It’s a puzzle made in jigsaw heaven. Once the pieces are put together, they connect seamlessly without any protruding edges, and the puzzle can be rolled up and placed in a cylindrical container without it falling apart. When completed, it forms a picture of the Amazon rainforest. After completing the puzzle, the players pick up cards with which they have to spot various characters and flora in the forest. The first one to identify the characters wins.

This is MadZill, a game offered by Bengaluru-based MadRat Games. It’s one of a new kind of skill-promoting games for children that are finding their feet in the ₹3,000 crore organised toys and games market.

Then there is Colour Scientist, from the Chennai-based Flintobox. This has an activity called My Colour Lab, in which — with the help of test tubes, colours, a paper burette and a beaker — the child learns how to mix colours in different proportions for different results.

MadZill and Colour Scientist are just two of the hundreds of such children’s games launched in India over the last two or three years. Spotting a lacuna in the market, a bunch of young, energetic entrepreneurs is writing a new story in the toys and games industry, thereby changing the proverbial game.

Marrying work and play

Traditionally, most games have either sought to provide entertainment without promoting skill development, or have focused purely on academics, with little emphasis on fun. These new games seek to do both, essential in a market that sees tough competition from tablets, cell phones and computers to grab the limited attention of children. One of the ways to do this, according to the founders of Flintobox, is to work through a subscription model, sending the child a new game every month.

Started by Vijay Babu Gandhi, Arun Prasad Durairaj and Shreenidhi SP in 2014 with an investment of ₹10 lakh, Flintobox was conceived when Gandhi was looking for educational yet fun toys for his four-year-old son. He couldn’t find any, prompting him to team up with Durairaj and build a prototype of a box-based game, which was then tested extensively with parents and teachers.

The company makes games for kids between 3 years and 8 years on the principle that this age group is where the child learns the most. It focuses exclusively on child development by zeroing in on fine motor skills, gross motor skills, vocabulary, imagination and sensory, cognitive, social and communication skills. “Each of our games is a complete set with something to create, explore and read, providing a good value proposition for parents. Also, the materials used are qualitatively superior to those of our competition,” claims Durairaj.

Another runner is Chalk and Chuckles. Owned by former finance professional Pallavi Agarwal and child psychologist Prachi Agarwal, the New Delhi-based company was set up about five years ago with seed capital of ₹25 lakh from their own money. The company’s games are backed by research in child psychology, neuroscience and reading from books and journals. The games have three levels, and there’s a twist in the tale every time a certain level is mastered.

MadRat, too, believes in the importance of child psychology in creating games. Set up in 2010 by Rajat Dhariwal and his wife Madhumita Haldar, IIT graduates and former IT professionals in the US, the company was born when the duo, while teaching at Rishi Valley School in Andhra Pradesh, realised that students with differing abilities can’t all grasp dull subjects like science and math. Knowing that play makes a huge difference in learning, they sought to modify teaching through role-playing and games.

Learning from the best

Dhariwal and Haldar were inspired by a student who had a poor academic record and who received poor reviews. The child had a knack for sports though, and Dhariwal realised that the child possessed kinaesthetic intelligence (a quality of sculptors, painters, etc, where you perform better when learning through physical activity and using hands) in abundance. Dhariwal asked his students to prepare models of what they understood of science concepts, and here, the child performed admirably.

This realisation — of the importance of play — coupled with the opportunity in the market, led to MadRat Games, which introduces an Indian context to its games. Their first, Aksharit (an Indian version of Scrabble), is the first word game to use Hindi. It has tiles designed with mantras and is used in over 300 schools to improve language skills.

