Tunnu is just six years old, but he is already part of a group of young children that walks on a treacherous path every day to reach an underground coal mine in the Dhanbad area of Jharkhand. Through a cave-like entrance, the children are greeted to many levels of mines on the steep sides at different heights—the closest one from the top being about 50 metres below the ground. The way down to the mine is so dangerous that one wrong step can cost the little Tunnu his life.

“We break coal and fill 50 to 60 kilogrammes of it in a sack. Older people lift the sack on the head and carry it out to their houses,” Tunnu says. He adds, “A guy comes on a dumper on certain days in a week and collects these sacks from us at around Rs 50 per sack. We are told that this coal is taken to other states, like West Bengal and Bihar, for sale at a higher price.”

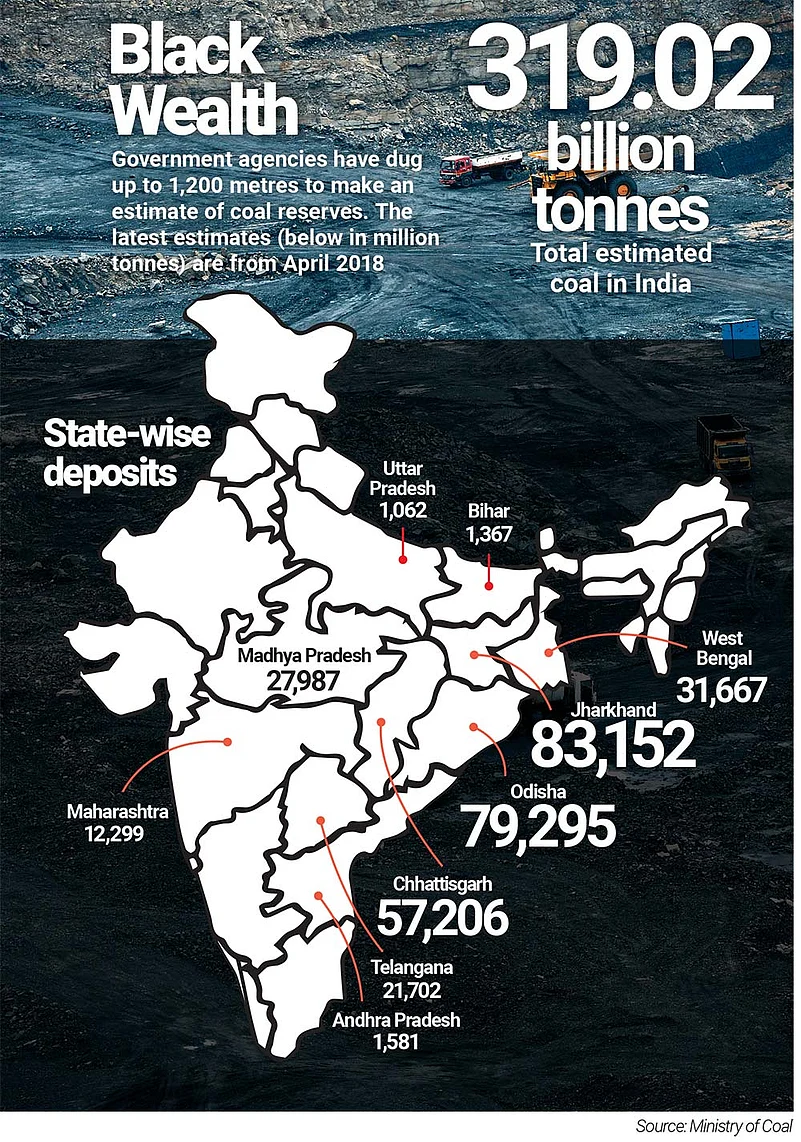

People have been losing their lives in these unsafe and illegal mines for years now, but making a living in some of the poorest regions in India requires one to overcome the fear of death. Coal has been the lifeline for millions of people in Jharkhand—a state rich in natural resources but also the third poorest in India with a per capita income of less than $2 per day—and its neighbouring states for over two centuries. However, over the next three decades, their lives are going to change.

