blows).

The big question then is ‘will Suzlon generate enough cash flow to not only run the business but also service the repayment on the Rs.36 billion debt that has been restructured as “viable”?’ At 9%, yearly outgo on that is Rs.3.24 billion. The management has been cushioned for a couple of years at least as the banks have also agreed to finance working capital to the tune of Rs.13 billion. But that does not address the core issue of sustenance in an industry which is in the doldrums. Then there is intensifying competition to contend with.

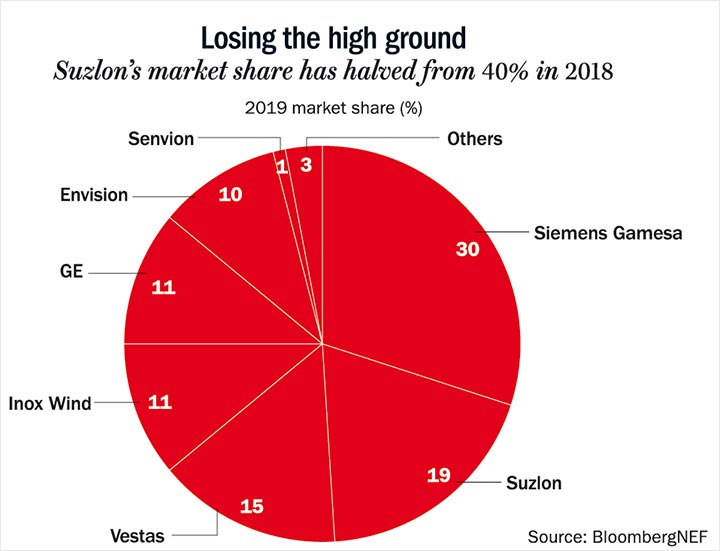

Suzlon has been losing market share to players such as Siemens Gamesa. According to BloombergNEF, in 2019 Siemens Gamesa had 30% market share compared to Suzlon’s 19% (See: Losing the high ground). In 2018, Suzlon was the market leader with 41%. It should test any banker’s patience, but the wind-power company’s bankers are made of sterner stuff, it seems.

Powerful friends

The Suzlon official quoted earlier has no doubt that Tanti had friends in high places, including in banks and governments. “It was fairly well known that access to funding was never an issue. The connections he made both at the state and central levels helped him greatly,” he says. Tanti believed nothing in the industry could change without his knowledge or in some cases would try and push it himself.

The same official recalls a meeting around a decade ago when there was apprehension on how long the benefit of accelerated depreciation (an incentive granted to the owners of new wind assets with the objective of reducing their taxable income; it is done by claiming a higher level of depreciation in the early years that the asset is in operation) could last. “The viability of a project based on a regulatory advantage worried us,” he says. The point was repeatedly discussed at that meeting till Tanti made it clear to the team that “regulation will not change.” According to the official, there was deafening silence in the room. “It was said in a very calm and composed way. He obviously knew more than we did.”

His proximity to bankers is best demonstrated in a meeting to fund the REpower acquisition, a company bigger than Suzlon. It was bought for €1.5 billion and, in true Tanti fashion, the buy was financed largely through debt. Here, a senior member of the lending team was asked to “keep quiet” by Tanti when questions were raised on the long-term prospects of the buyout. “Nobody dared to speak in front of Tanti,” says a banker who recalls the head of the institution not stepping in to support his colleague.

The REpower deal was one that bankers and Suzlon regretted later. Tanti could not make the most of the cash that REpower held as the German banks did not give him a free run. Later renamed Senvion, it was sold for €1 billion to Centrebridge Partners, a private equity group, with the objective of paring down debt. That was in early 2015 and since then Senvion itself has filed for bankruptcy. Its global assets, barring India, were acquired by Siemens Gamesa. A recent media report said the Indian operations could be acquired by Alfanar, a conglomerate based in Saudi Arabia.

The REpower setback hardly made a dent on Tanti’s Teflon-like ambition. The problem being Tanti, who built his empire on debt, never considered it a hindrance, according to a former confidante and now, consultant. “What drives him is ambition and nothing else. You only have to discuss scale with him and he will instantly get carried away,” says the consultant.

