A quiet revolution was taking place on India’s roads in 1983. On December 14, the Maruti 800 was rolled out, offering an internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle at an affordable price to middle-class households. The small car with big dreams paved the way for mass adoption of ICE vehicles and changed the dynamics of the auto industry.

More than 40 years later, the government is planning a second coming in the automobile sector—this time through the mass adoption of electric vehicles (EVs). Part of this strategy is 30@30, which aims at a 30% share of EVs in new sales by 2030. Automakers are already moving towards electrification; several have announced phase-out dates for ICE vehicles.

In India, Suzuki expects 15% of its sales to come from EVs by 2030. Tata Motors plans to achieve 50% sales from EVs, globally, by the same year. At a convention of the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM) in September, Union transport minister Nitin Gadkari said the EV market will have 1 crore annual sales by 2030. But a number of hurdles have to be crossed to meet this ambitious target.

Facing an Obstacle Course

Among other initiatives, the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan announced in 2020 includes a vision for energy independence by 2047. The government also launched a production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme to boost EV manufacturing and approved an EV manufacturing scheme in March 2024 to give impetus to its Make in India initiative.

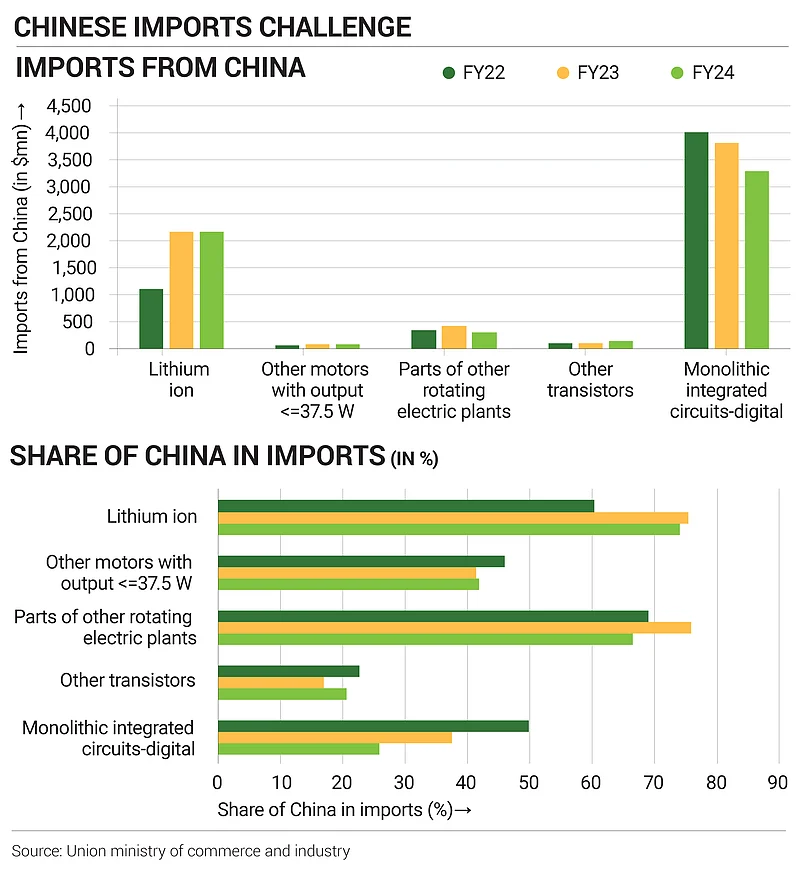

The plethora of schemes aside, the EV sector is still some way off from becoming “atmanirbhar”. Supply of raw materials, technology and import dependence, particularly on China, have been consistently rising. A Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI) report warns that China’s automobile industry, buoyed by substantial state support, has rapidly advanced in EV technology, making it a leading exporter of EVs and related components.

The Economic Survey-2024 suggests that India should welcome Chinese investment and reduce imports from the country, especially since the US and Europe are shifting their sourcing away from China. Data collated by the Automotive Component Manufacturers Association (ACMA) shows that China accounted for 29% of all automotive exports to India in the financial year 2023-24.

Added to this are hurdles closer home. “Price, choices, driving range, charging infrastructure are barriers. The PM eDrive Yojana has allocated money [establishing public charging stations], so I think this should start becoming the mainstream choice,” says Shailesh Chandra, president, SIAM.

Anxiety around the battery and price points, in particular, limit customer interest. “A key challenge is the high initial cost of EVs, which discourages consumers who are not yet willing to pay a premium for sustainable mobility options. The biggest challenge is myths surrounding EVs, like low battery life and residual value risk, which dampen customer sentiment,” says Santosh Iyer, managing director and CEO, Mercedes-Benz India.

