Navin Kumar, a 35-year-old Uber driver in Delhi, can’t hide his frustration. It is apparent in his voice as he speaks. “I was better off without owning a car,” he sighs. Two years ago, Kumar was employed as a driver with a corporate house, a job that fetched him Rs.17,000 a month doing the rounds of the city office and the airport.

That changed when Kumar was bamboozled by the Uber-Ola marketing spiel that promised drivers joining their network more than just a better life. There were tales of how the children of drivers were going to English medium schools, and how even postgraduates were hitting the road to earn that extra buck. These tales spurred many like Kumar to cobble enough money, either by selling jewellery or some asset, to make that downpayment and register a brand new vehicle with Ola and Uber. Kumar, too, availed of a loan to buy a Maruti Swift Dzire. Initially, the going was good. Till mid-2016, he made an impressive Rs.70-80K a month. But the honeymoon period did not last for long. Today, Kumar’s earnings are down to Rs.15,000-Rs.18,000 a month. “I need to drive additional hours for that,” he complains. What Kumar claims to take home is hardly enough to cover his expenses, which includes a Rs.13,000 monthly loan instalment. Fuel, maintenance, and other costs make ‘Uberpreneurship’ an unviable pursuit for him.

This explains why in February, a distraught Kumar participated in a strike with fellow Uber drivers facing similar woes. Their demands included revival of higher incentives, discontinuation of commuter pooling, and a base fare hike. Having earlier doled out generous payouts to attract drivers, both Ola and Uber have gradually lowered their incentive structures. The reason? The number of drivers plying its vehicles substantially increased, resulting in fewer bookings and lower incentives.

Avnish Bajaj, managing director of Matrix Partners India, an early investor in Ola Cabs, explains, “What has happened is that drivers have upgraded to a more expensive lifestyle. Let’s say they have bought two-three cars or bought a property. That’s what the challenge is — not that the model is unsustainable for them.”

Uber and Ola did not respond to queries sent by Outlook Business.

Amit Jain, Uber’s president for South Asia and India, through a blog on Uber’s website has admitted that some drivers are earning less than three years ago. Jain, however, mentions that the earnings are still attractive for a majority of drivers even after the reduction in incentives and taking into account the driver’s costs.

In Delhi, disillusioned drivers of Ola and Uber have formed a union known as Chaalak Shakti. Founder Rakesh Agarwal, sitting in Chaalak’s Patparganj office, feels the turn of events was a ticking time bomb as the artificial incentives were not sustainable. Agarwal is also known to have mobilised Delhi’s autorickshawalas for the Aam Aadmi Party in the past. His previous attempts in the space of aggregating cabs under Magic Sewa didn’t succeed, but he now has a fresh idea — the taxi union’s own application, the Sewa app. “We will roll out the app by the end of April. There are many distressed drivers who have joined us. Many more will come on board once the product gains acceptance,” he hopes. There will be no surge pricing, no service tax (as the income goes directly to the individual), and no commission to be paid to the union.

A similar initiative has been announced in Bengaluru. However, here, the issue has acquired a political tone. JD(S) leader HD Kumaraswamy has announced a Rs.50 crore investment over the next two years into his venture HDK Cabs that is set to roll out in a month to rival Ola and Uber.

Chennai has its own start-up named Utoo. Floated by Aircel founder C Sivasankaran, the taxi aggregator raised eyebrows back in August 2016 when its founder promised home ownership as an incentive for high performing drivers. The initial euphoria then gave way for the real news peg: Utoo would simply provide funding for those drivers interested in buying affordable housing projects outside Chennai. Having also entered Hyderabad and Bengaluru in the past four months, Utoo has plans to enter other key markets over time. Even as other players are trying their luck as cab aggregators, the market dynamics are undergoing some serious change.