At the UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) held in Glasgow last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi made five promises to the world: India’s non-fossil fuel energy capacity will touch 500 gigawatts (GW) by 2030; India will meet 50% of its energy requirement from renewable energy; there will be a reduction of total projected carbon emissions by one billion tonnes by 2030 from the 2021 level; the carbon intensity of the economy will be reduced by 45% by 2030 over the 2005 levels; and, India will become a net-zero economy by 2070.

To meet these targets and other ambitious goals to make its economy green, India will have to phase out coal as a source of fuel for power plants and other industries. That, in turn, will necessitate shutting down of India’s entire coal economy, which means by the time Tunnu enters his teenage years, India would have shut many mines that have provided livelihood to people for generations.

This scenario casts a shadow of uncertainty over the future of the ones involved in India’s coal economy, which generates billions of dollars every year through legal and illegal mining activity.

The numbers are mind-boggling. According to estimates, there are as many as 3.6 million people directly and indirectly involved in India’s coal economy. These include permanent and contract workers in government-owned Coal India’s coal mines, employees of coal-based power plants and the Indian Railways that transports coal to different parts of the country.

If we take into account the informal and illegal coal economy, including people involved in allied economic activities, like the hotel industry, catering, etc., the number touches 15 to 20 million across the six coal-bearing states of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, West Bengal, Telangana and Madhya Pradesh. For comparison, this number is equal to the population of Sri Lanka.

India is already struggling to generate jobs for its youth. When the National Democratic Alliance government came to power in 2014, it promised to create two crore jobs every year. Today, in its second term and the eighth year of its rule, it faces the criticism of falling short on this front. The Covid-19 pandemic took India’s unemployment rate to a 30-year high, forcing a large chunk of the Indian population to survive on just the free foodgrain provided by the government.

The Human Cost of Going Green

Coal has come to be known as the fuel that built the modern economy of the world. In India, the first coal field was mined in 1774 by the British in West Bengal’s Raniganj. The fuel, also known as black diamond, continued to be the bedrock of independent India’s growth.

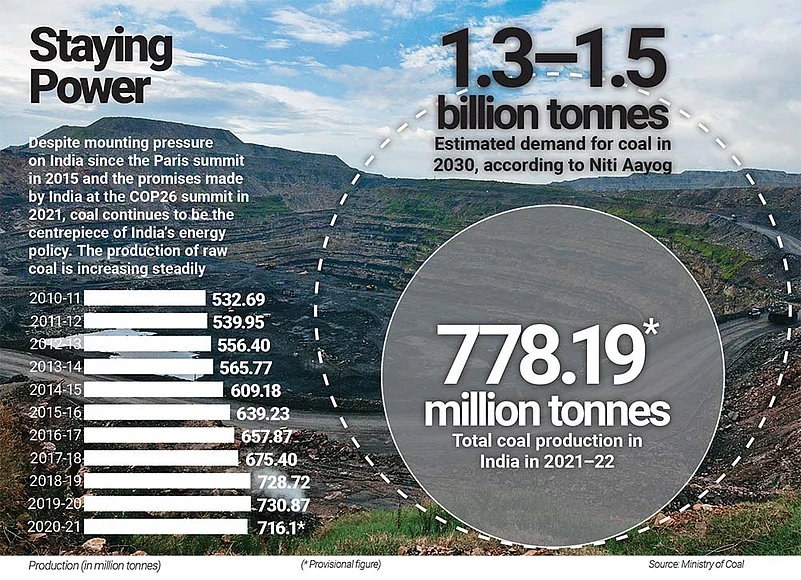

While the British used private contractors to mine coal in India, there were two government undertakings in the business of coal mining—Singareni Collieries Company Limited and National Coal Development Corporation. To meet the increasing demand of coal for the industry and control accidents in the mines, the Indira Gandhi government nationalised the coal sector from 1971–73, giving birth to the world’s largest coal mining company Coal India Limited (CIL). In 2021–22, India saw the production of 778.19 million tonnes of coal wherein CIL and its subsidiaries accounted for 622.634 million tonnes.

