When the top brass at the Thapar Group met in early 2007, it was to give the diversified group a new identity. That seemed a bit odd since companies such as Crompton Greaves (CG) and Ballarpur Industries (bilt) were well-known entities. Understandably, there was an apprehension that doing away with the parent brand would take away the strength of its constituents.

But promoter Gautam Thapar had his own rationale and he has always had his way. It had been nearly a decade since the holding company, KCTB or Karam Chand Thapar and Bros, had been split within the family. Now, the 46-year-old was keen on carving out his own identity — one that did not come with the baggage of the past. It was his way of telling the world that he had emerged from the shadows of the family and most importantly that of his uncle, Lalit Mohan Thapar.

By November that year, the Avantha group was born. The name denoted a combination of — avance standing for advance in French and sthapna in Sanskrit meaning establishment.

The story doing the rounds was that tha stood for the first three letters of Thapar, though nothing could be farther from the truth. It was no more than a coincidence and like most good stories, has sustained over time. Avantha was meant to express “growth with stability.”

The suave and articulate Gautam had already made his mark as someone with the ability to turn around troubled businesses. At the time of rebranding, he had led BILT’s acquisition of Sabah Forest Industries, Malaysia’s largest pulp-and-paper company for $261 million. Brimming with confidence, which could be mistaken for audacity, Gautam had become the promoter of a $3 billion group, with presence across paper, power transmission, food processing and chemicals.

A decade later, the glory of the past seems remarkably distant. Cut to the present and you have 58-year-old Gautam, who is in the midst of his biggest crisis ever. Ousted by the board of his flagship, CG Power and Industrial Solutions, following a series of financial irregularities, he now has his back to the wall. It has been a remarkable fall from grace.

Wonder kid

In Delhi circles, Gautam, or GT as he is called, is known to be low profile with a small circle of friends. Born into wealth, he went to Doon School in Dehradun and distinguished himself in sports, even captaining the Hyderabad House. He then moved to St Stephen’s College in Delhi, to do his graduation in 1979, but dropped out after the first year.

The Thapars had no reason to strive and sweat; their business group founded in 1929 by the late Karam Chand Thapar was formidable. The patriarch started as a coal trader before he ventured into sugar and paper, and even banking by buying Oriental Bank of Commerce. Lalit Mohan Thapar (LMT), to whom the reins were handed over in the second generation, said in an NDTV interview that his father grew his empire by buying out businesses the British could no longer afford to run, during WWII.

While his grandfather seemed driven, Gautam (by his own admission) had been laid-back before joining the family business. The attitude carried a shade of the disinterest his father, Brij Mohan, showed in heading KCTB when it was offered to him and he passed it on to LMT. After his short stint at St Stephen’s, Gautam left for the Pratt Institute in New York in 1980 to pursue chemical engineering; he had always been fond of the US. He came back in 1984 and, for a year, he seemed to be drifting aimlessly and even moping. That’s when he found his “greatest mentor”, in GT’s own words, in BM Bakshi, who was also his father’s close friend and VP for the Thapar Group.

Gautam’s first assignment with KCTB was a short stint in one of BILT’s big manufacturing plants in Yamunanagar, near Delhi, in 1985. Then he worked across divisions in the Thapar Group and soon was unhappy with the way things were being run. In an interview with Bloomberg UTV, in 2011, he said that his motivation to take on a leadership role came from wanting to rescue a legacy from being wasted. It was a harsh judgement but he said it with such conviction that won over his uncle LMT, who had till then been grooming Vikram Thapar (son of Karam Chand’s eldest son Inder Mohan) for the mantle. Later, LMT even bequeathed Gautam his voting rights and shares, and BILT.