Fare play

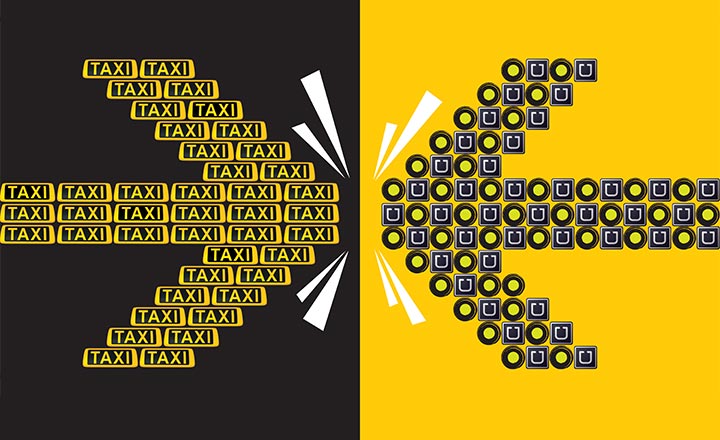

Apart from reduced incentives and the entry of several smaller regional players, the big change is on the fare front with Ola and Uber looking to increase their market share by eating into the business of conventional radio taxi and kaali-peeli fleets.

For its entry level hatchback offering, UberGo, the San Francisco-headquartered app-based taxi service, has raised the minimum fare in NCR from Rs.40 to Rs.60 in January 2017, while ride time charges were raised to Rs.1.5 per minute from the earlier Rs.1. It now charges Rs.6 per km up to 20 km and Rs.12 per km thereafter. While it may vary, the effective fare for a sub-20 km UberGo ride within Delhi costs Rs.12-14 per km.

Similarly, Ola’s entry level service, Ola Micro charges a base fare of Rs.40 in addition to a ride time of Rs.1 per minute, Rs.6 per km up to 20 km and Rs.12 thereafter. Ola already had created a category, Ola Mini, that directly competed with UberGo. But Micro was added last year to further undercut UberGo. This taxi category offers smaller cars such as a Hyundai Eon, DatsunGO, or WagonR for Rs.11-14 per km under 20 kilometres in Delhi.

But if one looks at government-approved fares for an A/C taxi in Delhi, the kaali-peeli taxis are authorised to charge Rs.25 for the first km and Rs.16 per km thereafter during the day. Prominent radio taxi players such as the Mumbai-based Meru Cabs charge Rs.69 for the first three kilometres (in Delhi) and Rs.23 for the remaining ride. Currently, the company is offering a discounted rate of Rs.16/km for bookings done through its app. Meru’s radio taxi offering is comparable with Ola Prime (A sedan with a base fare of Rs.50 along with Rs.10/km till 20 km and Rs.14/km thereafter plus Rs.1 a minute) and UberX (sedans). In the case of kaali-peeli taxis, the government-authorised Rs.16/km is sufficient to cover costs and make a profit also. Nilesh Sangoi, CEO of Meru Cabs, says, “Generally, their costs are lower as their vehicles are old and also they don’t have to drive down to pick up customers.” In the case of Ola and Uber, their entry-level offerings, Micro and UberGo, effectively charge anywhere between Rs.12 and Rs.14 per km.

On what the right fare should be, which would cover all costs and be remunerative for Ola-Uber drivers, Rajeev K Vij, a 20-year-old hand in the taxi industry and the founder of Carzonrent, a Delhi-based corporate car fleet company with 8,000 cars, had this to say. “The government rates have not come out of thin air. A sedan’s prescribed rate is Rs.23/km and that has been arrived at after adding fuel, maintenance, depreciation, driver earnings, margin, insurance, average running hours and many more parameters,” says Vij with a smile.

Meru’s Sangoi, too, concurs with Vij. “An optimum fare point will vary from city to city but it should be somewhere between Rs.2,500 and Rs.3,500, which a driver should get from commuters.” This will cover all costs, including fuel, maintenance, EMI, revenue-share [commission] among others.

Given that in metro cities, a driver can typically drive 100-120 km daily, the fare works out to Rs.20-Rs.25. “The overall distance could be 150 km, including the commute to home and pick-up,” says Sangoi. He feels that if a driver has to drive more than 120 km and eight hours a day inside a city, it is counterproductive for his health and safety.

An Ola Micro in Mumbai charges Rs.55 as base fare, Rs.6/km for the first 20 kms, and Rs.12/km thereafter and there is the Rs.1 per minute charge, too. Thus, a consumer bill for 20 km will work out to be Rs.235 or Rs.11.75-Rs.12/km.