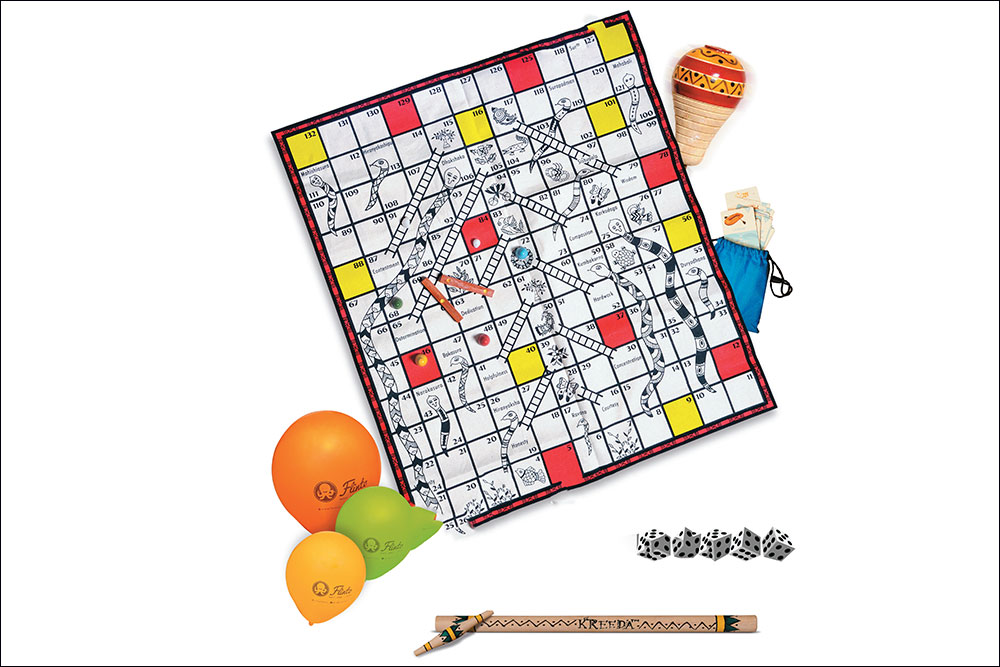

The Indian context, in fact, is what inspired Vinita Siddhartha to set up Kreeda Games. “I was an entrepreneur by accident, not by design,” she declares. Siddhartha studied journalism in the US before returning to India and setting up a content writing company. A client asked her to write on traditional games, and this piqued her interest. She made eight traditional games and sold them in a retail outlet in Chennai, and, seeing their sales, she set up Kreeda with a capital of ₹1 lakh in 2002.

Kreeda is different, from the packaging, materials and design to the emphasis on traditional games. For instance, their games are printed on canvas and the dice are wooden and long, and most of these are made by craftsmen.

Then there’s Chennai-based Skill Angels, which believes that fun isn’t just for kids. Founded in 2013 by Saravanan Sundaramoorthy and Kalpana Murthy, it produces children’s games along with those used in offices to sharpen employees’ skills and the employability of interviewees. “Since we have 500 online games, our focus is not on introducing new games, though we will do that in a reduced manner, but rather focusing on child development, which is why we have a unique offering for every grade,” says Sundaramoorthy.

For adults, they have a game called Team Up, which features a rectangle that has to be divided into four equal parts in less than a minute, promoting delegation and problem-solving among managerial staff. Its games have a focus on memory, problem solving, emotional development and linguistics, with a special focus on cognitive skills.

Most of these companies go through an extensive process, employing designers and building prototypes, which are tested with children to see if they are engaging. To ensure that their games are enjoyable, they involve child psychologists and developmental paediatricians. Skill development, though, remains the most important rule of the game. Skill Angels, in fact, has filed an international patent on skill-to-curriculum mapping, a process to show how skill development leads to an enhanced knowledge of the curriculum.

The money game

In an industry full of players, it becomes essential for every company to make its mark. Tying up with schools is a common tactic. Skill Angels offers its games through a B2B2C platform to 35 schools and play schools. It also holds the Super Bowl Series — online gaming contests held in engineering colleges. The company has reported ₹1 crore of revenue to date and hopes to clock in ₹3 crore by FY16. It aims to achieve this by gaining maximum publicity from the Super Bowl Series, going B2C and also tying up with a couple of channel partners such as Parent Tree and Amar Chitra Katha. Skill Angels markets itself through blogs and a big Facebook presence as well as newspaper ads, and has so far spent approximately ₹10 lakh on marketing. It has yet to break-even, but Sundramoorthy expects this will happen by FY17.

The Agarwals of Chalk and Chuckles, too, are realistic enough to realise that they can’t take on the marketing might of larger players such as Funskool and Mattel, so, they are banking on a unique marketing gambit. “We are working on getting schools to adopt our games as curriculum. That way, children will want to buy our games. We also plan to hold unique events, like collaborating with children’s book writers to talk about the skills required in child development and introduce our products as a match,” says Pallavi Agarwal.

The Agarwals are also in talks with Amazon and Google to lend them a brand page, and Chalk and Chuckles is already present on Facebook, Pinterest and Twitter, where it is looking to expand.