It was warmth that had taken time to build. The two Thapars had not got along well in the beginning; in fact, in the Bloomberg UTV interview, Gautam did not deny that they had not been on talking terms once. There is a story from journalist Mini Menon’s Riding the Wave that reiterates this. During the last year of college, Gautam decided to get a job in the US. He went to LMT’s friend for help, who asked Gautam to check with his uncle. LMT was livid when Gautam spoke to him. A heated argument followed and the senior Thapar eventually said, “You will end up being a waiter in the US!’ Gautam responded: “At least, I will be a happy one! After that, uncle and nephew did not speak for years. The thaw did melt eventually, especially after the nephew turned around a troubled group company, Andhra Pradesh Rayons.

At this manufacturer of rayon pulp, one of the earliest crises Gautam had to handle was bad blood with Grasim, which contributed half its revenue. Quality standards had caused a falling out between the two. After many meetings with the Grasim top brass, Gautam assured them of his commitment and the deal with the largest customer was back on track.

The next assignment was to turn around BILT, which had a host of business such as chemicals, IT, glass, in addition to, of course, paper. The strategy was to make it just a paper company and that was at a time when Indonesia’s Sinar Mas was in the midst of setting up a massive plant near Pune. That was in 1997. For Gautam, moving the non-core businesses to another company or divesting them was as important as making BILT ready for some serious competition.

The other family members were worried about divesting, anxious about negative market sentiment or what LMT who had started that vertical would feel. But Gautam was surprised that their opposition to his decision was sentimental and lacked financial reasoning. He told them that as CEO of the company, he had been tasked with making BILT competitive and he would do that as he knew best. If LMT, who was the chairman, had a problem with his methods, then he should appoint another CEO. Gautam did not speak from conceit, but was simply stating facts as he saw it.

He sold the residual stakes in the glass business, the BILT-DuPont joint venture to make nylon, The Pioneer newspaper, and the chemical business was spun off to create Solaris Chemicals. These measures, despite apprehensions of the other family members, helped revive BILT, which raised money in 2001 and even bought over an almost brand new plant from Sinar Mas.

Close circle

In many ways, Gautam stands out from the Delhi crowd. He spends most of his time living in Dubai and London with his German wife, Stephanie. Those who have met him swear by his sartorial sense and the GT initials on his cufflinks. A key interest is golf and he is on the board of Professional Golf Tour of India. For his fiftieth birthday, he threw a party in Phuket which had live music by the likes of Donna Summers and The Pointer Sisters. “GT represents the old aristocracy of Delhi and Punjab with a bit of a swagger,” says a former group official.

A father of four, the intensely private industrialist is not known to easily open his home to guests, with trust being restricted to a handful of folks such as Sanjay Labroo, CEO of Asahi India Glass, also his junior from Doon School and BILT board member. Another friend is fashion designer Tarun Tahiliani, whose son Jahan is on the board of Avantha Technologies. Within the group, his lieutenant is B Hariharan, director and CFO of the group, who has been around for three decades. Bankers who have known him for years say Gautam will heed the opinion only of his top brass, which is no more than three to four executives including Hariharan and the former head of CG, KN Neelkant. Therefore, there has been high attrition in the mid and senior levels in the company, says one banker. “Gautam will easily ignore your opinion and can be scathing even when things are not going in his favour,” he adds.

He trusts his lieutenants to run the show but nothing of importance has ever missed his attention. Executives close to the current crisis at CG Power (it brings in 60% of Avantha’s revenue) are certain that there is no way Gautam could have not have known what had transpired over the last couple of years in the company.

The CG board began to feel the tremors this March, when an operations committee was formed for seeking refinancing of certain facilities. Narayan Seshadri, founder, Tranzmute Capital, who is also on the board of CG Power, headed the operating committee. Two separate incidents that same week, forced the board to swing into action (See: Boardroom battle). First, a cheque issued for Rs.1 billion bounced, and the other was receiving a note from a lender that CG Power had defaulted on an interest payment. In both cases, the transaction was not visible on the liability side of the company’s balance sheet. The guarantees were given by CG Power and the board had no knowledge of this.

Hence, the board brought in an independent law firm Vaish Associates, who in turn reached out to Deloitte, to conduct a probe. Sources say that when the investigation began, there was resistance from the top management, especially Gautam. This reluctance on his part was interpreted as an indication that something was being concealed.