Now, when we look at Ola’s minimum business guarantee numbers (incentive slab), a driver must reach at least Rs.2,300 per day as an optimum revenue point (see: A long drive). To get there, the driver will have to generate a customer bill of Rs.2,291 at least, at which point, Ola offers him a minimum business guarantee of Rs.3,400, and pays him Rs.2,720, after deducting its 20% commission. In the case of Uber, Jain states in the blog that 80% of Uber drivers, who are online for more than six hours a day, make anywhere between Rs.1,500 and Rs.2,500 after Uber deducts its service fee.

Bajaj from Matrix feels that even without incentives, most cabbies can clock Rs.1,800-Rs.2,300 a day, which totals to Rs.60-70K a month. “If you look at the EMI they need to pay, it is about Rs.12-14K; fuel cost is around the similar number. Maintenance costs will come to Rs.7-8K. If you do the simple math here, a driver will make Rs.25-40K without incentives,” he points out. But in order to generate Rs.2,291 at Rs.235 per hour, the driver needs 10 back-to-back one-hour bookings, which is an unlikely scenario. There are fewer bookings in cities outside of peak hours; one needs breaks, not to mention the traffic jams. Little wonder that several drivers end up slogging 15-16 hours to get to that mark.

Simply put, in an Ola Micro scenario (at Rs.12/km effectively), one needs to drive 190 km a day to reach the Rs.2,291 bill mark to take home Rs.2,720, which is almost double of what others in the taxi industry suggest as an optimum run in a city. So, the conventional radio taxi industry logically did a trade-off between kilometres driven and fare point. By doubling the Rs.12/km to Rs.24/km, a driver just needs to drive a comfortable and feasible 95 km a day. Not to mention that this covers all related costs as well.

Vij, whose fleet is dedicated to corporate clients, says, “In our case, our average transaction value is always greater than Rs.2,000. If a driver gets 1.5 transactions a day, potentially it’s Rs.90,000 per month business for the driver or owner of the car. After deducting all costs, one can make an average Rs.30,000 per month.” Of the 8,000 cars operated by his company, 95% are sourced from individuals or driver owners. “We have been aggregating since 2007,” he adds.

Managing drivers

While ANI Technologies launched Ola in 2010, Uber entered India three years later, and has scaled up rapidly in what it deems as a “top country” in its quest for global growth. It boasts of some 240,000 drivers in 29 Indian cities, while Ola claims a network of 450,000 drivers across 102 cities.

Sreedhar Prasad, partner, KPMG, feels that with more customers on-boarding the Ola-Uber gravytrain, the aggregators need to manage the driver side of the business correctly. “Cab aggregators need to get the driver-side of the model right. They can’t delay it because this may impact the trust factor. Also the moment rivals form a union, the situation will become tougher,” feels Prasad. But that is clearly not a concern for the aggregators. The silver lining here is that often, the drivers are not cab owners and are not under a single union, unlike their kaali-peelis and autorickshaw counterparts.

![###<b>"Incentives are normal in any new business. The strikes [by drivers] are happening now because the business is moving towards a more sustainable model" —Avnish Bajaj, managing director, Matrix Partners India (Photograph by Soumik Kar)</b>](https://s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/olb-data/outlook_20230628132815.jpeg)

Vij and Sangoi feel that if seen through simple business economics, demand (fare) and supply (of drivers) aren’t detached and fares have to cover the driver payouts. But what are the issues on the driver side? Why did both companies resort to huge subsidies in the form of incentives? Why promise Rs.100,000 a month when realistic incomes are less than a fifth for that vocation?

“For cab aggregation to succeed, you need to have drivers waiting outside your gate once you tap on the app,” points out Karthik Reddy of Blume Ventures, an early investor in TaxiForSure, which was later acquired by Ola. He further elucidates his point, “On the supply side (i.e. driver side), both companies were not getting consistent supply of drivers. Hence, huge incentives meant that supply became more predictable as the drivers stuck around with the aggregators.”