Today, the coal sector in the country has the impression that was envisaged at the time of coal nationalisation. Most of coal is mined by Central and state government-run coal companies. Add to it the role of the Indian Railways, which transports about 60% of the coal produced in the country and which enables it to earn substantial revenue, the coal industry can be called a true public sector.

All coal mining companies—private ones for captive use as well as government owned—pay taxes and royalties to the Centre as well as state governments in at least nine states. According to a research paper written by Sandeep Pai, a just energy transition expert with The Centre for Strategic and International Studies, in 2019, CIL paid around Rs 50,000 crore in total taxes and royalties to the Centre and state governments and district administrations.

Royalties paid to the district mineral funds are used for projects focused on improving health, education and community-based needs of the areas where coal mines are located. A large part of the development work is taken care of in these areas through the funds provided by coal mining and power companies.

Apart from this, there are local welfare schemes as well as corporate social responsibility initiatives by companies—2% of a company’s annual profit—that help in the areas surrounding mining activity. In the absence of coal mining activity, not only will lakhs of people lose their jobs, but several welfare projects that benefit the residents in the vicinity will also be affected.

Consider the case of the Tetulmari coal mine in the Dhanbad district. After the mine was closed last year due to a land dispute, over 700 casual labourers have become jobless and 5,000 members of their families are struggling to make ends meet.

Ashok Thakur, who spearheaded the fight on behalf of Tetulmari mine workers, says that to survive, many mine workers have become labourers in nearby cities while some have no option but to steal coal from the abandoned mines and sell it in the illegal market.

Ganesh, who makes a living by working in the illegal mining ecosystem in Jharkhand, says that he manages to make Rs 200 to Rs 300 every day through the mines, but even this small amount is not a regular income. “Some days, we make Rs 1,000 as well, but on other days, we draw a blank,” he says.

“If mines close, we will have no option but to beg or starve to death, as illegal mining is our only source of livelihood,” rues the 22-year-old worker, unaware about the international consensus against the usage of coal as a fuel to bring down the carbon emissions. He finds it hard to believe that these mines could be shut in the coming years—majorly due to the money involved in the activity.

Thakur says that the workers who are on the payroll of coal companies do not get impacted because they still draw their salaries regularly, but daily labourers are adversely impacted. “Some of them have even stopped sending their children to school, because they do not earn enough money. They travel several kilometres in the city to work. What options are they left with?” he asks.

The story of the Dobari coal mine in Jharia, which falls in the same district and was closed down a few years ago, is similar. Small tea shops and kiosks that sold food for morning breakfast and lunch in the area immediately closed down because they did not get enough customers, say locals. Like Tetulmari, some labourers have turned to illegal mining here, too. “Now, coal companies treat residents as thieves, and the security force deployed to secure mines often beats youngsters. It broke down a temporary shelter which was used to run a school,” says Deepak Kumar Saw, who runs a non-governmental organisation (NGO) called Nand Care Foundation to teach labourers’ children in the coal mine areas.