According to Harshit Kapadia, associate vice president, Elara Capital, Suzlon’s decision to make big ticket acquisitions such as Hansen and REpower was driven by the ambition to be among the top five wind manufacturers globally. “Besides, the easy availability of finance during 2005-07 and strong global economic growth accentuated that ambition to turn to reality,” he says.

The party ends

When the going was good, Tanti refused to believe that the party would ever end. In many ways, the nasty surprise came from all quarters – weakness in the economy, the changed tariff regime, high working capital, low margins and high interest costs on account of the leveraged buyout of REpower. Kapadia says all this led to Suzon going into the red and net worth turning negative.

The changed tariff regime was perhaps the least expected and one that hit the company hard. In 2017, the shift in feed-in tariff (fixed price contract) to an auction-based system meant lower tariffs. “It dropped sharply from Rs.5-6/kWh to Rs.2.43-3/kWh. That decline in tariff meant an impact on the value chain, be it the developer, wind equipment manufacturer or the logistics companies,” explains Kapadia, who adds that the impact on a wind equipment manufacturer such as Suzlon saw its Ebitda margin dropping by half to 8-9%. Defaults were an eventual outcome for the already leveraged player. Sun Pharma’s Dilip Shanghvi did step in as a white knight in 2015 but failed to stem the bleed (See: When wind met sun).

Last July, the company defaulted on payment on $172 million to the holders of its foreign currency convertible bonds (FCCB). A few months later, all the independent directors including bank nominees (five in all) quit the board of Suzlon. The three independent directors who resigned were Ravi Uppal (earlier with ABB, L&T and Jindal Steel & Power), Vijaya Sampath (a lawyer who was general counsel to Bharti Group) and Venkataraman Subramanian (an energy sector expert who sits on the boards of Adani Enterprises, Sundaram-Clayton among others). The nominee directors were Biju George from IDBI and Pratima Ram from SBI. Ex-board members Outlook Business spoke to admitted that the default was the trigger to step down. “This can prevent an individual from getting on to the boards of other companies for five years. In that sense, we were helpless,” one of them said. While new directors have come on board, IDBI does not have a nominee yet. A few months after the exit of the board members, Suzlon saw money walk away too.

Last September, a deal for paying back about $1.2 billion (Rs.85 billion) in loans seemed nearly done when Vestas Wind Systems called it off. Vestas, which had backed the repayment plan, had been kept waiting for nearly ninety days, while Tanti was convincing the lenders that Vestas was undervaluing Suzlon, according to insiders. A banker involved in the deal says there was a sense of worry but Tanti assured the banks and board that Suzlon was worth more. “That was conveyed to the board as well and then we decided to give it another shot,” he adds.

Earlier, the banker says, Brookfield Asset Management had made an offer to buy a majority stake in Suzlon. But the deal fell through after the wind-turbine maker’s lenders were unhappy about the haircut in the range of 50-60%. Brookfield wanted complete control over Suzlon. Insiders say the asset manager dropped out after Tanti refused to cede operational control. In the banker’s opinion, the lenders’ indecisiveness cost them badly – some of the banks agreed with Tanti on valuation and others were unsure. By October/November last year, it was obvious “there was nothing left in the company with a value of maximum Rs.15 billion. That is when we decided to move ahead with a debt structuring plan,” he explains.

The banker says the priority of the repayment schedule in Brookfield’s offer was statutory payments followed by debt, preferential capital and finally equity. “In that scenario, both the Vestas and Brookfield transactions would have yielded nothing to Tanti. Even the lenders would have had to take a huge haircut,” he says. But, people involved in the restructuring process at Suzlon say Tanti was never keen on closing the deal.

They say he worked only towards a settlement with the bankers. It was almost a sure shot way of ensuring Suzlon remained with him. Tanti’s need to control his business seems to have affected the professional running of his business too. The opinion among many who worked at Suzlon after having worked at other large organizations, is that he is a micromanager and trusts the opinion of a select few – a combination of officials who have worked with him such as Kirti Vagadia, group CFO apart from Tanti’s brothers. “He pays top dollar but is a control freak. The old fashioned lalaji in him is very much there,” points out an ex-Suzlon official.