Similarly, Kreeda, too, gets the word out through promotional events at schools, companies, exhibitions, etc. Siddhartha isn’t looking at typical corporate marketing, as she feels the traditional quality of the game is so unique that sales happen through referrals, especially on Facebook and Twitter.

Kreeda’s games are not designed specifically for children — though they cater to both children and adults. “Our games don’t have to be twisted much to produce learning. There is a lot of subliminal learning happening,” says Siddhartha, who works with a team of five others. Kreeda has, so far, introduced 20 games, priced between ₹150 and ₹850. Though the company has tied up with Flipkart and Amazon, it mostly sells via outlets such as Landmark and Odyssey. Siddhartha also plans to set up an online payment gateway soon.

Kreeda has broken even though it had a rough past year, when the market was dull, and its supply chain mechanism faced a lot of problems. Two of the company’s suppliers went bust and it had to go back to the drawing board, affecting sales. Kreeda shares 40% of its MRP with retailers and as a percentage of total top line, it works out to 22%.

Revenue sharing for Chalk and Chuckles is similar. The Agarwals pay less than 40% of the margin to mom and pop stores, while larger stores charge roughly 50%. The retail model has worked for them because their games, priced between ₹199 and ₹799, are different from mass-market toys, says Pallavi. Her company, which is eleven-member strong, hopes to break even this year. The ₹1.3 crore company (in FY15, with 32% coming from exports) has seen revenue climbing from ₹85 lakh in FY14 (25% from exports) and is looking to achieve ₹4 crore next year. This is not just plain optimism: Chalk and Chuckles has confirmed orders worth ₹1 crore from new customers in new countries, and another ₹1.35 crore from repeat customers in the US, Israel and Spain. The rest, they believe, will come from domestic customers and contract manufacturing for clients overseas.

The stand-out factor

Marketing posed a different issue for MadRat, set up in 2010 with ₹35 lakh from friends and family. The company, which has launched 85 games, priced between ₹500 and ₹1,000, was suffering from poor brand recall value. This year, it plans to launch a new game category with 10-15 games.

“The reason for this shift was poor brand recall among parents. Without an extensive ad budget, we decided to focus on developing and marketing a product category, rather than selling 100,000 units of 50 games, for better brand awareness,” says Dhariwal, adding, “We aim to scale up MadZill and will look to VCs to fund that.” They are also looking to rebrand and relaunch My Toy Factory and Aksharit.

MadRat has a staff strength of 52, of which five — apart from Dhariwal and Haldar — are involved in designing. The company has 30 distributors and sells through 10,000 outlets across the country. It also has a presence on Amazon and Flipkart, but this contributed less than 5% of its total revenues of ₹3 crore in FY15. They share close to 25% of the MRP with retailers, says Dhariwal.

MadRat recently raised $1 million (₹6.2 crore) from Flipkart co-founders Sachin and Binny Bansal, and IT firm Global Logic to promote branding, promotions and media campaigns after this month. But even after five years, the company hasn’t broken even, and Dhariwal doesn’t see it happening anytime soon. This is because their first three years saw a lot of experimentation, getting to a ₹50 lakh top line. The last two years were when the company went into retailing and built a B2C business, but so far, the market has not been very responsive. It has revenues of ₹3 crore in FY15 and looks to triple it to ₹12 crore in FY16, by focusing heavily on brand building in MadZill, where its goal is to touch 100,000 units, fetching ₹4 crore. They will make a foray into the US and have a brand-building exercise this year.

MadRat is involved in several pilots with schools, along with tie-ups with theatres to show its ads. It has also collaborated with Amazon and Flipkart to display its banners, and is now undertaking a brand-building exercise, through social media and offline, promoting an event that will feature the world’s biggest jigsaw puzzle. For this, it has roped in a senior brand manager from ITC, and the ad spend on this will be over ₹1 crore.

Yet, he believes the company has been a success, thanks to their background. “Our IIT exposure gave us problem-solving skills. My experience at Amazon taught me the importance of innovation and product design as differentiating factors. Also, being with kids daily and designing curriculum at Rishi Valley taught us what really motivates them,” he says.