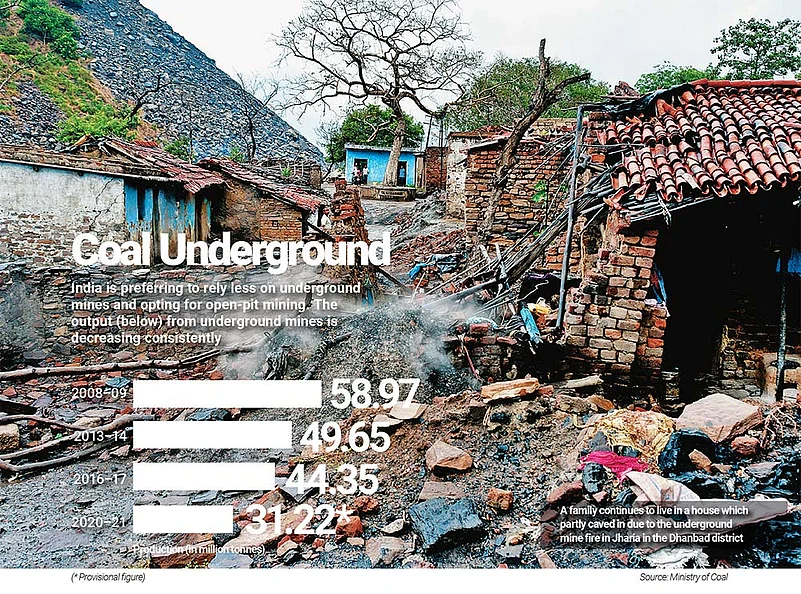

The coal mines in Jharia face a peculiar problem. Several mines have been burning for over 100 years, and the fire has spread underground to a large area. No one knows how exactly it started. Some say that the Britishers, while leaving India, put the mines on fire, while according to others, unscientific handling of mines and prolonged exposure of coal out in the open caused the fire to start. Besides Jharia, Raniganj also faces a similar problem, and all efforts to douse the fire have been unsuccessful.

Many villages in Jharia are situated over the burning mines. In many places, harmful smoke emits from the ground. Many houses have caved in, causing loss of life and property. “During the rainy season last year, half of my house caved in the ground. I lost my mother-in-law in that incident. Now, I live in half-a-portion of the house that still stands with my two daughters and wife,” a local resident tells Outlook Business, adding that he knows that it is life-threatening to live like this, but he has no alternative. It was scary to see the family living in a house where smoke still emerged from the broken portion, suggesting that the fire is raging below the house.

In Madhya Pradesh’s Shahdol district, NGOs working with coal miners say that more than half-a-dozen coal mines were closed in the district five years ago, and its impact can be seen in the people living in the area. “You will be surprised to know that hospitals had to cut down their staff and the number of doctors because company-employed mine workers migrated to other places and patient visits in hospitals reduced drastically,” says Rakesh Prakash Pandey, who is associated with NGO Child Rights and You that works for poor children.

Activists working in areas with abandoned mines say that the mine workers employed with the government coal companies are the ones that mainly migrate to other places because they get their salaries and benefits. Casual workers either head to other mines in the vicinity or look for alternatives of earning money. Very few of them want to leave the community and migrate permanently to cities.

When mines close down, labourers either head to other destinations or indulge in petty crime like stealing coal, says Pandey. “In fact, the problem of illegal mining has emerged from joblessness due to closure of several mines,” he adds.

How India ensures the transition of its workforce—from the fossil-fuel economy to one that runs on renewable sources—will decide whether it can meet its long-term goals around poverty eradication and development, says Suranjali Tandon, assistant professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy. “The just transition objectives correspond closely to those of the sustainable development goals that include poverty elimination and reducing inequality, apart from climate action and affordable and clean energy,” she adds.

Performance Pressure

Prime Minister Modi was under immense pressure from the Western block to commit to stringent targets before the COP26 conference. Just before the climate talks, a study by Paris-based International Energy Agency suggested that for the world to meet its climate targets, India, the third largest polluter in the world, needed to ensure that its “CO2 emissions never return to 2019 levels at any point”.

This meant that India will either have to turn green faster than anyone can imagine or compromise with its economic growth. While the West focuses on India’s current level of carbon emissions, it ignores the fact that India has accounted for just 3% of the historic energy sector and industrial process since 1850. On the other hand, on similar parameters, the share of Europe and the US stands at 30% and 25% respectively.

Between India and the West, there is a stark difference in the cost of transition to the green economy. About 40% of India’s population, or 52 crore people, lives in states with low per capita income. With a per capita income of just $2,277, Indians are 16 times poorer as compared to Europeans.

Given the total size of the Indian economy, it will be difficult for the Centre and states to manage the transition of coal-dependent population smoothly. As far as international help is concerned, developed nations have failed to keep their promise over the last decade. At the COP15 summit in Copenhagen in 2009, richer countries had promised to provide $100 billion each year by 2020 to developing nations for meeting transition goals, a promise which was never kept.