Reddy points out that the market was flawed. “Drivers were being overpaid. People who were capable of earning Rs.20,000 were being paid Rs.100,000. But I don’t think that was ever going to be the case. They were naive, if they thought so. Now, when those rates are falling, drivers are overcommitted or overspent or overleveraged.”

Bajaj agrees. “When the business started, in order to get drivers on the platform, they were given incentives which are normal in any new business. So, the strikes are happening now because the business is moving towards a more sustainable model,” he says. The incentives are now being aligned more towards kilometres and not the number of rides. It’s not surprising that for generating Rs.380 crore in revenues, Ola spent Rs.906 crothus incurring a loss of Rs.750 crore in FY15. These figures do not include financials of TaxiForSure, which Ola acquired towards the end of the financial year for $200 million in a stock and cash deal.

Justifying the lowering of incentives, Bajaj says, “The lowering of incentives is not unique to India, priming of the pump has to happen. When Coke and Pepsi were launched in India, they sold at Rs.5 a bottle — which didn’t even cover the cost of the bottle — to wean customers away from Thums Up. So that is to prime the pump and demonstrate better experience to customers. Once that is done, companies evolve towards more sustainable practices.”

Putting across Uber’s point of view, Jain states in the blog that because Uber is a two-sided market, it needs to balance the needs of riders and drivers. “Uber rolls outs incentives and promotions to introduce the service in new cities. Without doing this, it’s hard to ensure drivers are compensated for their time when few riders are aware of the service. As more riders use Uber, drivers are busier and can earn more. This in turn attracts more drivers, which helps guarantee faster pickups, and allows us to adjust incentives over time.”

Plump incentives being handed out by the two major app-based taxi aggregators has been a matter of concern for Samar Sangla, founder, Jugnoo. The Chandigarh-based autorickshaw aggregator operates in 35 cities, which is now also getting into cab aggregation. He feels that both players have been unethical in advertising inflated incentives. “Driving doesn’t require much of a skill and Rs.10-20K per month is a pretty reasonable pay in a country like India. I think it was driven by collective greed,” he says.

Jugnoo has plans to onboard distressed drivers for its taxi aggregation service in the future. “When I speak to autorickshawalas, I say, ‘Kaam dunga, paisa nahi dunga’ [I will give you work, not money]. Similarly, our strategy with cabs is to wait and watch. As soon as subsidies are over and real costs come into play, we will also start offering cab services.”

In addition to being attracted by short-lived incentives, many drivers also made poor purchase decisions, adding to their woes. Because they were getting loans facilitated by Ola and Uber, they picked up cars, which were slightly costlier.

Few years back, Meru and Easy Cabs deployed the cheapest car with highest mileage, Logan, which cost less than Rs.5 lakh. “Getting the cheapest diesel car with the highest mileage was the psychology of drivers in the pre-cab aggregator model days. Assuming the high earnings will continue to be what it is today, the drivers ended up buying cars that were expensive. Now, when companies are rejigging their models, drivers are facing difficulties because they fast forwarded their earnings, and changed their lifestyle,” says Prasad from KPMG.

In one of the driver orientations that Outlook Business attended at Ola’s office in suburban Mumbai, an Ola representative during a PowerPoint presentation mentioned that the incentive structure would keep changing depending on market conditions. More specifically, the structure would depend on what their rival was also offering.

Prasad says, “What it effectively means is that the drivers will get the same incentive but they will have to clock more trips which is difficult in India because of traffic. In metros, people don’t commute much outside of peak hours. Earlier they were doing 12-14 hours, now they will have to be on the road for much longer than that.”

Against this grim backdrop, some drivers and owners have started to look out for other avenues. Vij says, “Some owners have shifted their cars to our self-drive system, Myles, on a revenue-sharing basis because they found dealing with drivers a hassle.”

Optimum utilisation

Any aggregation business is an attempt to aggregate idle, unutilised, fragmented assets with the help of a platform. Singhla of Jugnoo feels that Uber has been a great disruptor and utilisation benefits could be substantial. “In case of autorickshaws, utilisation goes up from 30% to 80%, as soon as they are brought on a platform. In the case of cabs, it could move up from 30% to 50%,” says Singhla. However, unlike autorickshaws, a large number of additional cabs have been added into the system for the on-demand service. The asset addition comes with an additional recurrent cost (i.e. repayment), thus putting a pressure on revenue.