Rajul Garg, founder, Global Logic, which funds startups, thinks Dhariwal’s enthusiasm isn’t misplaced. “MadRat has a strong team and an innovative suite of products. It is trying to re-imagine a dinosaur market in a modern way. There is innovation in technology-based games, but not enough in the technology behind gaming, which is MadRat’s focus,” he says. But, he warns, “Board games haven’t seen much change in 30 years. All the innovation in other areas is the big challenge and the opportunity. The end user’s acceptance, and hence a resurgence of this category, is crucial.”

Changing the rules

Speaking of shaking up the market, Flintobox’s business model offers a refreshing take on the traditional child-takes-parent-shopping concept. The 15-member company works on a subscription model. The games — a different theme every month — are delivered in a box to parents. On a monthly basis, a one-month subscription costs ₹1,095, a three-month is ₹995, and a six-month subscription is ₹895.

Flintobox currently ships to 280 towns and cities in India, and has sold 15,000 boxes. “We plan to expand more aggressively in the categories we are present in and hopefully reach 50,000 boxes a month. Our products are tailored for kids between 3-8 years, but we would like to provide a box for kids below 3 years as well. We will also be present in some international locations in 3-5 years,” says Durairaj, who relies heavily on social media to promote Flintobox.

The company has already had one round of funding by GSF India and has also roped in a German angel investor, Asian ECommerce Alliance GmBH (AECAL). In all, it has raised ₹1.89 crore, and talks are on with investors for the next round of funding. Durairaj expects the ₹6.3 crore company (in FY15) with 45% gross margins, to clock revenues of ₹25.2 crore in FY18. The company has 12,000 customers and the addressable market size for children in this age group is 4.5 million. With no direct subscription-based competitors in the educational games segment, Flintobox has a huge advantage. “Flintobox has an excellent management team and we believe its games are the perfect tool to help parents engage with children in a productive manner,” says Peter Kabel, director, AECAL.

While Kabel is gung ho on Flintobox’s prospects, he offers a warning too. “Flintobox has a pretty limited range of product offerings and needs to expand its target age groups as well.” The real question is whether the company’s planned foray into tier 2 and 3 cities will work. “Flintobox will have to change its business model if it wants to penetrate deeper into India. This price point will not work in those areas. Secondly, it might have to consider going offline and changing its subscription-based model. How it manages retail in such a scenario remains a question mark,” says Ankur Shrivastava, founding partner, Globevestor, a key investor in Flintobox.

However, Flintobox is not looking to scale into tier 2 and 3 cities till it reaches the ₹25 crore mark. When it does so, it is neither looking to reduce price points nor go offline as Durairaj believes there is enough consumption spending in those areas, and that parents consider this an investment. This, together with the future of the internet, means Durairaj sees no reason to be afraid.

What lies ahead

For all the optimism generated by the success of these entrepreneurs, they won’t find the going easy forever. The Indian toy and games market is growing at a double-digit clip. The market is highly fragmented with a large number of players in the unorganised space having a turnover of less than ₹10 crore per year. In the organised space, there are two major players — Mattel India and Funskool (Hasbro, Lego etc have been integrated into Funskool). Funskool is growing at a 22% CAGR and has a 15% market share. Mattel had a 10% market share but owing to a top management exodus, it saw a 20% de-growth in FY15 and now has a 7-8% share of the market.

“Awareness among Indian parents as to the benefits of games in a child’s development is very low, unlike the west. Secondly, with differing tax rates in every state, retailing and distribution is not easy,” says Baby John, CEO, Funskool India. “The penetration of toys and games remains an abysmal at 0.5%, and given the demographic dividend of the country, there is a huge opportunity for growth.”

Globevestor’s Shrivastava cautions that the success of the pioneers breeds a lot of new entrants and that could lead to more competition in an already heated market. Chinese toy manufacturers have been flooding the market with cheap toys, which have impacted the growth of the organised players. While Funskool’s John does not see MadRat, Kreeda and the rest of the pack as a competitive threat, he says, “There is enough room in the market for all to grow. Secondly, we keep innovating and introducing new games. The bigger threats today are tablets, TV and computers.”

While there is no doubt that tablets, TV and computers have emerged as serious contenders for our children’s time, companies like these clearly fill a void for parents looking for games that go beyond the ordinary, focusing on skill development. While it is still early, there is enough room for them to grow revenues many times over and once they scale up, they could make attractive acquisition targets for large toy manufacturers or educational companies looking to fill the gap in their offerings. For these companies, the fun and games have just begun.