According to the report, prima facie evidence points to money having been diverted to “certain companies in which the promoter is a major shareholder.” The law firm’s report had been handed over to an internal committee and a copy was given to Gautam. The committee, after analysing its findings, presented their observations to the board. “While it has not been proven yet, none of what is in the report can be ignored. It has been established that a fraud did take place and there was no option for the board but to inform the Ministry of Corporate Affairs,” said one company executive. Those close to the development say any information that is market sensitive needs to be communicated and not doing so is viewed as a criminal offence. “This was a fraud under his leadership and a forensic investigation was the next step,” says an executive close to the development. Sources say about Rs.40 billion was “concealed” and the “issue was never addressed”.

A few years ago, in 2011, a red flag was raised on corporate governance at Crompton Greaves. It was to do with the purchase of a private jet, when the company was not posting good numbers. Reportedly, institutional investors pressurised the management to sell the aircraft. This time, the backlash carries a deeper sting. A source at the company says that this definitely marks the first instance in Indian corporate history of independent directors taking the initiative on a host of issues, including the ousting of a chairman. “A lot of people would say independent directors are toothless and have repeatedly maligned them for not being ‘independent’. In most cases, the independent directors would have let it pass, that is what makes this case so different,” says the source.

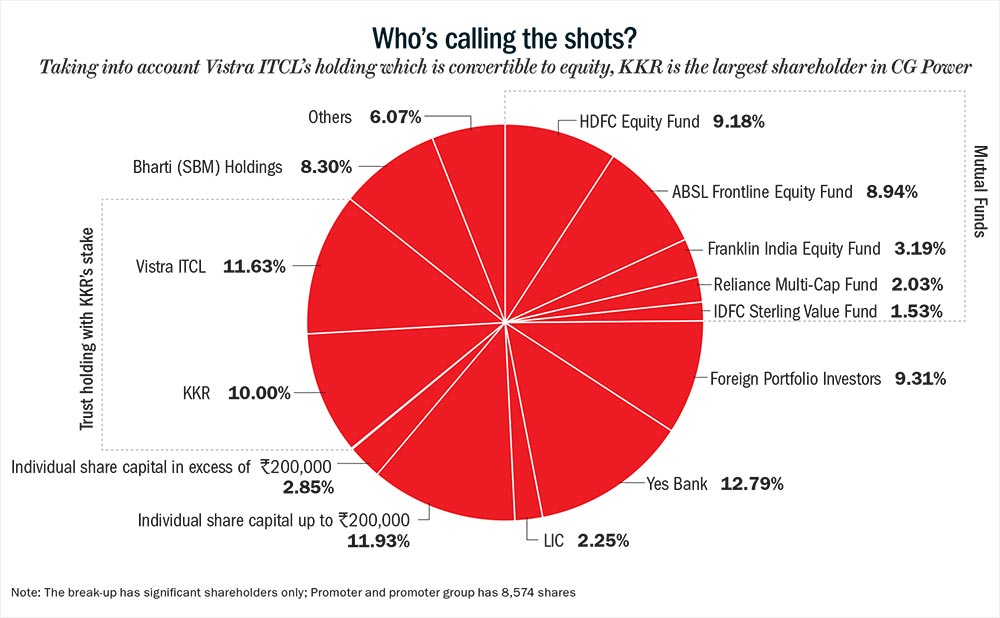

When the report was tabled at a board meeting, an emotional Gautam is said to have apologised to the members, “for putting them through this embarrassment”. At the same meeting, he also is said to have defiantly told them that they were fully aware of what was going on and were, therefore, equally responsible. Left with no option, the board intimated him late in the evening of August 28 that he had to go. Not surprisingly, he refused and the board spent a good part of that night drafting a communiqué that went out to the stock exchanges at 11 AM the following morning. It mentioned that Gautam was being ousted. What made taking this action easy was that most of the promoter holding was now pledged with financial institutions, Yes Bank being the largest (See: Who’s calling the shots?). This does beg the question whether the board was acting on someone else’s behest. The other investor with high stakes was KKR which had lent to Avantha Group. Earlier in March, KKR had invoked the pledge and in mid-September, it converted its exposure in CG Power, earlier held in a trust, to a direct stake of around 10%.