Do the utilisation benefits outweigh or even justify the costs involved in creating an active on-demand cab system? Does it bring down the fares for users in the long run? Sangoi of Meru feels otherwise, “Utilisation comes more as a result of network effect here. But it is definitely overhyped in terms of the efficiency it offers. Even before aggregators came, drivers were provided addresses from where to pick up customers. So, efficiencies did exist.”

He further feels that a lot of boxes need to be ticked to see a greater utilisation and, eventually, a low-cost breakthrough. Idle time of taxis will reduce when somebody has a lot of bookings coming their way and consumers find the prices lucrative enough than owning a car, and even lower than auto fares. “In the current scenario, there is a big mass of consumers and drivers whose economics work only because of incentives. That’s how the network effect comes into the picture. But it becomes unsustainable beyond a point because drivers cannot be driving more than 10 hours a day. Big incentives made slogging lucrative, but with normal payouts they may not utilise their vehicle,” feels Sangoi.

The other economics question is related to the very nature of an asset like a car. Is there an economic merit in utilising it over and above your own need? “There are some benefits of doing that, one is interest payment. The more you utilise, the faster you repay the interest. Similarly, parking costs are saved. But the downside is related to its finite life. Depreciation and maintenance costs are on per-km basis and the driver’s cost is based on the number of hours. I am not sure whether you save more, or destroy it early,” Vij thinks aloud.

Tweaking the model

Uber as an original idea was founded in a gig economy or a shared economy. It did so in a country like the US, where people already own vehicles and don’t mind driving part time to make an additional $20. India is different. Private vehicles are not allowed to ply on the Uber or Ola platform. Also, the drivers are often not the owners. Making car ownership a thing of the past — this dream is probably not for India. Both Ola and Uber have started their car leasing platforms to lease out cars to pull in more drivers. That doesn’t really make them an asset light technology company. Both players have tied up with OEMs such as Toyota, Tata Motors, and Mahindra & Mahindra to either facilitate drivers to buy vehicles or purchase vehicles for their leasing business at a good price.

“Under the lease model, typically a driver needs to make a deposit of Rs.10,000 and he gets a car. He needs to pay the company roughly Rs.850 each day for five years. They increasingly want to take this route,” says Agarwal of Chaalak Shakti. “Financing with the help of banks is being enabled to streamline the process of ownership for drivers. In the US, the economics and the paying ability are much higher. You are able to make $300 in a day. It is much tougher in India. It’s not the same math. You have to customise for local conditions,” explains Reddy.

While facilitation of financing doesn’t put any pressure on companies, leasing can have consequences. “If you give an asset to a driver-entrepreneur and he has to pay a fixed amount, as a smart entrepreneur he is going to juice it by running it 24x7 with two drivers,” says Vij, adding that hundreds of vehicles were returned to the aggregators for repairs, thus, frustrating their initiative. Furthermore, the strategy has led to conflict with disgruntled drivers, who claim that leased vehicles were given priority by Ola and Uber over other drivers.

Battling it out

With the cab aggregation business gaining momentum, the battle for survival has begun in the earnest. Both the aggregators prefer to call themselves as technology companies, though Sangoi of Meru feels otherwise. “Creating a platform is not difficult. The real issue is that companies continue to offer services at below-cost prices from that platform.”

While that might be the case, private taxi associations are realising that embracing technology is inevitable. The Delhi-based Chaalak Shakti claims that its service and experience for the customer, with its to-be launched app, will be on par with others. While Ola and Uber charge a commission of 20% and 25% respectively, amounting to Rs.12,000 to Rs.20,000 per month from the drivers, Sewa Cab will charge a fixed monthly fee of Rs.700. The app also has a ‘hail and go’ feature that allows a passenger to flag down a taxi on the street. On boarding the vehicle, the driver punches the customer’s mobile number into the app and the meter will start immediately. The union is also open to taking on all types of taxis under Sewa Cab, including tourist vehicles and kaali-peeli cabs.