Vijaya Ramachandran, director for energy and development at US-based think-tank Breakthrough Institute, says, “The West is being selfish while negotiating climate talks. Their standards of living are in stark contrast to the people living in India. To lift people out of poverty in India, the government will need to provide seamless power supply to agriculture, industry as well as the services sector. If the West wants India to turn green, it must be willing to pay the cost.”

In April this year, several Indian cities and rural areas saw long power cuts due to an acute shortage of coal in power plants. The peak power deficit was reported at 10.29 GW, causing financial loss to industries. The situation was so bad that the government had to ask CIL to float a tender to import expensive coal to meet the coal demand in the country, forcing it to lift the self-imposed ban on coal imports.

Since India, with its domestic resources alone, will find it difficult to fund the transition, the Centre will have to be smart enough to strike a deal with the West.

Todd Moss, a former official at the US State Department and director of the Energy for Growth Hub, is of the view that India needs to seek something similar to what South Africa got from Western nations last year. The African country got a $8.5 billion financial package from the US, France, Germany and the EU during the COP26 conference to shift away from its coal-based economy.

“Unlike the $100 billion in global climate funding that was never met, South Africa’s deal is very specific and has mutual responsibility for who pays for what. Though the amount of the money promised in that deal is very small compared to what India will likely need to reduce its coal dependence, the model might be very useful,” says Moss.

Planning the Tectonic Shift

Experts say that in the past 72 years, India has been able to extract only 17 billion tons of coal, and even if it extracts one billion tonnes every year, its coal reserves will last for another 300 years.

Samiran Dutta, CMD of Bharat Coking Coal Limited (BCCL), feels that there is no threat to jobs of professionals and workers engaged in coal mining, because with the increase in energy demand, the production targets of coal will not be affected. “Today, coal accounts for 70% of our energy demand. This share will gradually come down, but in absolute terms, the coal production will keep going up by 2040 or 2050 because of increase in demand for energy,” he says, adding that his company has mitigation plans in place to meet the 2070 target of phasing out thermal power. Moreover, he adds, most employees will retire by then and the new recruits could be adjusted in related areas, like the solar sector in which BCCL is diversifying.

CIL, a maharatna public sector undertaking (PSU), has already started closing some of its mines. Centre’s estimates suggest that as many as 293 mines under different subsidiaries of CIL are already shut. The numbers are only going to increase in the coming years.

Realising the enormity of the task at hand, the Ministry of Coal, in an unprecedented move, is reportedly working on setting up a “just transition” division. Its task will be to plan the transition of coal-dependent states into the post-fossil-fuel economy where there is no money to be made from coal extraction. In October, it announced, “The Ministry of Coal is in the process of finalising a robust mine closure framework [with assistance from the World Bank].”

The World Bank has already shared a preliminary project report with the Union Ministry of Finance. The World Bank will create a detailed project report by the end of this year after consulting with stakeholders like power and mining companies and policymakers.

The World Bank has committed around $1 billion so far but experts believe that this is 1/1000th of the amount India will need in aid by the end of this decade for just transition. “India will need $1 trillion by the end of this decade from the global community in aid. Given the size of the Indian economy dependent on coal, anything less than that will result in the suffering of the poorest people in India,” says Ramachandran.