China’s Global Monopoly

China emerged as a dominant force in the global EV market in 2023, exporting 1.6mn EVs valued at $36.7bn, says a study by GTRI. The European Union (EU) and the US were significant buyers, with China exporting EV parts worth $19.5bn to the EU and 438,000 EVs valued at $9.1bn to the US.

“It is not only India, but the whole world that is dependent on China for electric battery supply. China wants to supply the chassis fitted with battery and motor that account for more than 50% of an EV’s cost,” says Ajay Srivastava, GTRI founder and a former Indian Trade Service officer.

Lithium reserves, the critical resource in production of batteries for EVs, are present in parts of Africa, Australia, Chile and Argentina. China, however, has tapped most of these areas and taken several mines on lease. “Thirty years back, in the early nineties, China went around Africa and Latin America and took lithium, cobalt and other precious metal [reserves] on long lease for 50–60 years. They have secured the supply of these metals. A few others also have access, but nobody has the technology to process this mineral. China has absolute control over cobalt, nickel and lithium, metals used in making of the battery,” says Srivastava.

This is a major stumbling block. In February 2023, the Geological Survey of India (GSI) found 5.9mn tonnes of lithium in Jammu and Kashmir, but there is yet to be any successful bidding for the reserves. “China produces more than 80% of the world’s [EV] battery. The rest of the world accounts for 20%, but it is comparatively more expensive,” adds Srivastava.

As much as 70% of an EV's cost is the battery and components produced by China. “The biggest hurdle will remain manufacturing cells, which requires a minimum investment of Rs 5,000 crore for setting up a plant. For making a large investment like this, India needs to have a big market. This is the chicken and egg situation that needs to be resolved,” says Ajinkya Firodia, managing director of Kinetic Engineering, an EV manufacturer.

Prohibitive Input Costs

India’s heavy import dependence, particularly on China, explains the high input costs for EVs, says the GTRI report. Global supply chain fluctuations exacerbate the problem, as China dominates global battery production capacity.

“Geopolitical developments, such as the Iran-Israel conflict, have also impacted industrial metal markets. The US and UK have imposed fresh sanctions on Russian aluminium, copper and nickel. As a result, countries such as China, India and Turkey are expected to absorb more Russian metals, potentially at lower prices, but this could still drive up input costs,” says Saket Mehra, partner, auto and EV industry leader, Grant Thornton Bharat.

As input costs go up, so does the end price. Data from the Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations (FADA) in October shows that EV sales have dropped nearly 8% on a year-on-year basis. High EV prices coupled with few charging stations and low access to subsidies make the vehicles less attractive for buyers. As sales fall, profitability takes a beating.

In August 2023, a report brought out by the Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles (SMEV) stated that EV original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) have suffered losses of Rs 9,075 crore after the government put subsidies on hold for 22 months following the alleged EV subsidy misappropriation scam.

“But primarily, scale, relatively slower penetration of electrification across segments and therefore slower investments by OEMs and Tier-I suppliers have led to a certain amount of dependence on imports,” says Rahul Mishra, partner, automobile sector at global management consulting firm Kearney.

Tech Matters

Dependence on China also extends to technology. Experts say that though Germany and the US have similar technology, the Chinese have been at the forefront of developing EV technology—and consequently, the components that make up the EV environment.

“China has been an early adopter of EVs and as a result, whether it is two-wheelers or cars or buses, China has the largest production and sales and therefore the supply chain is very well-established,” says Kavan Mukhtyar, partner for automotive sector at the financial advisory services firm PwC.

Could India procure technology from Western countries? Experts seem to think not. “In India, we need affordable price points. It can’t be at European or American prices,” adds Mukhtyar.

As the US, Canada and the EU increase tariffs on China-made EVs, China is moving its production and assembly units to other countries, starting with Asean nations and India. “As part of the effort to bring more of the value chain into the country, we are also looking at investments [in overall imports of technology],” says Amardeep Singh Bhatia, secretary, Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT).

Industry bodies ACMA and SIAM agreed that India has to curb import dependency. One way to do it is enhancing localisation. The combined pressure of a falling rupee and uncertain global outlook also makes lowering import dependence an imperative. “Any fluctuation in forex has an impact, but I would say that's the reason the government has the PLI scheme. Hopefully, in the next two to three years, cell manufacturing will start in a big way in the country,” says Chandra.

Experts acknowledge that the government is trying to lower imports. “It [government] is making international agreements to secure lithium and rare earths. It has rolled out the PM E-drive scheme. It has the PLI scheme. The government is pushing for us to be part of the global value chain,” says Vinnie Mehta, director general, ACMA.

The launch of the Critical Mineral Mission is also expected to be a shot in the arm for domestic production. Will the efforts pay off? Only time will tell.