On the pricing front, the union mentions that its fares will be competitive and transparent. It points out that the Rs.6 per km base fare of Ola and Uber actually works out to Rs.12-14 for Uber and Rs.14-16 for Ola without surge pricing. When surge pricing is taken into account, the average price between the two easily crosses the Rs.15 mark. But the fact remains that prices are still effectively lower than the current prices charged by private taxis in major metros. The Mumbai Taximen’s Union wants the upper limit for cab aggregators to be fixed at Rs.30 and the lower limit at Rs.28 per 1.5 km. Besides this, the union has also suggested additional costs of Rs.18 in lower limit and Rs.20 as upper limit on every additional km. A four-member committee is looking into the issue of fixing the maximum and minimum fares in Mumbai. Bajaj is more than happy about the development. He says, “Minimum fares would be brilliant for us. We won’t have to fight on the consumer side.”

In Mumbai, the government has introduced a City Taxi scheme that mandates cab aggregators to have a safety feature and vehicles running on clean fuels such as unleaded petrol or CNG/LPG. Interestingly, the scheme also allows kaali- peeli taxis to join any of the cab aggregators or create their own app platform. Swabhiman Sangathan Taxi union in Mumbai, which has around 22,000 kaali- peeli vehicles plying on the road, is opting to create its own app. Though media reports suggest that more than 50% of the taxis are likely to migrate to the two cab aggregators in the coming months.

On how they can match the technology giants such as Uber and Ola, Aggarwal of Sewa Cab says, “On the tech front, we think we have 90% of technology used by them. Google Maps and traffic congestion reports are available to everyone. Ola and Uber spend millions on their top executives, we save on that cost. They do a lot of analytics but a lean city-based point-to-point app doesn’t really need such sophistication. Taxi is a commodity, there is very little customer stickiness.” However, Reddy differs, “Stickiness gets built on reliability and experience. Ola and Uber understand that. Good luck to someone building that kind of reliability.”

Full throttle

In New Delhi, Uber was shut down for four days in February owing to driver protests. In Hyderabad, both Uber and Ola services were disrupted for a week around the beginning of the year. Bengaluru, too, has seen sporadic strikes and protests. Given the diverse profile of drivers and in the absence of a recognised union, Ola and Uber are unlikely to be fazed by such disruptions. Moreover, the High Courts of Delhi, Bengaluru and Mumbai, too, have advised the striking drivers to desist from such activities, thus proving to be a shot in the arm of Ola and Uber.

Industry insiders, too, believe that regulation is unlikely to be a spoilsport. Vij sees two reasons driving that. “The state has failed to solve the urban transportation problem in India, so when the private sector is offering an alternative, it is given a chance. Secondly, the involvement of a large number of drivers adds a political angle to it and regulators often decide to go soft on cab aggregators,” says Vij.

For now, Ola and Uber, on the back of investors’ money, are still holding sway over drivers with their incentive schemes. “I think they are playing to win the market. But any disruption of such magnitude is going to entail a bit of capital burn,” believes Reddy. However, Prasad of KPMG, feels the advantage won’t last long. “They can dictate the market but they can’t kill competition,” he says.

Not surprising that views are divided on whether the aggregators can retain customers when they increase fares. While Sangoi believes a set of customers have got used to the service, Vij feels that given that only a handful of cities have a history of cab culture, there is little loyalty among commuters. “Many new users might go back to autorickshaws and other modes of transport if fares are hiked,” says Vij. But Bajaj is not worried, “It is a whole new level of user experience and I don’t think people are going to go back. If you are willing to go in an auto, you would rather go in an A/C car and share it. You have a product, which is better and cheaper than an auto. And in that product, Ola is number one.” Uber, too, believes with sustained high demand from both riders and drivers it can shift from a start-up mode to a more sustainable business model.

In other words, the game now boils down to capital burn. Access to deep pockets and a brand give Ola and Uber an edge. Sangoi is unfazed though, “We didn’t get killed despite over Rs.600 crore being burnt every month between the two. Let the real costs come into play,” he quips.

As for the drivers battling it out for survival, they could well remember what Travis Kalanick told an Uber driver: “Some people don’t like to take responsibility for their own shit.”