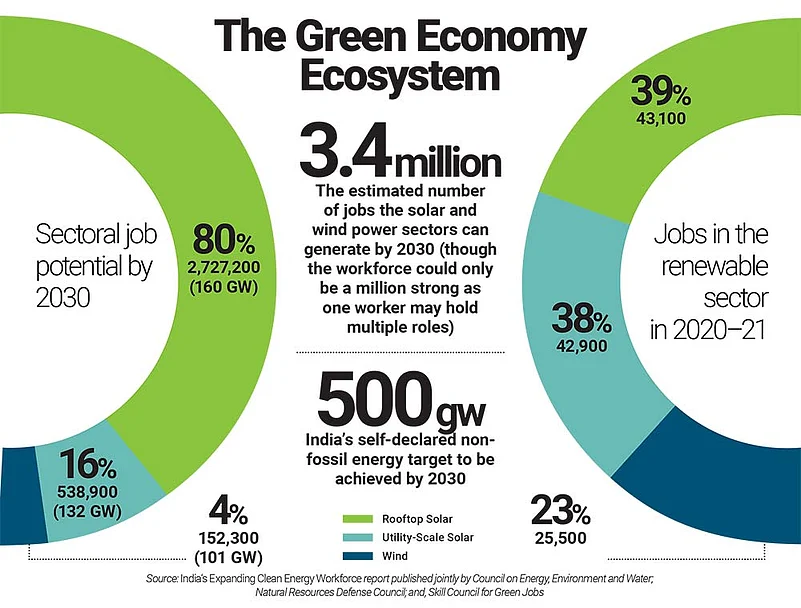

A just transition will require India to train the young members of families dependent on coal mining to join different sectors. One option could be to set up the solar and wind power plants, along with solar panel manufacturing units, in the affected states.

According to an analysis by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, India needs to scale up solar power to 5,600 GW by 2070 to meet its net-zero target. Currently, the country has a little under 58 GW of installed solar capacity, according to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy.

“Solar power will increasingly face land issues. It does not generate as many jobs as you see in the coal economy. Given the just transition challenge, India will need to ensure that some of the socio-economic benefits of solar go to coal-dependent states. Currently, all the new projects, and therefore jobs in renewable energy, are going to western and southern states,” says Pai.

Currently, out of the 58 GW installed solar capacity, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Odisha and Madhya Pradesh, the coal-mining-dependent states, account for only 4 GW. In contrast, by the end of FY21, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh had around 21 GW of installed solar capacity. This shows that the richer states are already moving towards the future energy resources, helped by their better financial position along with support from the Central PSUs while coal economy states are unable to visualise a future without coal.

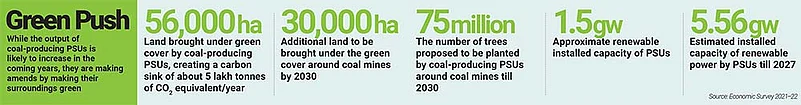

Going forward, it would be imperative for Central PSUs like National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC), CIL, Oil and Natural Gas Corporation and other energy-based companies to divert a lion’s share of their investments to states that will be the most affected due to transitioning into the renewable energy economy. Northern Coalfields Limited (NCL), a subsidiary of CIL, and NTPC, the country’s largest power producer, have already tied up to develop a 50 MW solar plant in NCL’s Nigahi coal mine in Madhya Pradesh’s Singrauli district.

So far, the Centre has provided subsidy worth Rs 3 lakh crore since 2014 on coal. It must further dig into its coffers by, perhaps, reprioritising the coal subsidies. The government will have to reprioritise its subsidies towards the coal-bearing states, says Shravan Sampath, CEO, Oakridge Energy. “Most of the coal-bearing areas in India have a good rail and highway connectivity that was created for coal transportation. These areas could be notified as industrial zones for value-added industries in related areas, such as steel, cement or aluminium,” he adds.

Apart from the allied sectors, the Centre will also need to give preferential treatment in resource allocation to the affected states in the coming decades if it is serious about the justness of the transition process.

Righting a Wrong

Historically, the Indian policymaking has favoured the western and southern states. The freight equalisation policy in 1952 played an important role in incentivising industrialists to set up industries in coastal states. Under the policy, the Centre subsidised the transportation of minerals to a factory set up anywhere in the country. The policy disincentivised setting up of industries in the mineral-rich states, because the Centre was paying for the cost of raw materials and the industrialists wanted to reap the benefits of being closer to the sea for the ease of import of other raw materials and export of end products.

In 2017, then president Pranab Mukherjee held the freight equalisation policy responsible for the extreme poverty of the eastern Indian states. “[D]espite having mineral resources and fertile land, Bihar, and now Jharkhand, too, could not make the desired progress,” Mukherjee had said at an event of the Asian Development Research Institute.