Amit Tandon, managing director, IIAS, says it is difficult to say what might have happened in the boardroom. “But the flow of funds between the company and the promoter-controlled entities, whether at the behest of the board, as Gautam Thapar has alleged, or without the board’s knowledge could not have taken place without explicit directions,” he says.

Responding to queries from Outlook Business, KKR, in a statement, said, “We have been a lender to Avantha Holdings and were not a shareholder of CG Power until we enforced our share pledge (on September 16, 2019), as a result of defaults by Avantha Holdings. As a result of our enforcement, we now own just under 10% equity stake in CG Power. As a shareholder, it is in our interest to engage constructively with the company, both through its board and shareholders, in order to preserve and enhance the value of the company.” Tranzmute’s Seshadri and KKR India head Sanjay Nayar are directors in Epimoney and EPI Venture Partners. About Seshadri’s involvement at CG Power, the earlier mentioned KKR statement clarifies, “The appointment of Narayan Seshadri as an independent director, predates our share pledge enforcement and in any case it is entirely within the board’s power to manage the affairs of the company in accordance with its charter. That said, we would like to state that the partnership between KKR Capital Markets India and Tranzmute was established and announced in 2018.” In his defence, Gautam has sent the board a legal notice challenging his removal and has accused them of being selective in its disclosures to the regulators. He has also asked for minutes of meetings the board members held with senior management, which led to their conclusion that there was misrepresentation of funds.

Shriram Subramaniam, founder of corporate governance advisory firm, InGovern, says Gautam was in an executive role and cannot feign ignorance. “Many of the transactions involve related parties and it should be noted that each of them were large-size in nature, not in the usual course of business,” he explains. In his opinion, CG Power’s management may not have kept all the directors informed. “It is possible that they would have taken enabling approvals from the board without disclosing the parties involved in the specific transactions. It is the duty of the management to keep the independent directors informed, when it comes to related-party transactions,” explains Subramaniam. A statement put out by the company on August 20 said that “it had understated liabilities and advances made to related and unrelated parties, among other financial irregularities”. Liabilities were understated by Rs.26.61 billion and advances (to related and unrelated parties) were understated by Rs.47.96 billion.

Ideally, the auditors should have caught this lapse, except they seem to have been rotated a few times and for no apparent reason. After the mandatory change of auditors, incumbent Sharp & Tannan made way for Chaturvedi & Shah on September 22, 2017. They resigned from the position on April 27, 2018, without citing any reason. The founder DN Chaturvedi is a veteran chartered accountant, whose clientele has included names such as RIL, ADAG and Jet Airways. The current auditor is KK Mankeshwar & Co, a Nagpur-based firm – they came in as joint statutory auditor along with SRBC on May 29, 2018. A source close to the developments in CG Power confides, “It was obvious Chaturvedi & Shah, the auditors who resigned, realised something was not right. Gautam and his team then appointed Mankeshwar’s firm, since it was close to them… that was the reason for bringing them in.” Chaturvedi & Shah was also the auditor for DHFL. Last month, they resigned and it was kk Mankeshwar, again, who replaced them. The insinuation is that the chairman brought in someone amenable. Outlook Business reached out to Gautam’s communications team for a response but they declined to comment.

Falling apart

Things started going awry for Gautam in 2006, after the Sabah Forest deal which was meant to boost the paper business. He had said, “Sabah was insurance for BILT’s future growth” by providing easy access to pulp and cheaper production in Malaysia. The asset came with not just pulp and a paper mill but a jetty, power plant and a steam generation facility. The plan was simple — source pulp from the Southeast Asian country and make paper here.