The management style, he explains, is to seek consensus at work by day and give the impression that he is listening to you. “The same night, the brothers will sit together and decide the course of action before it is presented to the rest of the team. The professionalism story is there but only for public consumption.”

Fiduciary neglect

Tanti might be accustomed to doing things his way but why did the lenders not approach the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) for recovery? What came to Tanti’s rescue was the inter-creditor agreement approved by RBI on June 7 last year. The new directive gave banks the discretion to implement a resolution plan within six months, failing which the stressed account would be dealt at NCLT.

A banker to Suzlon defends their decision of not approaching the tribunal. He says Suzlon’s business model is akin to an EPC player and the new buyer will need to build the business from scratch. “The company needs to procure orders to be in business. Companies that have found a buyer after going to NCLT are those with a strong asset base. The larger consensus was that approaching the tribunal would have yielded only 15% of the value, besides being time-consuming,” he adds.

Clearly, this defense does not hold much water because it conveniently ignores the nearly Rs.20 billion in O&M revenue that the company had in FY20. Suzlon itself plays it up in its investor presentation as “Stable service revenue insulated from business cycles”. The banker’s explanation would have made sense if that O&M revenue was cyclical or faced potential decline going forward. It sounds even more incredulous as the SBI-led consortium eventually took 60% haircut, the higher end for which Brookfield was negotiating.

InGovern’s Subramanian says the banks should have been more aggressive with the recovery process. “Tanti has got a sweetheart of a deal. Banks need to say ‘no’, push the company to IBC and force a change in the management,” he explains. Given that the company has already gone through restructuring earlier, Tandon says that another restructuring just delays dealing with the problem. “The right thing to do was take the company to NCLT,” he says. If approaching the tribunal looked like a wasted effort, lenders did have other options, other than restructuring.

These options were deliberated on, says the banker to Suzlon quoted earlier. But none of them seemed promising. If they invoked the personal guarantee and pledged holdings of Tanti or if they had auctioned assets, it would have been a time-consuming affair with no surety on how much would come out of it.

Whatever the justification, according to Subramanian, perennial debt restructuring simply sends a negative message. Investors and shareholders may find it difficult to trust the company again. “Ideally, the bankers should have insisted on a change in management before anything else. It appears as if the promoters have the bankers on their side,” he says. Tandon says the lackluster movement in the stock price post the latest restructuring is an indication that the market does not believe the future will be any different.

A week after Suzlon’s debt restructuring announcement, the company announced its Q4FY20 numbers where it lost Rs 8.34 billion. The bigger news was the resignation of its group CEO, JP Chalasani, a veteran of the power sector. Prior to joining Suzlon in April 2016, he had stints at Reliance Power, Punj Lloyd and NTPC. Chalasani was one of the key people involved in the completion of the debt restructuring. That complicates issues since there is no clarity on who will run the company on an operational basis. There is almost no coverage on the Suzlon stock and concerns remain. InGovern’s Subramanian points to the lack of “noteworthy shareholding in Suzlon.”

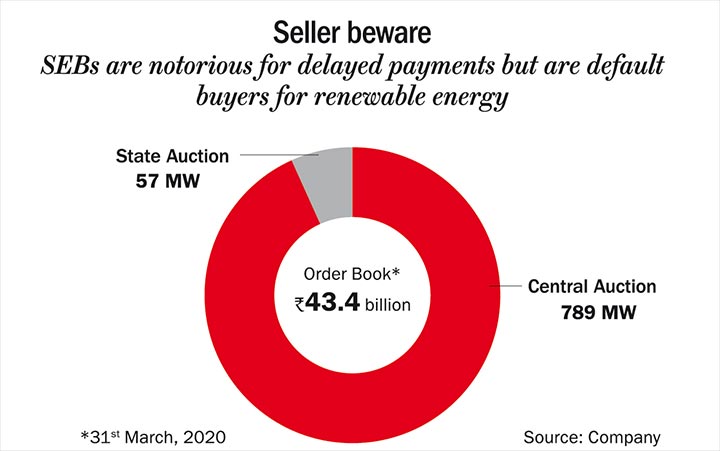

The other worrying part is that bulk of Suzlon’s order book flows through central and state auctions (See: Seller beware). Given the stretched fisc and low tax collections, it is questionable if the government will drop everything and divert money to clear receivables of the wind power sector. The finances of state governments are nothing to speak about either, more so as the Centre has still not released their share of GST collections for FY20. In such a background, it would be very optimistic to assume that Suzlon’s existing order book will see either smooth execution or prompt payments by SEBs.