Though the policy was withdrawn in the 1990s, the damage was already done to the economies of these states, as private capital had already been invested in west and south India, where electricity was available through the national grid along with better infrastructure that was created in the first four decades after the independence.

Today, a large number of people living in eastern and central states are either working in low-end jobs in the mining industry or are migrants working in difficult conditions and for low wages in industrialised states like Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Karnataka and Maharashtra.

Ironically, it was the mining of coal over the last 75 years of the independent India that left these states poor, and now, if these mines are closed without arranging for a just transition of the dependent population, it is likely to cause more devastation.

Many modern-day economists and policymakers blame the governments of eastern states for the extreme poverty that exists in these states, but when there is no industry in a region, it is not possible for any government to do much, says Mahendra Kumar Singh, who teaches political science at Deendayal Upadhyay Gorakhpur University. “As a nation, we need to take a collective decision to set up large-scale factories in the eastern region of India. This is where India’s most poor population lives. How we manage the transition of east Indian states in the coming years will decide whether we become a developed nation or not,” says Singh.

A major challenge that the coal-dependent states will face in future is about the management of their borrowings. With decline in revenue from coal mining, the states will struggle to keep their fiscal deficit under control. States that have lost their coal assets and revenue accrual from them are likely to face credit rating actions from international agencies, which will increase their cost of borrowing. “This will curtail borrowings to the extent that costs may rise due to an adverse fiscal position,” says Tandon. She stresses the need for the Centre and the states to jointly manage the cost of transition, like any other development goal, be it loss of revenue or cost of support to livelihoods.

Tandon suggests modification in the way tax devolution is decided under the finance commission formula. “The devolution of fiscal resources, at the moment, is based on income and demographics. Energy transition will assume importance, and it is widely known that its impact will vary spatially. As the subsequent finance commissions consider the devolution rule, it may be useful to incorporate resource dependence in the rules for devolution, especially since revenues from fossil-fuel minerals will decline,” she says.

Talking about the freight equalisation policy, Tandon says, “The policy was an unsuccessful attempt at achieving balanced regional development. With the focus on just transition, we are revisiting the issue of balanced regional development but are asking how states rich in fossil fuel minerals and industries dependent on fossil fuels will regenerate their economies.”

It is during times like these when the fate of a nation and its people are written for the next 100 years. Seventy years ago, when India chose the freight equalisation policy without compensating the resource-rich states, it burdened their entire populace for three generations. Today, while leading climate negotiations, the government has a tall task to ensure that those people are not made to carry the burden for another century.

***

We Will Introduce Transition Tax On Coal: Hemant Soren

Being the largest coal-bearing state, a lot is at stake in Jharkhand due to India’s COP26 commitment. Chief Minister Hemant Soren says that his government is working on a contingency plan. Edited excerpts:

Do you think the shift to renewable energy will create an employment crisis in Jharkhand given its massive coal economy?

Yes, there is no denying the fact that there will be an employment crisis for the people working in coal fields in various capacities in Jharkhand. Out of all of them, mine workers will be affected the most, because of the closure of mines owing to transition from coal to renewable energy sources. Although there is no immediate crisis, plans for proper rehabilitation and reskilling are being conceptualised.

Has the state government raised the issue with the Centre? Is there any long term package that your state is planning to seek from the Centre for just transition?

As a part of our plan to work out resources for rehabilitation, my government aims to introduce a transition tax on coal. The money collected from this tax will be utilised by the state to provide alternative livelihood opportunities to people impacted because of the transition. Moreover, the current focus is also around how to utilise the District Mineral Foundation Trust fund to develop the capabilities of the people in the mining regions, so that they are able to find alternative sustainable livelihood opportunities.

What are your plans for rehabilitation?

My government is laying emphasis on developing tourism in the state. We have realised that mining tourism has a lot of potential, as it attracts tourists in hordes. We are planning to employ the workers who will become jobless in the tourism sector in the future. Besides this, green jobs in the field of renewable energy too has potential. That is another area where the capabilities of the people need to be built to meet the future demand.

—Jeevan Prakash Sharma