As luck would have it, global supply of paper took off on the back of high levels of liquidity, leading to capacities being increased. Prices crashed three to four years after the buy, and moving the pulp was not a viable proposition anymore. Today, BILT is saddled with a debt of over Rs.45 billion. When once Gautam had grown Avantha through acquisitions, he has spent the last few years getting rid of most of them.

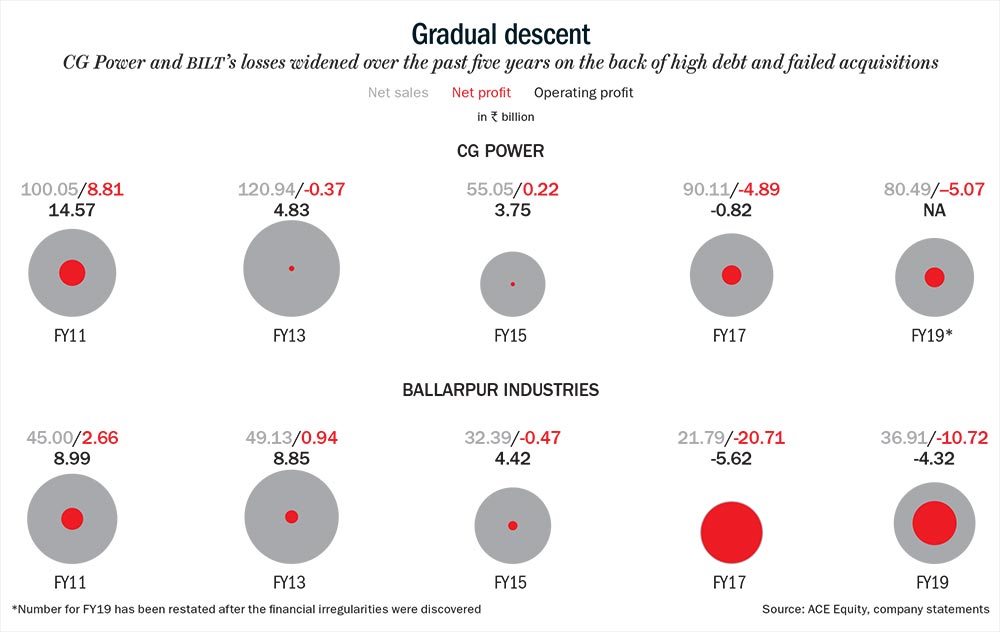

Meanwhile, BILT has just been hurtling from one crisis to another. On revenue of Rs.36.91 billion for FY19, it made a loss of Rs.10.72 billion, with the company in the red since 2015 (See: Gradual descent). Its stock crashed from a high of Rs.125 in June 2006 to the current Rs.0.60 with a market capitalisation of Rs.710 million – 99.96% of the promoters holding has been pledged. A subsidiary, BILT Graphic was on RBI’s list of defaulters after racking up loans worth Rs.60 billion to banks, and has been referred for resolution under the bankruptcy law.

While the buyout of Sabah was a stumbling block, it was the power generation foray that spelt doom for Gautam. The plan to list Avantha Power and Infrastructure was announced in late 2009. This entity would host two thermal power projects — Korba in Chattisgarh and Jhabua in Madhya Pradesh. In an interview with ET NOW, he had said that he saw Avantha Power as one of the bigger companies that would drive the group’s growth and double its revenue. His enthusiasm was not returned by the market and that IPO never took off. Plans to revive the group company in 2012 did not materialise either.

The foray into power coincided with a host of other players such as GVK, GMR, etc also taking a fancy to the sector. Everyone had noticed that there was an attempt to boost power supply by the government and more coal blocks were being opened up to the private sector. Since Avantha, through Crompton Greaves, was already in the business of manufacturing power transmission equipment, power generation seemed like a natural extension. Once the coal allocation scam broke in 2012, those setting up thermal power projects feared the worst and, two years later, the Supreme Court quashed the allocation of 214 coal blocks. Money had already been raised in some form – equity or debt or both – and there was no project to speak of.