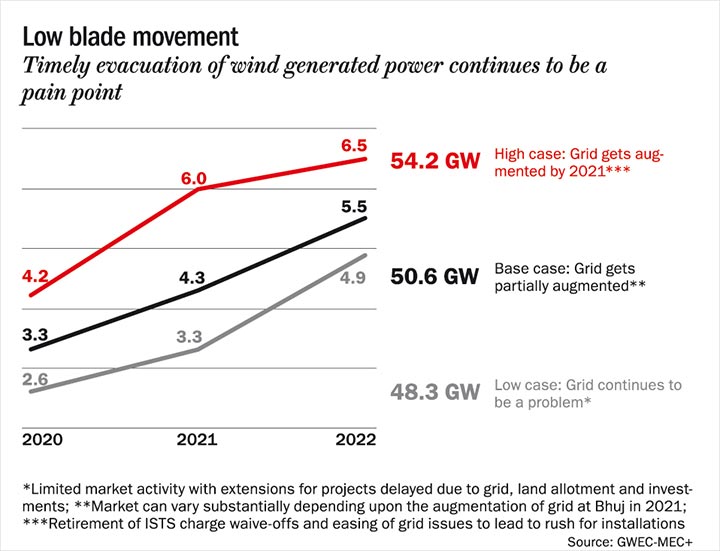

As it is, for the overall wind-power industry, capacity addition has slowed down. Only 2.4 GW was added in 2019, compared to 2.3 GW in 2018 and 4.1 GW in 2017, according to a May 2020 report by Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) and MEC Intelligence. In 2020, the target addition was 2.6 GW, which seems hard to achieve given the washout post COVID-19. The GWEC report says that India’s wind energy capacity can only realistically reach 50 GW by 2022 from 37.5 GW in 2019 (See: Low blade movement). That is 16% lower than the 60 GW target set by the government. Ben Backwell, CEO, GWEC had then remarked, “Targets alone are simply not enough. Setting realistic prices, a faster build out of grid infrastructure, ensuring market liquidity and streamlining land allocation and site development will be crucial to revive auction appetite and accelerate execution of India’s pipeline of wind energy projects”.

Even GWEC’s 2022 projection of 50 GW seems optimistic as Crisil has projected 49 GW by 2024. In its September 2019 report, the rating agency had pointed out, “As much as 26% of the 64 GW of projects auctioned by the Centre and the states have received no or lukewarm bids, while another 31% are facing delays in allocation after being tendered. Thus, despite the increase in tendering volume, not only has allocation of projects slowed down, but both under-subscriptions and cancellations of awarded tenders have also increased.” Shortly after Crisil’s report was released, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy termed the report as “ill founded, factually incorrect and lacking credibility.”

Even as the orders are slowing down and interest in wind-power projects is weakening due to falling return on investment, what if some of the existing orders get cancelled on the grounds that they are no longer viable? Suzlon itself mentioned in its Q3FY20 investor presentation that “632 MW has been considered as cancelled from the order book due to teething troubles of land, power evacuation and other constraints.”

The GWEC report, too, had pointed out, “Grid and land availability, off-taker risks, onerous tender conditions and low tariff caps have led to the last three central wind tenders and all state wind tenders to be unsubscribed, retendered or even cancelled, while 80% of awarded projects have been delayed by 6-12 months.”

In its worst form for Suzlon, the story of renewable energy in India could one be of solar trumping wind. Solar has made great strides in the face of falling technology cost, accommodative policy and the fact that wind power installations are largely topography dependent unlike solar. Hence, for wind OEMs, you cannot ignore the other possible scenario.

When a sector stagnates for long, consolidation is the eventual outcome. Tanti though is loath to give up control and even if he moves in that direction, it might just be with a wind/solar player where he gets to call the shots. Wind-solar hybrids are being bandied about as the next big thing and the removal of tariff caps for future auctions could just be the icing on the cake.

Will Tanti have another epiphany, about working collaboratively?