Most people who know Gautam say post the power-foray-crisis, he was a changed leader. His management style was more “hands-on” now compared to a time when he was, in many ways, far removed from what was going on. “The setback in his power projects rattled him and he knew it was the beginning of a long road ahead,” says one such person. It was time to swing back into action.

In the exuberance of the power boom, the company seemed to have made acquisitions in a hurry. A private equity veteran, who took a look at the Korba project around six years ago, recalls being shocked that there was no siding in place (to move coal to the plant). “It was obvious that more time would be required to transport the coal, which also meant higher costs. There was no power purchase agreement (PPA) either with the state electricity boards,” he narrates. Revenue quite clearly, according to him, was inadequate to service interest costs and a capital crunch lay ahead.

Isaac George, CFO, GVK Group, agrees that cost of transporting coal goes up nearly 10x without the siding – from Rs.150/tonne to Rs.1,200/tonne. But not having a PPA was not unique to Avantha Power. Shockingly, this has been true of 90% of the private players in India. “The approach is to set up a plant and then look for ways to monetise it,” he says.

After much negotiation, Adani Power, this April, issued a letter of intent to acquire Korba West Power Company, which is in the midst of an insolvency resolution process. The Jhabua plant is also on the block with Avantha Power doing all it can to escape insolvency proceedings.

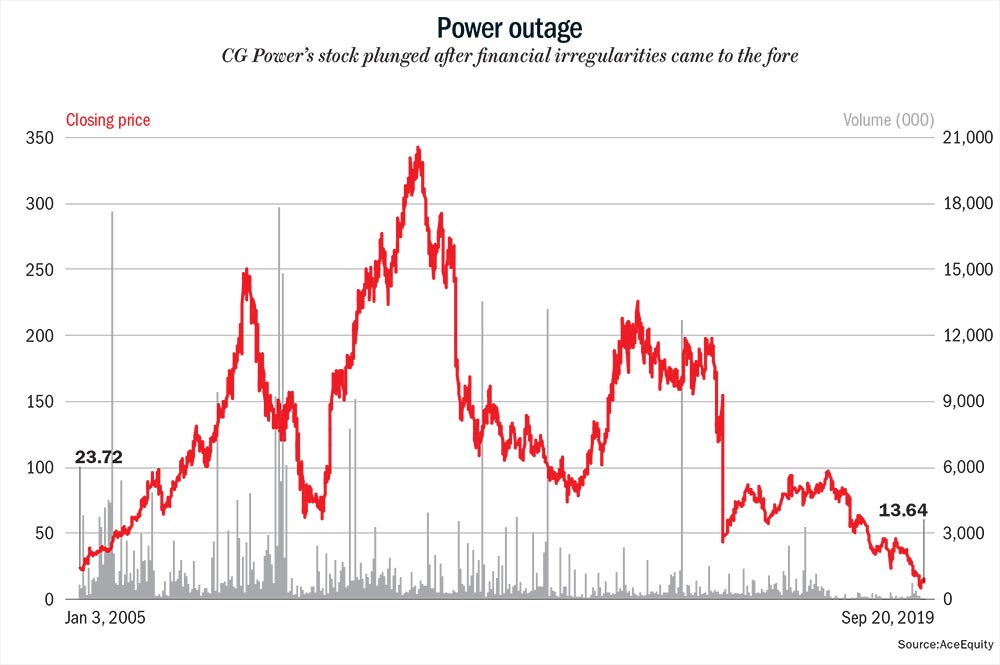

Finally, to get some financial breathing space, the group put Crompton Greaves on the block. Though Gautam has often claimed to be non-sentimental while making business decisions, this would have hurt — it was a company he had turned around. CG had been in his family since 1947, when Crompton and Company that provided electrical services throughout the British Empire changed hands; it found itself in the red in 2000, for the first time. Gautam stepped in and, in mere three years, reversed its fortune by reducing the workforce and exiting non-core businesses such as telecommunications (it had a small stake in Skycell which operated in the Chennai cellular circle). Gautam figured that there would be enough takers for this business. But, unexpectedly, the many acquisitions it made during his watch over 2005-2012 backfired (See: Power outage).

Initial symptoms that all was not well was evident in FY12 when the company’s net profit crashed by almost 60%. Sameer Kalra, founder, Target Investing, says CG’s acquisitions were in sectors with high working capital requirements. “All the major acquisitions were done before the global financial crisis, which meant they were bought at the highest revenue and profitability level,” he says. The overseas business had become the biggest drag. Competition was cutting prices and customers were not taking delivery. Smaller businesses such as the one in Canada were quickly sold, though the larger piece that was in parts of the US, Indonesia and slowdown facing Europe continue to struggle.

Realising this, in the middle of 2014, CG changed tack and decided to sell only its consumer-appliances business – this had fans, air coolers and lighting systems apart from other electrical appliances. It took a full year for this to conclude and when private equity biggies, Temasek and Advent International finally agreed to acquire the entire 34% stake that the promoters held for Rs.20 billion, it was at least 50% lesser than what Gautam had expected. In 2016, CEO of CG, Laurent Demortier, was let go. Company sources say that Demortier (who succeeded Sudhir Trehan) was partly to blame as he did not hold back on spends by opening large offices in places where the company had made an acquisition or just staying in plush hotels. Neelkant, who was Avantha Power’s CEO, replaced him and the Crompton Greaves became CG Power a year later.

True to his word, of placing financial prudence before sentiment, Gautam had even put the iconic Crompton Greaves building in Worli on sale. A deal was inked with Oberoi Realty, in August 2015 and this 150,000 square property was to be sold for approximately Rs.2 billion. Officials in the real estate industry say that the dealbreaker was a last-minute shocker in the form of a liability to the extent of Rs.300-400 million, which had to be paid to the BMC. Oberoi was not willing to foot that and Crompton did not relent.

The group’s last citadel – CG Power – has been in the red, since 2016, according to Harshit Kapadia, associate VP, Elara Securities. He says, “Its inorganic strategy was to gain access to technology in transmission and distribution industry and enter into international markets. But, weak global environment, rising competition from Chinese and South Korean players, higher material costs, lowering of product prices to secure orders in global markets, especially in power transformer markets and order delays resulted in losses, along with inventory and provision write-offs.” According to Target Investing’s Kalra, “The separation of the consumer appliances portfolio has only left more stressed businesses in CG Power. The damage is significant and it will be difficult for the company to receive any new orders in India until control is given to a solid engineering group.”

Gross consolidated debt stands at Rs.28 billion and debt-to-equity stands at 1.2x in FY19. Its standalone profit stood at Rs.1.2 billion, while the consolidated loss was at Rs.3.2 billion in the same fiscal. According to Kapadia, to repay its debt, the company needs to generate a cash flow of Rs.7-8 billion per year, over the next two years. But the current crisis makes that task very tough.

Kapadia says, “It will be a long drawn process starting with outcome of forensic audit, identifying the promoter, appointment of new board of directors, new chairman and CEO. It would certainly be difficult for them to get new orders because they need to be supported by bank guarantees, good track record and execution capability, which has been hampered severely in the market.” Tandon, on the other hand, sees a parallel between Fortis and CG Power. He explains, “Fortis provides a playbook – the difference being that it may not really be necessary to bring in strategic investors immediately. But it depends entirely on the bankers comfort with the restated financials and their willingness to meet working capital requirements.”

Everyone for the moment has sidelined Gautam Thapar, but he is known to be a fighter. The stark difference this time is that he is now the proverbial outsider battling allegation of fraud. In an interview with ET NOW, Gautam had described how he had started golfing with a rusty 5 iron. When the anchor quipped that he has since mastered the game, as well as his business despite having been given an enterprise that was falling apart, he had said that perhaps sums up his life. “There goes Gautam Thapar, he is good at rusty businesses,” was his repartee. In 2011, he exuded a quiet confidence. Will he get another shot at redemption?